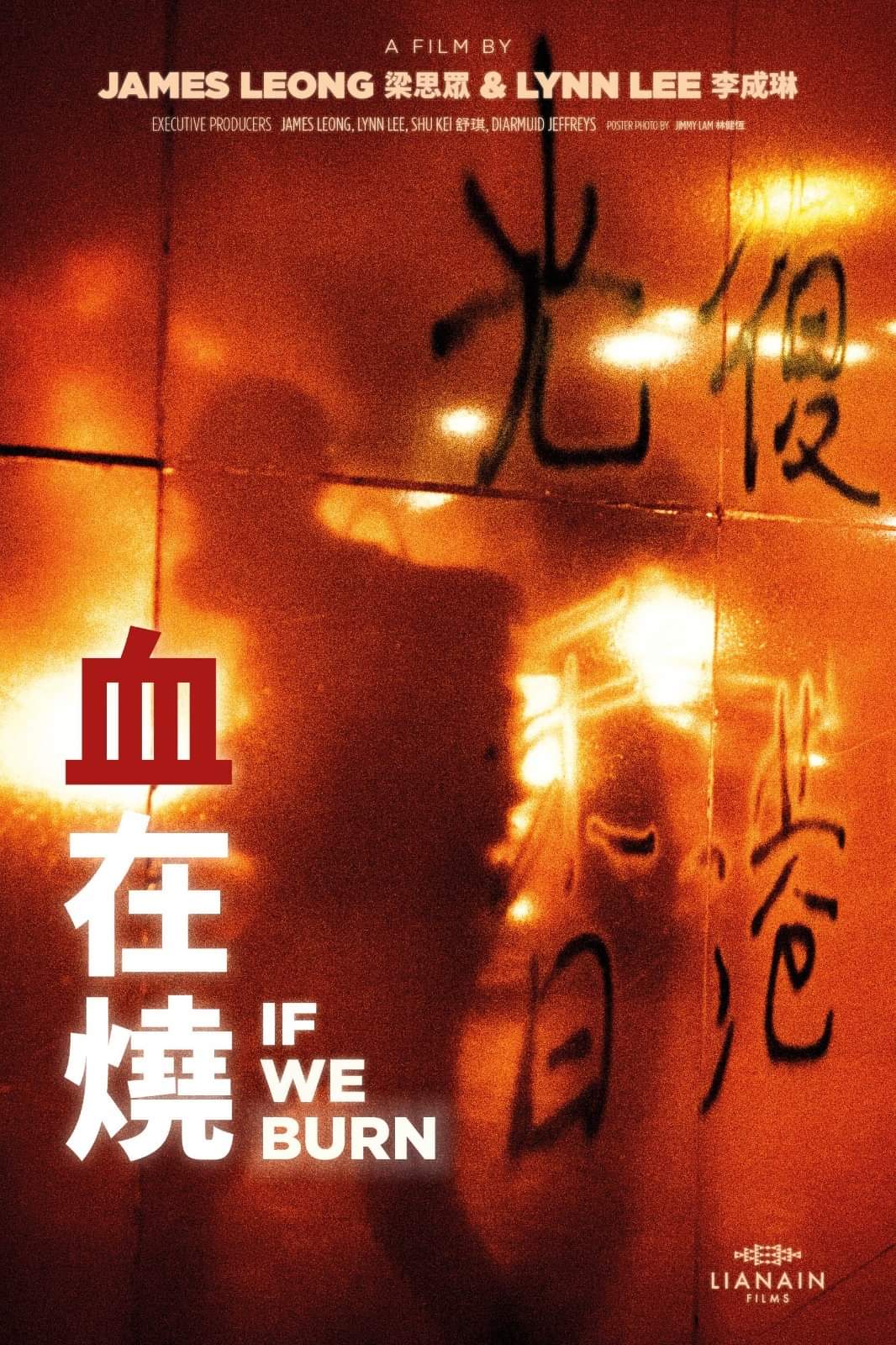

Clocking in at over four hours James Leong & Lynn Lee’s If We Burn (血在燒) provides the most comprehensive overview of the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement of any of the recent documentaries focussing on the events leading up to the passing of the Security Law in June 2020. Utilising professionally shot footage of the protests along with that captured by protestors via mobile phone, the film presents a tale of gradually escalating tensions provoked by increasing police violence and an expanding sense of hopeless desperation.

Focussing largely on a series of climactic events such as the storming of the Legislature, the Yuen Long and Prince Edward Station attacks, and the sieges of the Chinese University and Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the film posits police brutality as a deliberate tactic that developed into state terrorism designed to intimidate society into submission. In the talking heads segments which occupy the first half of the film, the filmmakers interview a journalist who was present at the Yuen Long attack and was herself beaten by the mysterious vigilantes who raided the station. In this and the attack at the Prince Edward station which followed, it was clear that the target was not solely protestors but the people of Hong Kong who were simply attempting to catch a train in order to go about their ordinary business and became victims of, in the case of the Prince Edward MTR passengers, state violence in an unwarranted police intervention. As the journalist explains, given such a threat to their safety it is not surprising that many were radicalised and that some who had previously been committed to peaceful protest resolved to fight fire with fire.

