“Two bad guys will catch the worst man” according to irritated gangster Jang Dong-su (Ma Dong-seok) in Lee Won-tae’s The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil (악인전, Akinjeon). He doesn’t quite know how right he is, even as he forms an unlikely alliance with a maverick cop himself highly irritated because his lazy colleagues won’t listen to his theory that a spate of unsolved murders are the work of a serial killer. More alike than they’d care to admit, the two “bad guys” team up to do what they have to do in order to make the killing stop but at what price?

“Two bad guys will catch the worst man” according to irritated gangster Jang Dong-su (Ma Dong-seok) in Lee Won-tae’s The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil (악인전, Akinjeon). He doesn’t quite know how right he is, even as he forms an unlikely alliance with a maverick cop himself highly irritated because his lazy colleagues won’t listen to his theory that a spate of unsolved murders are the work of a serial killer. More alike than they’d care to admit, the two “bad guys” team up to do what they have to do in order to make the killing stop but at what price?

A vicious killer (Kim Sung-kyu) has developed a habit of rear-ending solo drivers on lonely roads, stabbing them repeatedly and then leaving them for dead. Maverick cop Tae-seok (Kim Mu-yeol) has become convinced that the killings were carried out by the same perpetrator and that they have not yet been identified as a “serial killer” partly because the crimes took place in different districts and there is insufficient co-operation between precincts, and partly because his colleagues think serial killers are something you see in American movies. His superiors just want to close cases, they aren’t particularly concerned with upholding justice or protecting the innocent and so Tae-seok starts thinking outside of the box when he hears that the killer’s latest target was none other than top mob boss Jang Dong-su.

Dong-su got rear-ended after running an errand to have a word with a wayward underling, Hur (Yoo Jae-myung), who has forgotten his place. The killer made a serious mistake going after Dong-su who is a big, handy kind of guy and therefore manages to fend him off, even wounding him in the shoulder despite being badly injured himself. Though the obvious conclusion is that Hur sent someone after him, Dong-su is unconvinced seeing as he had never seen his assailant before and is pretty sure he’s not a member of the gangster underworld. Still, he’s very annoying because a gangster only has power in being respected and right now Dong-su looks a fool. If he wants to get his “professional” life back on track, he needs to get his revenge but to do that he’ll have to cross the floor and work with law enforcement, temporarily teaming up with rogue cop Tae-seok whose heart is in the right place even if he’s not averse to bending the rules.

One of the things which most bothers Tae-seok about amoral killer “K” is that, unlike most serial killers, he kills indiscriminately and purely for pleasure. He has no “type” and generally goes up against those most likely to fight back, unlike your average pattern killer who targets the vulnerable. Like Tae-seok and Dong-su, he is however quite annoyed – this time because someone has “framed” him for a murder he didn’t commit in order to further their own ends. Hugely overconfident and cooly psychopathic, he sits in the dock and asks what makes his crimes different than the state’s if the state is fixing to execute him without proper evidence. Pointedly looking at law enforcement, he affirms that the real villains are those who commit crime with kind faces (say what you like, but at least K looks the part).

When it comes to Tae-seok he might have a point. Conspiring with Dong-su to “kill him with law”, Tae-seok gleefully manipulates the system while giving Dong-su tacit permission to take his revenge as long as “justice” has been properly served. K doesn’t believe in anything, Tae-seok believes in a particular kind of “justice” if not quite in the law, while Dong-su mourns the sense of self-belief that allows you to rule the roost as an all powerful gangster. The three men are a perfect storm, each angry, each resentful, each vowing a particular kind of revenge against the forces which constrain them be they corrupt and lazy superiors, gangsterland disrespect, or the “injustice” of being accused of a crime you did not commit but not being properly credited for the ones you did. Bathed in a garish neon, Lee’s anti-buddy-cop drama embraces its noirish sense of fractured morality with barely suppressed glee as its similarly conflicted heroes pursue their violent destinies, true to their own but dragged to hell all the same.

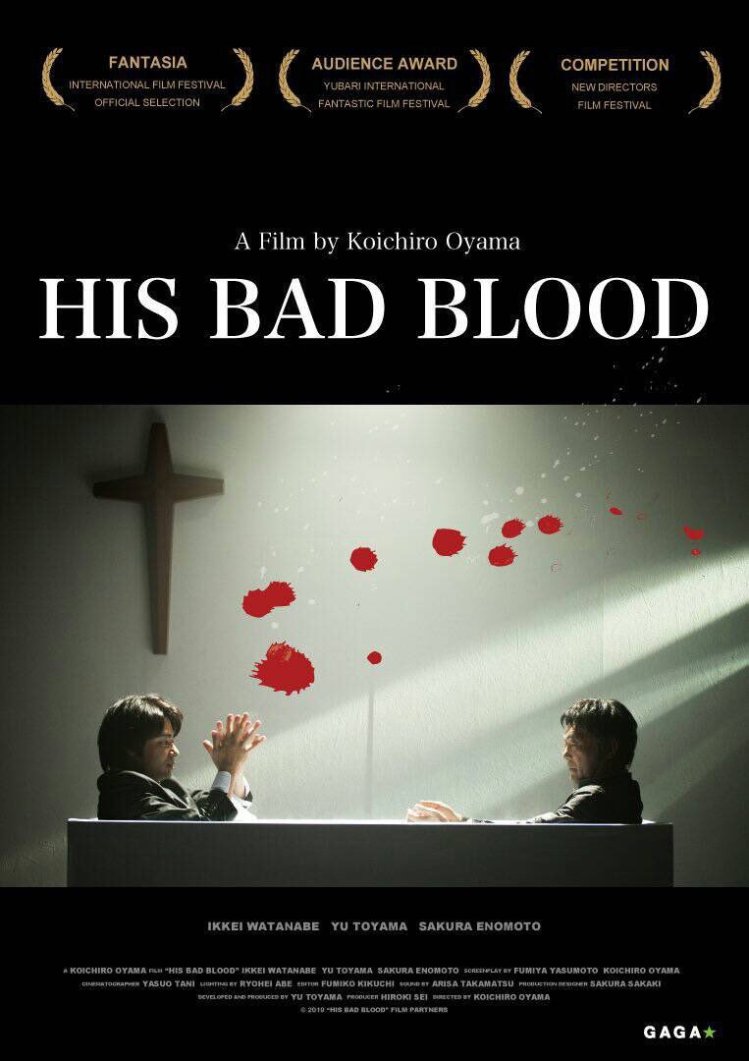

The Gangster, The Cop, The Devil was screened as part of the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

“Maybe it would be better if I just disappeared rather than physically be here but feel invisible all the time” the lonely heroine of Dwein Ruedas Baltazar’s Ode to Nothing (Oda sa wala) sadly laments to her only source of comfort, a semi-embalmed corpse. A melancholy meditation on the living death that is existential loneliness, Ode to Nothing takes its alienated heroine on a journey of hope and disappointment as she rediscovers a sense of joy in living only through befriending death.

“Maybe it would be better if I just disappeared rather than physically be here but feel invisible all the time” the lonely heroine of Dwein Ruedas Baltazar’s Ode to Nothing (Oda sa wala) sadly laments to her only source of comfort, a semi-embalmed corpse. A melancholy meditation on the living death that is existential loneliness, Ode to Nothing takes its alienated heroine on a journey of hope and disappointment as she rediscovers a sense of joy in living only through befriending death.