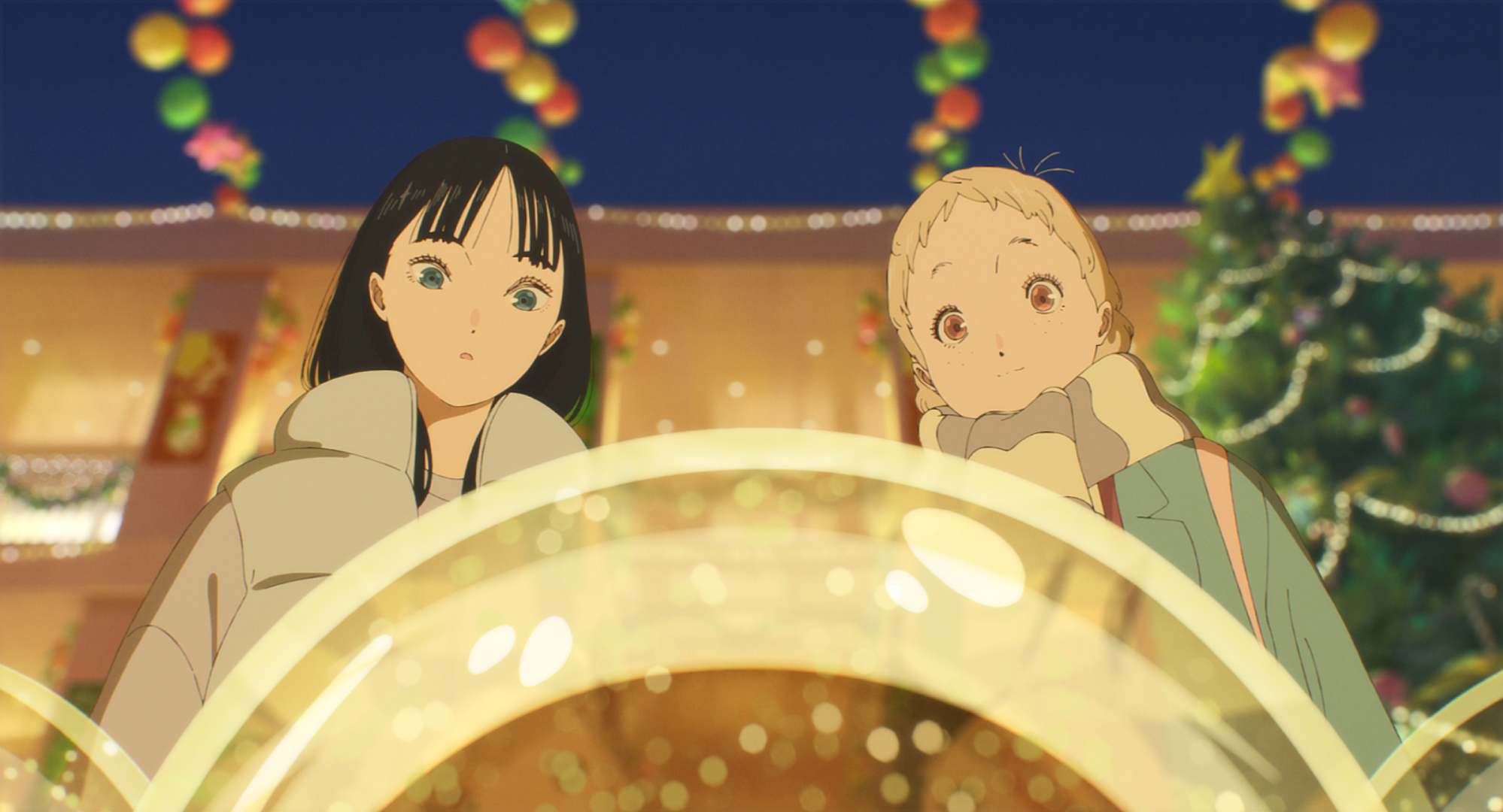

“If I could see my own colour, what kind of colour would it be?” the heroine of Naoko Yamada’s The Colors Within (きみの色, Kimi no Iro) asks herself. Yet there’s a curious pun in the film’s Japanese title in that the word “kimi” simply means “you” but it’s also the name of another girl by whom Totsuko (Sayu Suzukawa) is captivated though she doesn’t quite have the ability to articulate her feelings beyond the fact she feels “all sparkly inside”.

In any case, Totsuko has the ability to see people as colours but largely keeps it to herself in fear that people will think she’s “weird”. Totsuko does indeed appear to be slightly otherworldly, though no one really seems to reject her for her ethereality save perhaps one classmate who describes her as that girl who sits in the chapel on her own all the time. What she’s mostly doing in there is reciting the serenity prayer to find “peace of mind,” and talking to the cool nun at her Catholic boarding school, Sister Hiyoko (Yui Aragaki), who tries probe gently into whatever it is that’s bothering Totsuko but equally avoiding pressuring her reveal anything before she’s ready. Then again, Totsuko may not quite know what it is that’s making her feel uneasy even if she remains upbeat and cheerful with a childlike sense of fun and innocence.