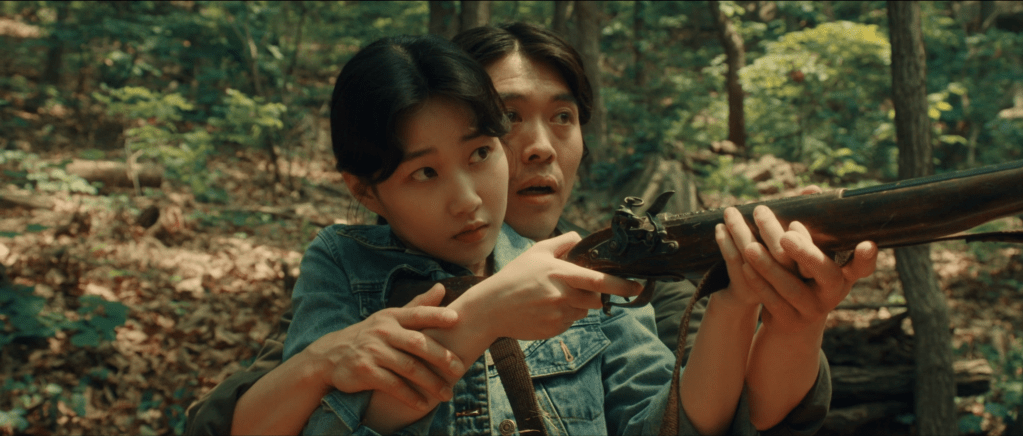

Some also regard the police action as a deliberate tactic, that in escalating violence the authorities attempt to provoke those protesting in order to justify even harder crackdowns. It’s also later revealed that police officers infiltrated the movement, dressing as protestors but suddenly attacking those around them giving rise to mistrust and paranoia. A lengthy sequence in which a mob at the airport protest catch a man they believe to be a Mainland police spy hints at the moral ambiguity of the protest movement as they argue with each other what to do with him while the man himself becomes a stand-in for the entirety of the violence inflicted so far. As tensions rise and duplicitous actions of the authorities increase, protestors begin to lose their sense of righteousness agreeing that there no longer is any line they will not cross to secure the freedom of Hong Kong.

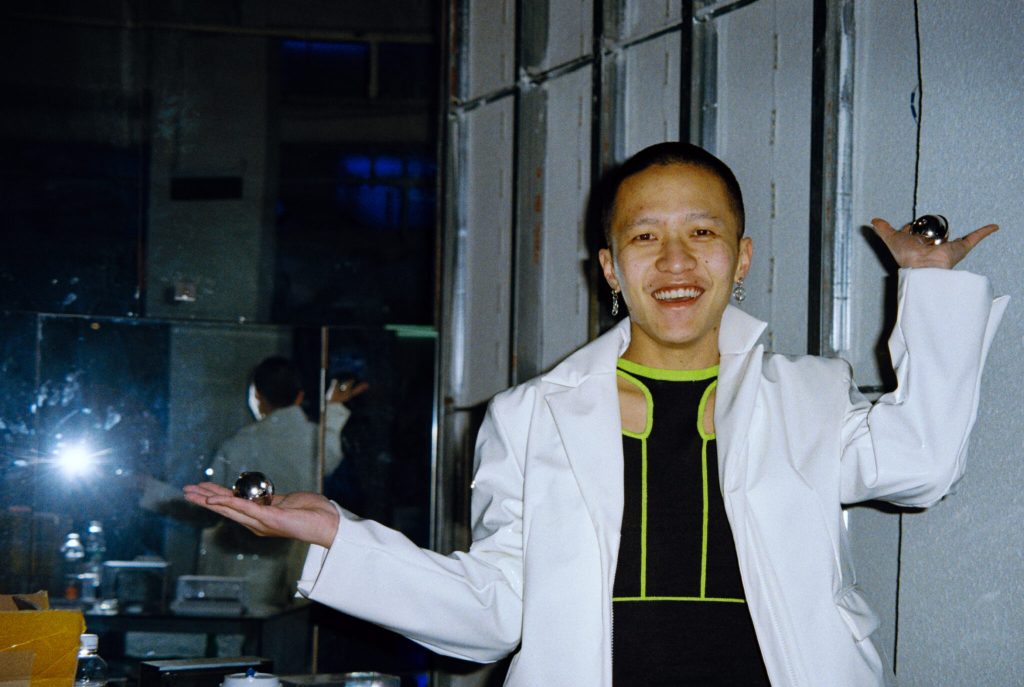

It’s clear that this period of instability has greatly affected the mental health particularly of younger protestors with many thrown into despondency and despair. During the university sieges, many state their intention to die and become martyrs while others talk of suicide and the toll the deaths of friends have already taken on them. During a rally in which older people offer thanks and support to the student protestors a young musician tearfully talks of how the the protest movement’s lack of success has exacerbated his depression and left him feeling hopeless with the only the solidarity of the people around him keeping him going.

What had begun as a simple request to reject the Extradition Law Amendment Bill soon turns into a series of five demands and finally towards a desire for independence among the more hardline of the protestors who are now so mistrustful of Mainland authoritarianism that they can never consent to living under it. The documentary ends with alarm bells still ringing and a post-apocalyptic vision of battlefield destruction in the quad of the Polytechnic University peppered with small fires and piles of rubble while police drag protestors away from the scene. Talking heads who still appear in masks and goggles with disguised voices look back on the effects of the protests and the various ways they are changing Hong Kong while a piece of onscreen text coldly explains that the Security Law was passed and many have since been arrested or fled into exile. Still, as the alarm bells ring over the closing scene featuring the graffiti that gives the film its title, the documentary seems to suggest that all not yet lost while flame of resistance continues unextinguished.

If We Burn screens at London’s Genesis Cinema 18th March as the Opening Gala of this year’s Hong Kong Film Festival UK.