“Britain has reassured the people that it will not give up Hong Kong,” according to a radio broadcast at the beginning of Leong Po-Chih’s Hong Kong 1941 (等待黎明). The words have a kind of irony to them and not only because Britain did abandon the people following the Japanese invasion, but because the film was released on the eve of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in which it said something quite similar.

But then again, the opening scenes are themselves quite critical of British rule as they, on the one hand, insist they aren’t going anywhere and, on the other, start evacuating women and children to “safer” areas of the commonwealth such as Australia. Out of work actor Fei (Chow Yun-fat) fled the Japanese incursion on the Mainland and came to Hong Kong, but now tries to stowaway abroad a boat going to Australia. He’s caught by a little British girl who speaks fluent Cantonese yet refers to him as her “slave” and insists that he “kowtow to me, now.” But then the girl suddenly adopts the persona of the Empress Dowager Cixi and demands the same. Fei makes the first of his many jumps into the water around Hong Kong, as if only in this liminal space can he be free. Anticipating the wave of migration occurring before and after the Handover, and also that of the present day, he and his friends Keung (Alexander Man Chi-leung) and Nam (Cecilia Yip Tung) set their sights on leaving to find Gold Mountain in Australia or America.

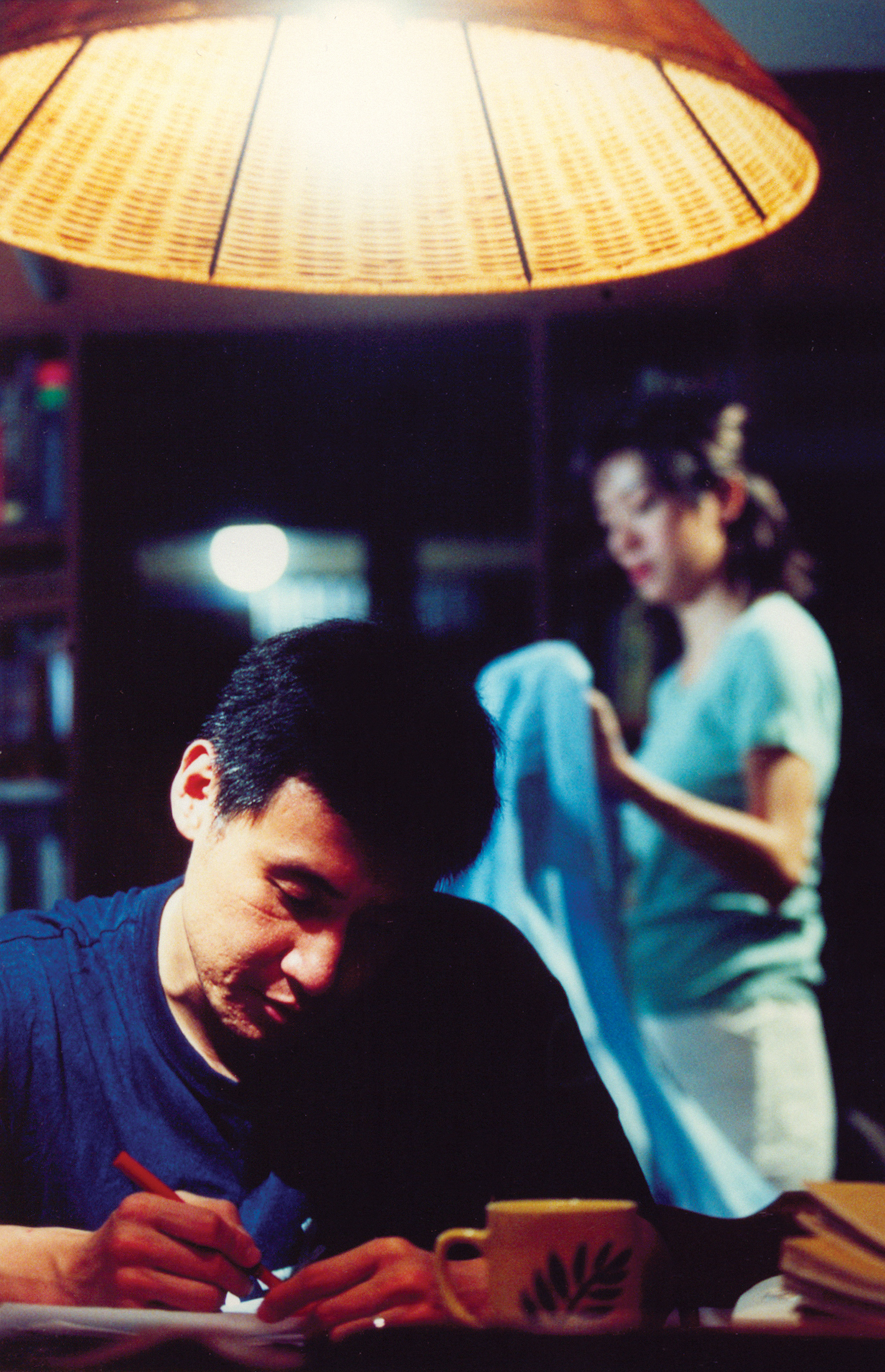

But they’re one day too late because the date of their departure is that the Japanese arrive in Hong Kong. Their haste to leave was in part caused by the fact that Nam’s father, Ha Chung-sun (Shih Kien), was trying to force her to go through with an arranged marriage her prospective groom didn’t want either. Nam is never really free as, as she points out, even after her father relents and allows Keung to marry her after she is raped by a police officer emboldened by the chaos and therefore worthless to him as currency, Keung never actually asked her and she’s in effect forced into a marriage with him instead. In fact, she returns to the shrine Keung lives in two find the two men constructing her marital bed for her with the double helix symbol of happiness already placed above it in an ironic expression of patriarchal oppression.

Indeed, her position is more precarious than either of the men and we see other families roughly cutting their daughters’ long hair to make them look like boys in fear of a rapacious Japanese army. But it largely turns out that it wasn’t so much the Japanese they needed to be worried about as the local population, experiencing a temporary limbo in which the social order has been suspended. Police officer Fa Wing (Paul Chun) who had acted as a lackey for Ha Chung-sun while constantly eying up Nam leads a gang of looters to Ha’s house to take their own revenge against his capitalistic oppression of them. Ha had largely made his money through rice profiteering and exploiting the local workforce. Recent layoffs at the warehouse had led to a labour riot, while Keung and his friends had been running a sideline skimming sacks of rice to sell on the black market.

