An earnest young woman finds herself questioning her way of life after one of her charges is implicated in a spate of murders in Yoshiyuki Kishi’s social drama Prior Convictions (前科者, Zenkamono). As the double meaning of the English title implies, the issue is as much about preconceived notions and unfair judgements as it is about “crime”, its causes and legacies, while ultimately arguing for a more compassionate approach to law enforcement which prizes healing and rehabilitation over meaningless punishment.

Kayo (Kasumi Arimura) is what’s known as a volunteer probation officer which is to say that she assists those who’ve recently been released from prison to reintegrate into mainstream society so that they can live comfortable lives within the law. She is not however a civil servant and though making regular reports to an official probation officer has very little power and no pay for her work which can at times be difficult and emotionally draining especially considering that she also needs to work a regular job in a convenience store to support herself. In what seems like a very poor safeguarding decision, she meets most of her clients in her own home where she lives alone one of them even breaking in while she’s not there for an impromptu hotpot party.

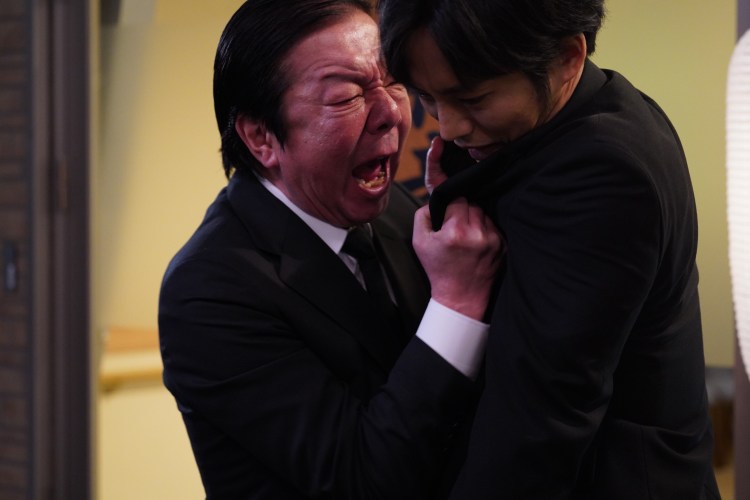

While she is exasperated by some of her charges such as a woman who can’t seem to stick to a regular job no matter how many she finds her, Kayo is incredibly proud of her work with Kudo (Go Morita), a quiet and soulful middle-aged man who was convicted of murder after stabbing a co-worker who had been bullying him so badly that he lost the hearing in one ear. Kudo had been struggling to reconcile himself to his crime, intensely worried that while unable to understand why he did it he might end up doing it again. When Kudo suddenly disappears after being linked to a series of suspicious deaths most assume the worst, but Kayo alone refuses to believe that Kudo could be the killer and is determined to find out what’s really going on if only to vindicate her conviction that her work is good and useful rather than naive and misguided as some including intense police officer Takimoto (Hayato Isomura) seem to see it.

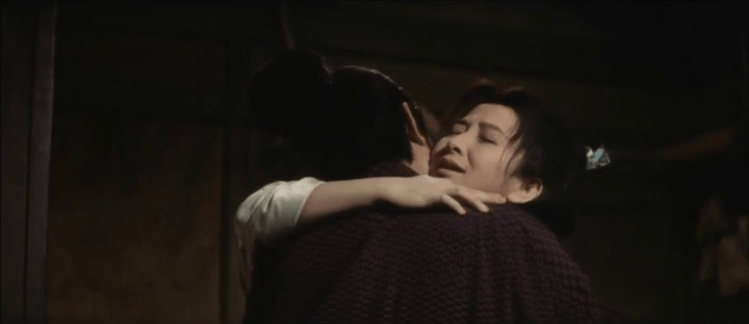

As Kayo later reveals she’s carrying some baggage herself which contributed to her decision to begin working with those who’ve been convicted of crimes, but is doing it with the aim of reducing suffering and ending the cycle so that there are no more victims or victimisers. Also wounded, Takimoto tells her that murderers aren’t human and can never be rehabilitated, while she’s forced to consider the problem from all angles meeting with a lawyer (Tae Kimura) who defended an abusive husband who murdered his wife and learning that she did so for similar reasons to herself certain that he too deserved a second chance and could perhaps be reformed if given the proper treatment. Kayo sees that many of the people she meets ended up committing crimes because of traumatic personal circumstances and if someone had helped them earlier they may not have offended in the first place. She can’t change the past but at least in helping them now she might prevent further crimes in the future while giving them a source of stability as they attempt to root themselves more firmly in mainstream society.

Inspired by Masahito Kagawa’s manga, Prior Convictions was previously adapted into six-part WOWWOW TV drama to which the film is technically a sequel though fairly stand alone in its gentle unpacking of Kayo’s own unresolved trauma and subsequent epiphanies as regards her relationships with those she’s trying to help. As one young woman puts it, they find her vulnerability reassuring in contrast to the often authoritarian, didactic approaches taken by law enforcement and social services who only talk down to them from a condescending place of superiority rather than trying to meet them on a more human level. In the end it’s about healing, trying to find an accommodation with the traumatic past and limiting its legacy to break the cycle of pain and violence. The prior convictions which most need addressing are those of a judgemental society that all too often contributes to the mechanisms of violence in seeking to punish rather than to help.

Prior Convictions screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

International trailer (English subtitles)