This quality of joyfulness is directly contrasted with the intense melancholy of Kimi (Akari Takaishi) with whom Totsuko becomes fascinated after catching sight of her “beautiful” and “clear” colours. When Kimi disappears from the school it’s rumoured she talked back to a teacher or that they found out she had a boyfriend, but it seems a Catholic education just isn’t a good fit for Kimi so she decided to drop out. Like Totsuko, Kimi has a secret but hers is that she can’t bring herself to tell her grandmother, who attended the same school and is over the moon about her going there, that it isn’t working out for her. What with it being a Catholic school, there’s also the implication that Kimi and also Totsuko may be struggling to define themselves within a repressive environment and reconcile their differences in the intense fear of not only being rejected by their community but damned to hell.

After Totsuko checks every bookshop in town because someone said they saw Kimi working in one, she accidentally starts a band with her and a boy who just happened to wander in, Rui (Taisei Kido). Rui also has a secret which is his love of music which he fears conflicts with his responsibility of taking over the family medical practice. He isn’t exactly sure he wants this future that’s been forced on him and prevents him from following his dreams. In fact, none of the teens really wants the kind of life their parents wanted for them but they aren’t yet certain of the kinds of lives they do want or really who they are which is why Totsuko is still unable to see her own colour despite clearly discerning everyone else’s.

Through making music together, they discover new ways of expressing themselves and with it growing self-acceptance that allows them to be honest with themselves and others about who they are and what they want. Music in itself becomes an act of holy communion with the universe, a pure communication of one soul to another much like Totsuko’s synaesthetic ability to see people as colours. Even Sister Hiyoko insists that any song that is about goodness, beauty, truth or indeed suffering is itself a hymn and in the end Totsuko’s song is about all those things. Her joy, Kimi’s sadness, and Rui’s confusion coming together in a harmonised symphony as a consequence of “sharing secrets and feelings of love”. This sense of delicacy extends to the animation itself which has a watery, ethereal quality. Produced by Science Saru, this is the first of Yamada’s films not based on existing material and is underpinned by a tremendous empathy for its anxious adolescents as well as their uncertain adults along with a true sense of wonder for a world of colour and light hidden from most but visible to the ever cheerful Totsuko content to dance through life for the pure joy of it even if as she says she wasn’t very good.

The Colors Within screened as part of this year’s BFI London Film Festival and is released in UK cinemas on 31st January courtesy of All the Anime.

Trailer (Japanese with English subtitles)

Images: © 2024 “THE COLORS WITHIN” FILM PARTNERS

Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre.

Japanese cinema has its fare share of ghosts. From Ugetsu to Ringu, scorned women have emerged from wells and creepy, fog hidden mansions bearing grudges since time immemorial but departed spirits have generally had very little positive to offer in their post-mortal lives. Twilight: Saga in Sasara (トワイライト ささらさや, Twilight Sasara Saya) is an oddity in more ways than one – firstly in its recently deceased narrator’s comic approach to his sad life story, and secondly in its partial rejection of the tearjerking melodrama usually common to its genre. Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint.

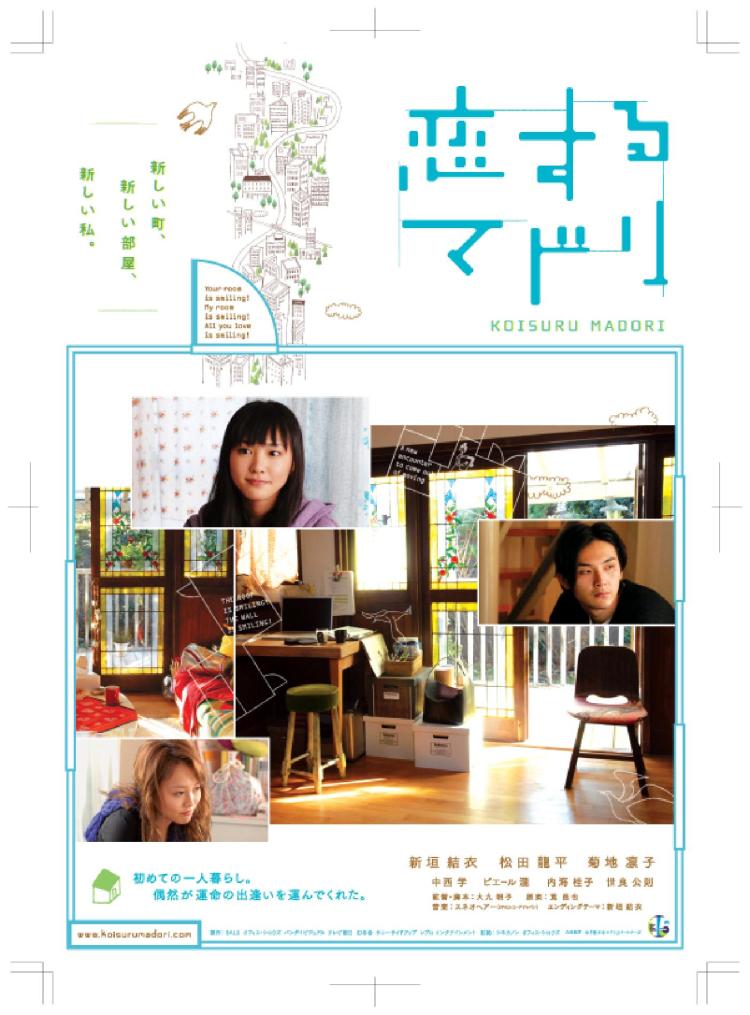

Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint.