Can a curse end up being “real” just because people believe in it? Unlike many of his other crime films which were adapted from the novels of Seicho Matsumoto, Yoshitaro Nomura’s The Village of the Eight Gravestones (八つ墓村, Yatsuhaka-mura) edges towards the idea that the curse at its centre is real in a more literal sense with grimly grinning samurai standing on their hilltop and rejoicing in the fulfilment of the 400-year campaign of vengeance, but also hints at a toxic legacy of enmity and warfare along with a karmic sensibility found in many of Seishi Yokomizo’s other mysteries in which a noble family must account for the way it gained its riches.

In this case, the Tajimi family which now owns most of the village became prosperous after betraying a band of eight displaced samurai during the Sengoku era. Fleeing the battlefield in defeat, the samurai had originally frightened the villagers when they came down off the mountain but were in actuality non-threatening, simply settling down to a life of farming and peaceful co-existence. But some members of the community became greedy and accepted the promises of riches from a rival clan for the service of eliminating the eight samurai. Cruelly inviting them to the local festival in what seemed like a moment of acceptance as members of the village, they betrayed them killing some by poison and others by the sword.

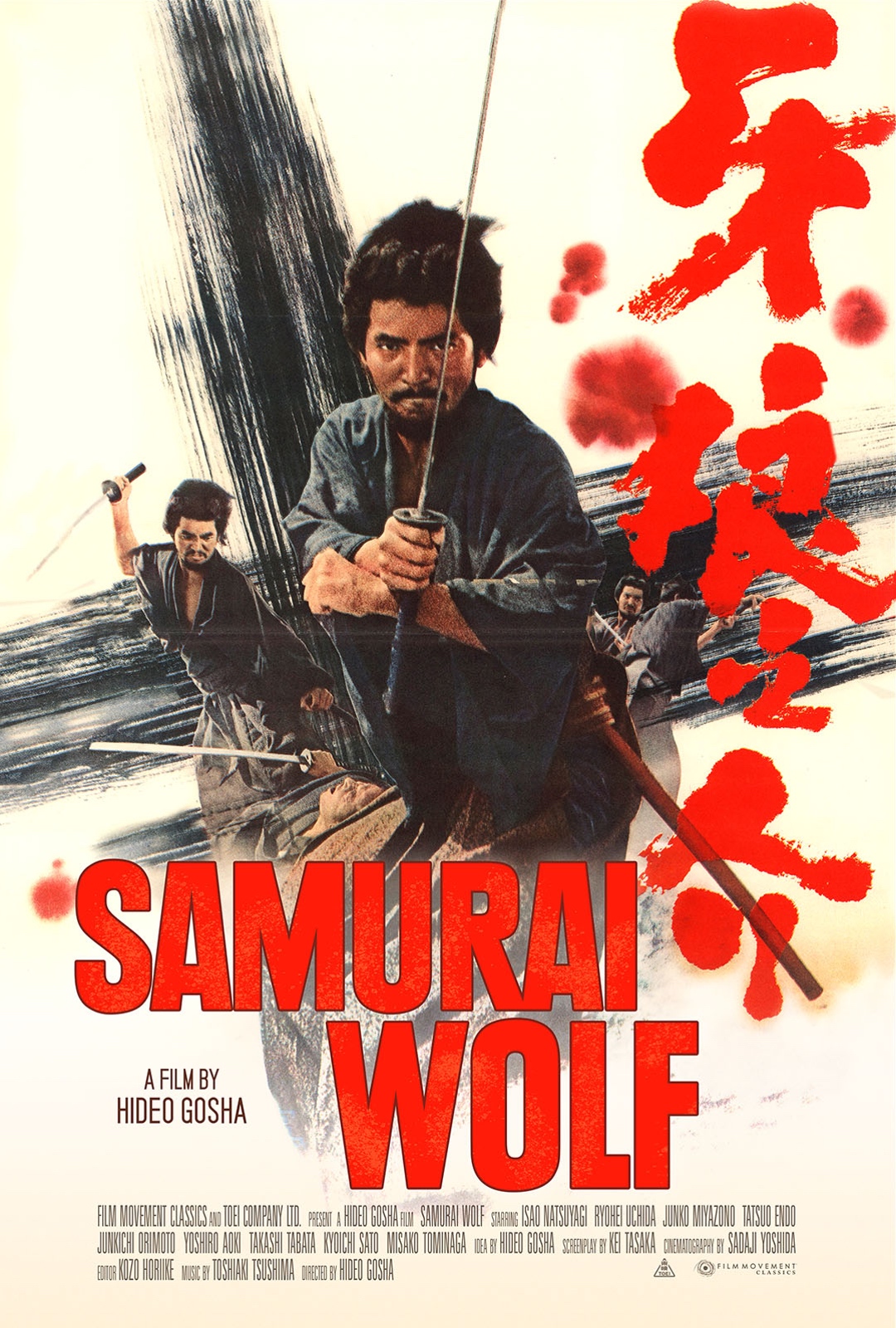

Now, hundreds of years later, the Tajimi family is on the verge of extinction with the eldest daughter unable to bear children and the oldest son bedridden and soon to die which explains why they’re keen to track down long lost grandson Tatsuya Terada (Kenichi Hagiwara) who was presumably adopted by his stepfather and bears his name after his now deceased mother Teruko left the family to escape her abusive relationship with half-mad husband Yozo (Tsutomu Yamazaki). Surprisingly, it’s his maternal grandfather Ushimatsu Igawa (Yoshi Kato), who comes looking for him only to drop dead as soon as they meet of apparently strychnine poisoning in the first of several murders that all echo the ancestral curse placed upon the Tajimi family by samurai leader Yoshitaka Amako (Isao Natsuyagi) as he died.

