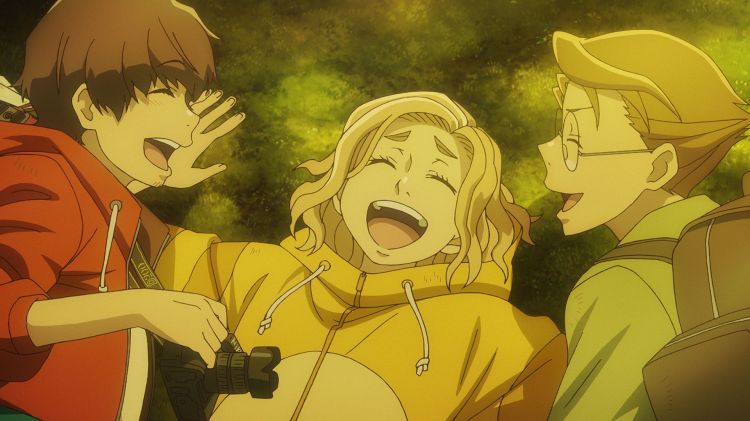

“Don’t forget me” pleads a mysterious young woman guiding the hero of Masakazu Kaneko’s Ring Wandering (リング・ワンダリング) towards the buried legacy he is unwittingly seeking. In this metaphorical drama, the aspiring manga artist hero is on a quest to discover the true appearance of the long extinct Japanese wolf, but is confronted by a more immediate source of unresolved history while working on a construction site for the upcoming Tokyo Olympic Games.

The manga Sosuke (Show Kasamatsu) is working on is about a wolf and a hunter, Ginzo (Hatsunori Hasegawa), whose daughter Kozue was killed by one of his own traps. Though praising the general concept, his workplace friend points out that his manga lacks human feeling but Sosuke claims it’s unnecessary in a story that’s about a duel to the death between man and nature while matter of factly admitting that Kozue is merely a plot device designed to demonstrate Ginzo’s manly solitude. Yet Soskue complains that he can’t make progress because the Japanese wolf is extinct and he can’t figure out how to draw it.

His quest is in one sense for the soul of Japan taking the wolf as a symbol of a prehistoric age of innocence though as it turns out he knows precious little about more recent history. The workers at the construction site have heard rumours about a stoppage at another build and joke amongst themselves that if they should find any kind of cultural artefact they’ll just ignore it rather than risk the project being shut down or any one losing their job. The site itself symbolises a tendency to simply build over the buried past erasing traces of anything unpleasant or inconvenient. When Sosuke comes across an animal’s skull buried in a pit he has recently dug, he is convinced it’s that of a Japanese wolf only later realising it is more likely to be that of a dog killed in the fire bombing of Tokyo during the war along with thousands of others on whose bodies the modern city is said to lie.

Then again, impassive in expression Sosuke is particularly clueless when it comes to recent history. While searching for more wolf cues he comes across a young woman (Junko Abe) looking for her missing dog but completely fails to spot her unusual dress aside from assuming the old-fashioned sandals she is wearing are for the fireworks show set to take place that day incongruously in the winter. Similarly in accompanying her to her home he is confused by all her references to things like the metal contribution and her brother having been sent to the country. He wonders if she might be a ghost, and she wonders the same of him, but still doesn’t seem to grasp that he’s slipped into another era fraught with danger and anxiety only realising the truth on exiting the dream and doing some present day research.

The fallacy of violence works its way into his manga in the fact that Ginzo’s traps eventually lead to the death of his daughter while he becomes on fixated on besting the wild wolf as a point of male pride though others in the village are mindful to let it live. A pedlar meanwhile explains that the wolf has been forced down towards the village because of the declining economic situation as more people hunt in the mountains for food and fur depriving him of his dinner. He tells Ginzo that the country has been “brainwashed in militarism” and the gunpowder that killed Kozue and will one day be repurposed to create joy and awe is now his most wanted commodity. In the end Ginzo too is saved by a kind of visitation, a ghost from the past offering a hand of both salvation and forgiveness along with an admonishment forcing him to take responsibility for his role in his daughter’s death.

In forging a familial relationship with a lost generation Sosuke comes to a new understanding of more recent history and in a sense discovers the connection he was seeking with his culture, weaving the anxieties of 1940s into an otherwise pre-modern fable about the battle between man and nature in which wolf becomes not aggressor but casualty in a great national folly. Like Kaneko’s previous film Albino’s Trees deeply spiritual in its forest imagery and oneiric atmosphere, Ring Wandering finds its hero transported into the past while unwittingly discovering what it is he’s looking for without ever realising that it has always been right beneath his feet.

Ring Wandering streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Images: ©RWProductionCommittee