Cute characters are ubiquitous in Japan and though many may associate them with merchandising aimed at small children, a more recent trend has expressly targeted dejected adults perhaps longing for an escape into a kinder, more innocent world. San-X has been at the forefront of this trend with its hugely popular merchandising lines often featuring characters who just want to take things easy and enjoy life such as the lazy bear Rilakkuma or the roly-poly Tarepanda. Featuring an entire cast of neurotic characters, Sumikkogurashi has been one of the studio’s most successful collections appearing on everything from stationery items to cookware and clothing.

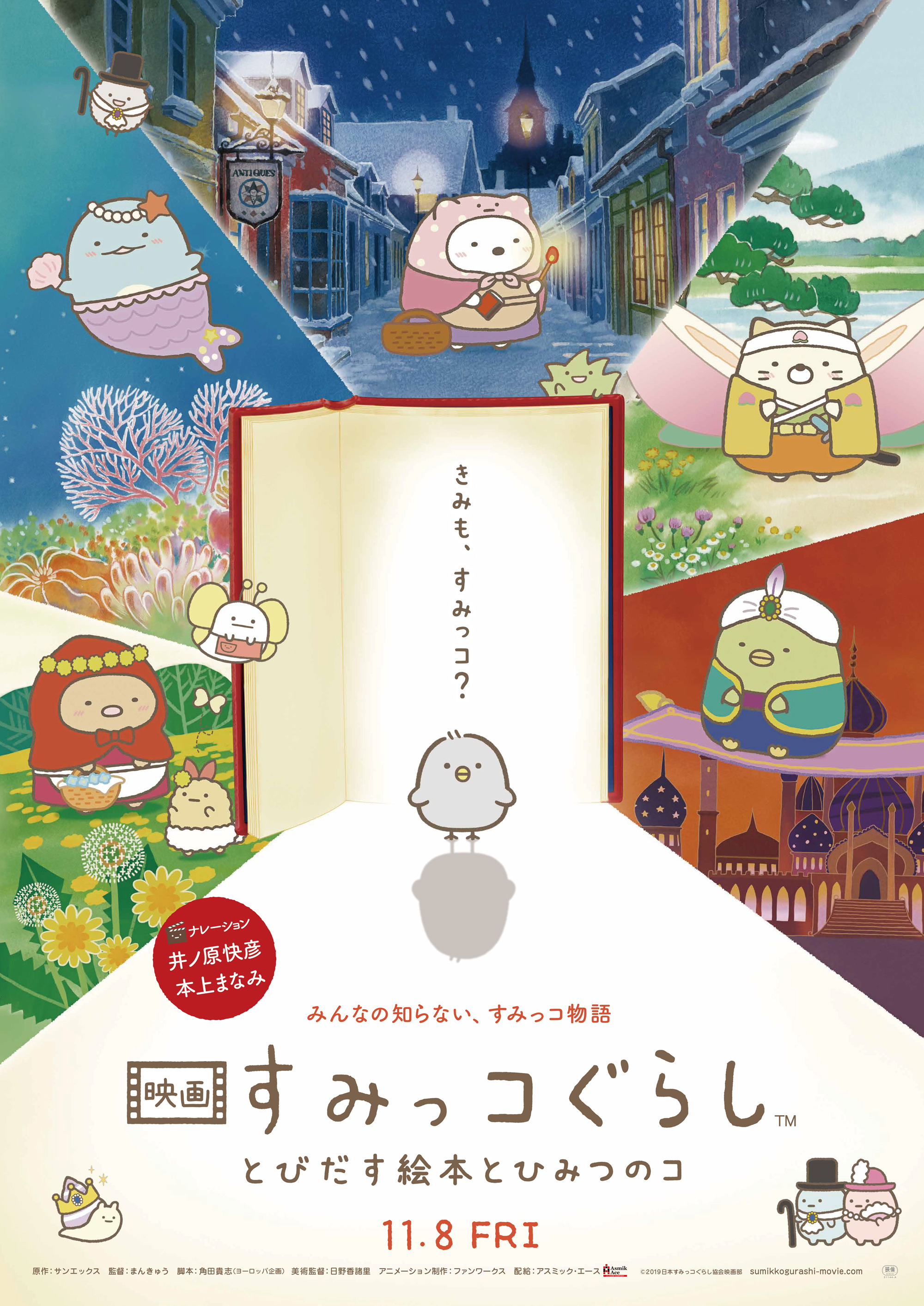

Sumikkogurashi: Good To Be In The Corner (映画 すみっコぐらし とびだす絵本とひみつのコ, Eiga Sumikkogurashi: Tobidasu Ehon to Himitsu no Ko) is the franchise’s first animated movie and at just over an hour long is aimed squarely not at the regular adult audience but at small children (or perhaps the small children of the same overly anxious adults), taking inspiration from various international fairytales as the guys go on an improbable adventure to help a lost little duckling trapped inside a book. For those not already familiar with the world of Sumikkogurashi, the picture book-style narrators (Yoshihiko Inohara & Manami Honjo) introduce each of the characters who never speak themselves but communicate with each other through onscreen text mimicking that which appears on their character goods later interpreted by the narrators. The central theme of the Sumikkogurashi franchise is that each of the characters is intensely neurotic and has retreated from the world in favour of the relative safety of the corner of the room where they find solidarity with other similarly troubled souls which include a polar bear afraid of the cold, a shy cat, the remnants of a tonkatsu cutlet too oily to finish and his shrimp tail buddy, a bunch of tapioca pearls left in a cup of bubble tea, and a green penguin who is confused about their identity wondering if they are actually a lost kappa.

It’s to Penguin? that the main drama belongs as he bonds with the lonely duckling who has come loose in a book of fairytales and wants to find out where they belong. Sucked into a pop-up book, the Sumikkogurashi guys find themselves taking on the roles of the main characters with shy cat Neko cast as fierce yet tiny warrior Momotaro, Shirokuma as The Little Match Girl forced to face the cold, Tonkatsu and Ebifurai no Shippo in Little Red Riding Hood, secret dinosaur Tokage as The Little Mermaid, and Penguin? thrown into the world of the Arabian Nights. Together they pledge to help Hiyokko, the lost duckling, find where they belong and hopefully some friends along the way facing their own fears as they go.

The irony is that the guys have to leave the corner and go on an adventure where they do not exactly overcome their fears but perhaps learn that there’s not so much to be afraid of, Neko for instance making friends with the scary demon who chases them to offer some “onigiri” (a minor pun) in return for the gift of dumplings rather than fighting him as in the Momotaro folktale, even if they obviously need to return to the corner in the end. The message is that no one is really alone, even if they’re lonely in the corner lots of other people are too and you can find comfort in all being lonely together. The simple, water colour-inspired animation style is a perfect match for the series’ “healing” aesthetic with its gentle humour and random puns appealing both to small children drawn in by the cuteness of the characters and jaded adults looking for a little comfort who are presumably the targets of the more sophisticated gags. A simple bedtime story, Sumikkogurashi: Good to Be in the Corner is filled with wholesome warmth that belies its neurotic premise as the guys find solace in friendship and kindness while contending with an unfamiliar and sometimes hostile world.

Sumikkogurashi: Good To Be In The Corner streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (no subtitles)