Like many of Nomura’s films this too features a journey only this one is in a sense into the past as Tatsuya ventures to the rural heart of Japan hoping to see his mother’s birthplace and satiate his curiosity about his birth father. What he discovers there is obviously a lot of what seems like unfounded local superstition along with a degree of unpleasant stigmatisation as he’s immediately accosted by a shamaness who calls him a murderer to his face for his connections with the Tajimis to whom he feels himself a stranger, and then is later blamed for all the weird goings on which only began after he arrived. The film uproots itself from the original 1948 setting to the present day which perhaps lessens the impact of its central theme about the legacy of violence and betrayal that is stoked by war and enmity along with the destructive capacity of human greed that encourages some to betray others for their own advancement only to discover that success founded on human sacrifice will never get you very far.

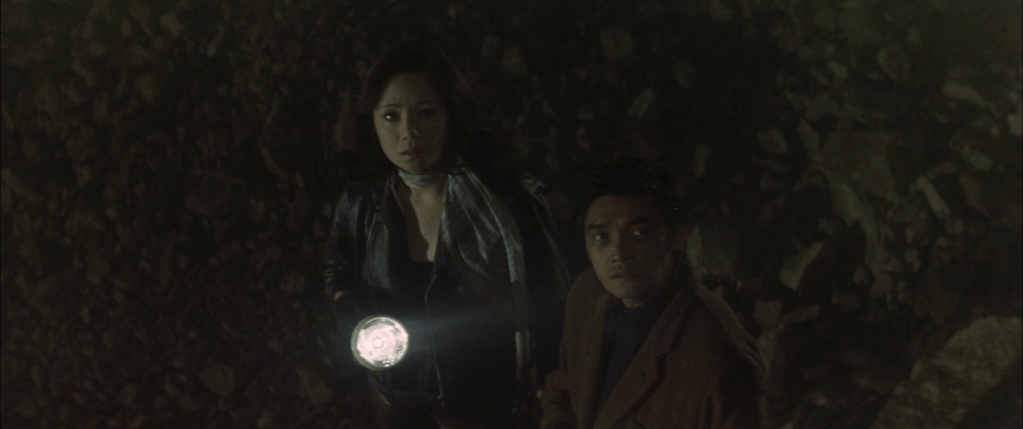

Ironically in a more real world sense, it turns out to be greed that motivates these present crimes with the villain hoping to usurp the Tajimi family fortune and utilising the curse as a means to do so. Much of the action takes place in a network of underground caves filled with glowing green lakes where the villain eventually takes on demonic proportions, face ghostly white with yellowish eyes and a crazed expression that echoes those of the samurai as they died. Nomura hints at the sense of ancient dread in this very old place while also surprisingly bloody in his flashbacks which feature scenes of shocking violence including severed heads one of which seems to lick its lips and stare intently even while on display. This being a Kindaichi (Kiyoshi Atsumi) mystery, the famous detective does indeed appear though remains a background presence quietly solving the crime behind the scenes while Tatsuya searches for the key to his own history and an escape from this legacy of violence and destruction in reclaiming his own identity.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

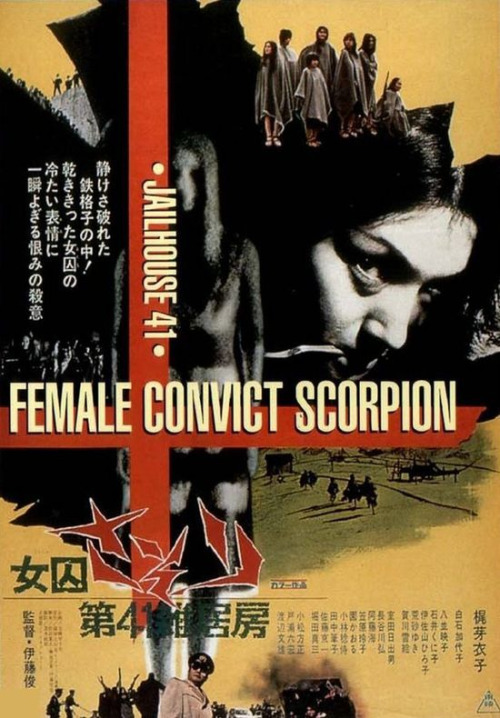

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of