Sakura, or cherry blossoms, are often seen as emblematic of “Japan”. A potent poetic symbol, they blossom only for a short time and then slowly fade away. In the case of Hiroto Hara’s conspiracy drama SAKURA (朽ちないサクラ, Kuchinai Sakura), however, the title refers to a nickname for the security services. In fact, the title could be read either as the “sakura never decays,” or perhaps “will never be tarnished”, “will never die,” echoing the frequent messages that you can never really escape your past for like sakura it will always blossom again while the security services themselves will never fall.

In this case, the event that reverberates is a nerve gas attack on a station that is clearly an allegory for that conducted by Aum Shinrikyo in 1995. Like Aum which is now known as Aleph, the cult in the movie simply changed its name and carried on. Now the head of the police PR department for which the heroine works, former security agent Togashi (Ken Yasuda), is haunted by a mistake he made as a rookie cop and blames himself for not being able to stop the disaster. As fate would have it, the case they’re currently investigating ties back to the cult suggesting a much wider conspiracy in play than the simple intention to cover up a murder.

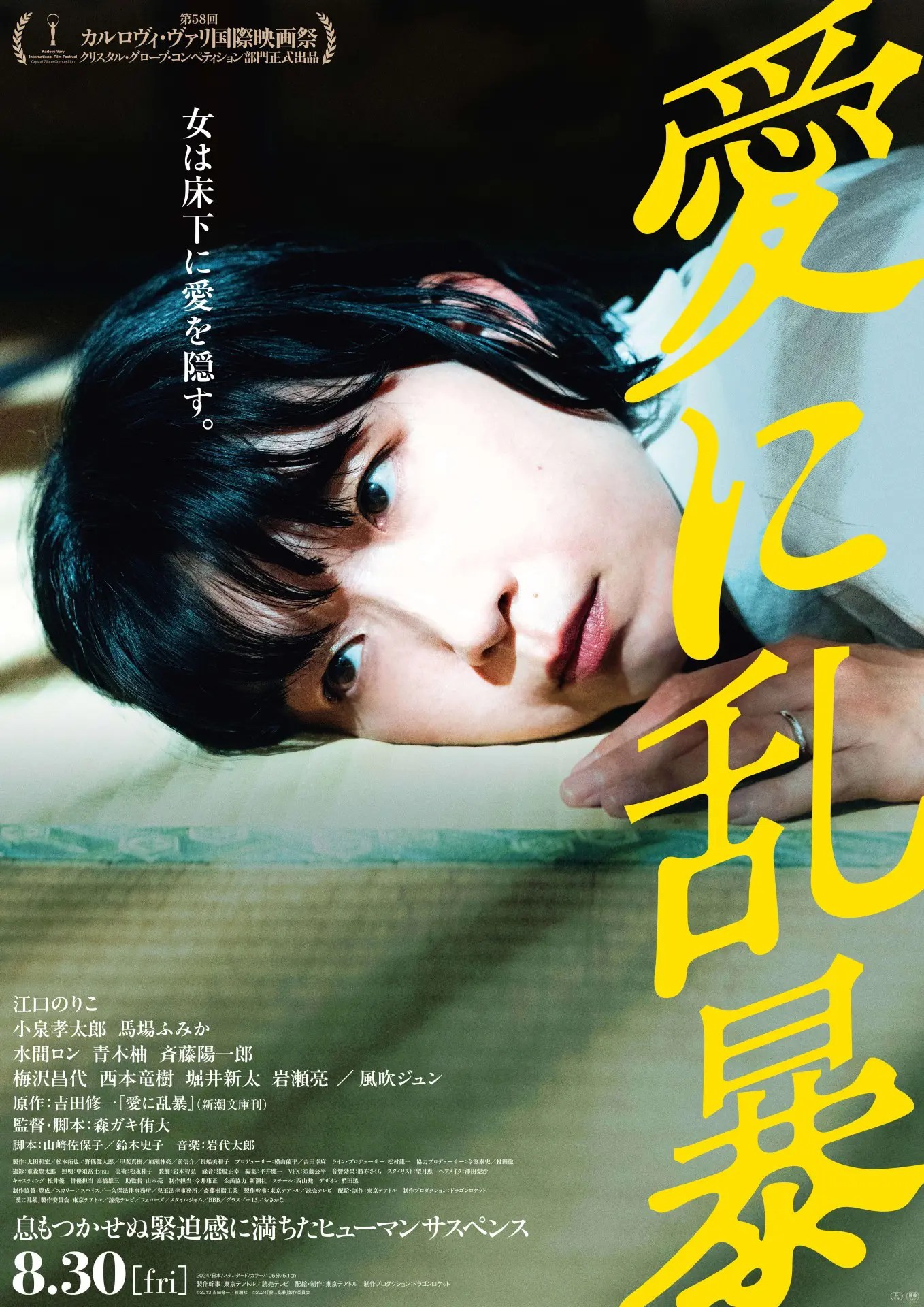

But there are also two killings here that are likely connected, the first being that of a woman whose allegation of stalking was ignored by the police who, rather than investigate, went off to enjoy themselves on some kind of outing The press is having a field day with the implication the police are both lacking in compassion and negligent in their work. Predictably, the PR division’s main intention is to uncover the source of the leak with Togashi seemingly already suspecting a woman in his department, Izumi (Hana Sugisaki), whose boyfriend, Isokawa (Riku Hagiwara), was himself on that outing. Izumi had accidentally let slip about the police’s activities to her best friend Chika (Kokoro Morita), a reporter who works at the local paper that broke the story. Chika insisted it wasn’t her who wrote the article, but Izumi didn’t believe her. Chika is then found dead after vowing to investigate more fully and prove Izumi wrong with an original hypothesis that she took her own life in guilt over betraying her friend.

Obviously, there’s more to it than that and it soon becomes clear she was murdered probably because she got too close to the truth. Izumi isn’t a detective, but finds herself trying to investigate out of a sense that she contributed to Chika’s death by not believing her when she said she never broke the promise she made not to tell anyone else about the police outing. One might legitimately ask why she is allowed to do this, and the lead detective is not originally happy about it, but as they’re grateful for the leads she turns up, Izumi effectively gets a sort of promotion to investigator. Later events might lead us to wonder if she isn’t being manipulated as part of a wider conspiracy, but then the central intention remains unclear as does the reason the shady forces in play would allow her to investigate Chika’s death knowing the possibility that she may stumble on the “real” truth in the process.

It could be that they simply don’t need to stop her because they know there’s nothing she can do. She has no evidence for her final conclusions and no one would believe her if she spoke out, but it seems odd that conspiracists who’ve already bumped off several other people would allow her to simply walk away knowing what she knows if there were not some grander plan in motion. The question is, is it justified to cause the deaths of a small number of people in order to save the lives of hundreds more who might otherwise die if the cult carries out another terrorist attack before they can be stopped? Sakura apparently have spies and informants everywhere and will do everything they can to protect them in order to facilitate their goal of protecting the nation. Thus the famed cherry blossoms now become another symbol of constant threat and oppression in the spectre of the security services who watch and oversee everything but remain in the shadows themselves. Hara homes in on this sense of paranoia and injustice but in the end cannot resist indulging Izumi’s plucky rookie investigator spirit. Her final decision may not make an awful lot of sense while essentially pitting one authority figure against another. Nevertheless, the tension remains high as Izumi presses forward towards the truth no matter what the danger while like her policeman boyfriend determined to pursue justice wherever it may lie.

SAKURA screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Images: ©2024 SAKURA Film Partners