Ha and his henchmen anxiously await the arrival of the Japanese hoping that they will protect them from retribution, but the Japanese do not arrive fast enough. When they do, Ha collaborates and attempts to ingratiate himself with the Japanese officer in charge of the colony who once again takes a liking to Nam. General Kanezawa (Stuart Ong) also uses their poverty to starve them into submission, promising rice to anyone who will come and sing with him. The song he chooses is “Shina no Yoru” by Li Hsiang-lan, whom he describes as “their very own”, yet was actually a Japanese woman, Yoshiko Yamaguchi, groomed for stardom in Manchuria and marketed a Chinese star in propaganda films. Another song of hers, Ieraishan, can be heard earlier on the soundtrack as if heralding Japanese arrival.

Though Nam tries to resist, Fei raises the trio’s arms in a cry of “banzai” in a moment of ostensible collaboration designed to buy them temporary safety. His philosophy and that of many others is to take the rice and deal with the rest later, which Fei does by becoming an enforcement officer with the Japanese to get papers that will allow all of them leave. He uses his position to help a gang of Mainlanders who are resisting the Japanese, and are, in fact, the last ones to stay behind and defend the colony, as well as well as save Keung when his attempt to rescue two friends who have been sold out for forced labour on another Japanese-controlled island by a local gangster backfires and he’s captured himself.

Ironically enough, Fei had been the first one to try to leave and described himself as “selfish” after jumping back into the water to return to Nam and Keung who didn’t make the boat on time because they were trying to save a local eccentric everyone calls “emperor” played by the director himself. Fei is quite obviously in love with Nam, and she gradually falls for him in return though symbolically wedded to Keung, if not in the legal sense. Again, she has no say over her romantic future which is sorted out between the two men with Fei abiding to a code of honour in continuing to protect the relationship between Keung and Nam. Perhaps this echoes the way in which the Hong Kong people of 1941 or 1984 have little say in their future either as their fate is decided by two distant powers. Nevertheless, it leaves Keung feeling awkward and inadequate, realising that Nam likely prefers the smart and dynamic Fei over his constant failures and inability to protect her, though he is never jealous or resentful towards him only knowing that he is continually indebted. Yet it’s Nam who eventually strikes back for Hong Kong and for her own freedom while Fei looks on as children in the street play at beheadings as if they were Japanese soldiers. She embodies the spirit of Hong and carries it with her, and as the Chinese title of the film suggests, waits for a new dawn while accepting that just like old memories it will be replaced by what is to come. She speaks from a perspective that is both historical and uncertain, mourning the past while fearful of the future, but all the while continuing to live as one new dawn replaces another.

Hong Kong 1941 screened as part of this year’s Focus Hong Kong.

Trailer