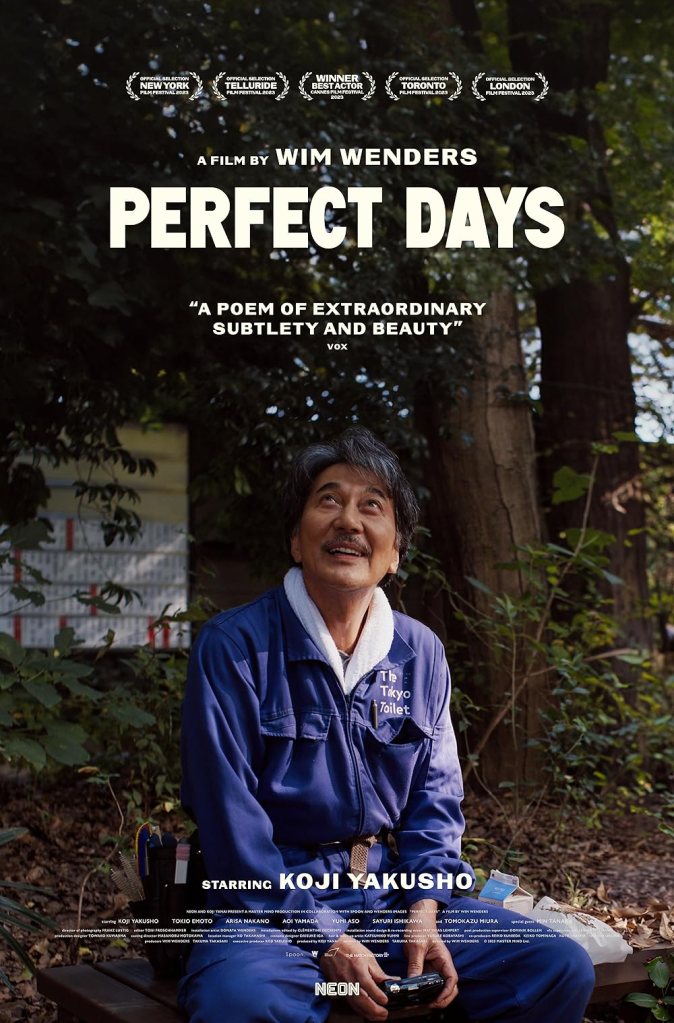

The Japan Academy Film Prize, Japan’s equivalent of the Oscars awarded by the Nippon Academy-Sho Association of industry professionals, has announced the winners for its 47th edition which honours films released Jan. 1 – Dec. 31, 2023 that played in a Tokyo cinema at least three times a day for more than two weeks. Godzilla Minus One takes Best Picture and cleans up in technical categories while actress Sakura Ando scores both supporting and leading awards and Koji Yakusho takes home Best Actor for Perfect Days.

Picture of the Year

- Monster

- Godzilla Minus One

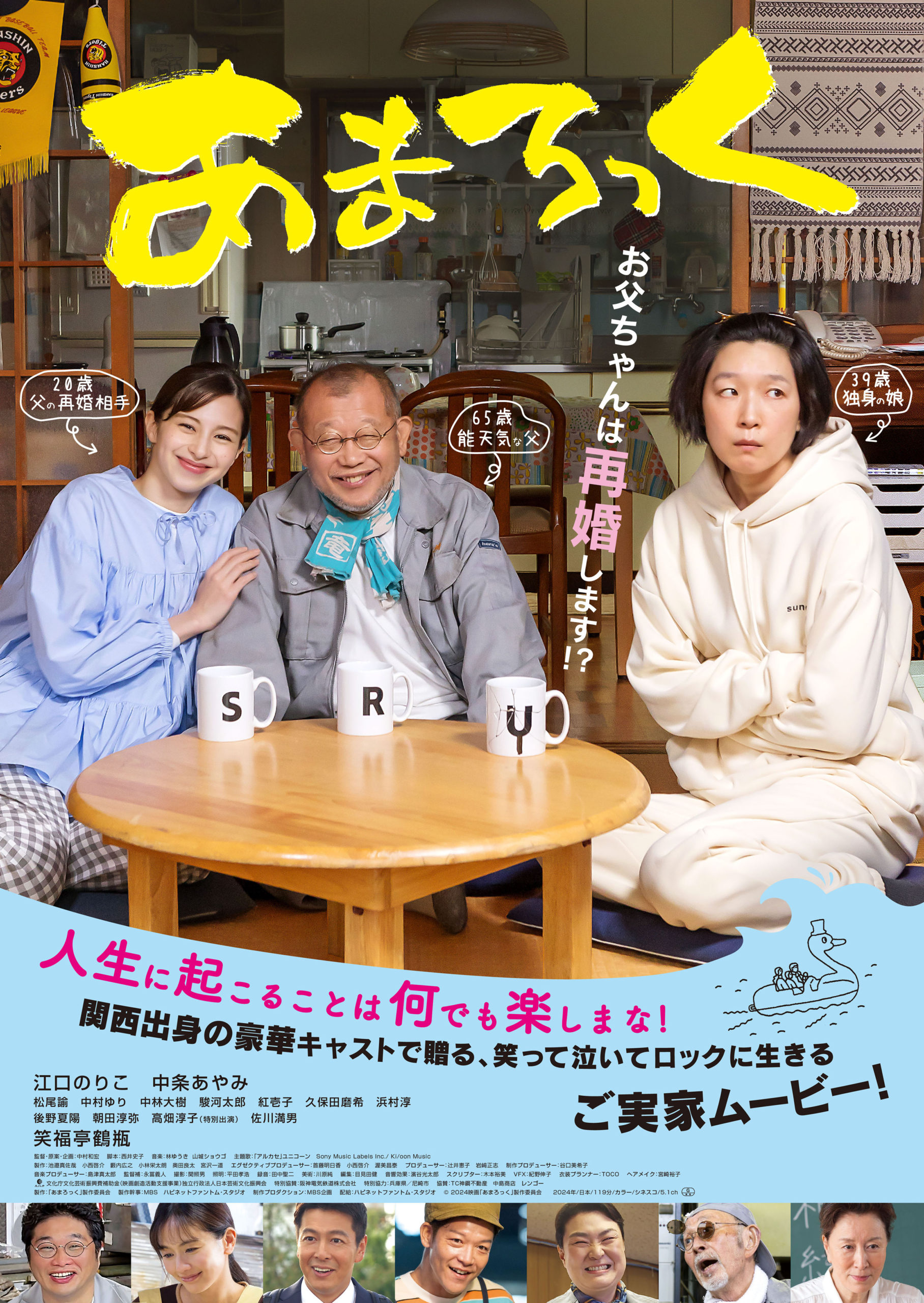

- Mom, Is That You?!

- September 1923

- Perfect Days

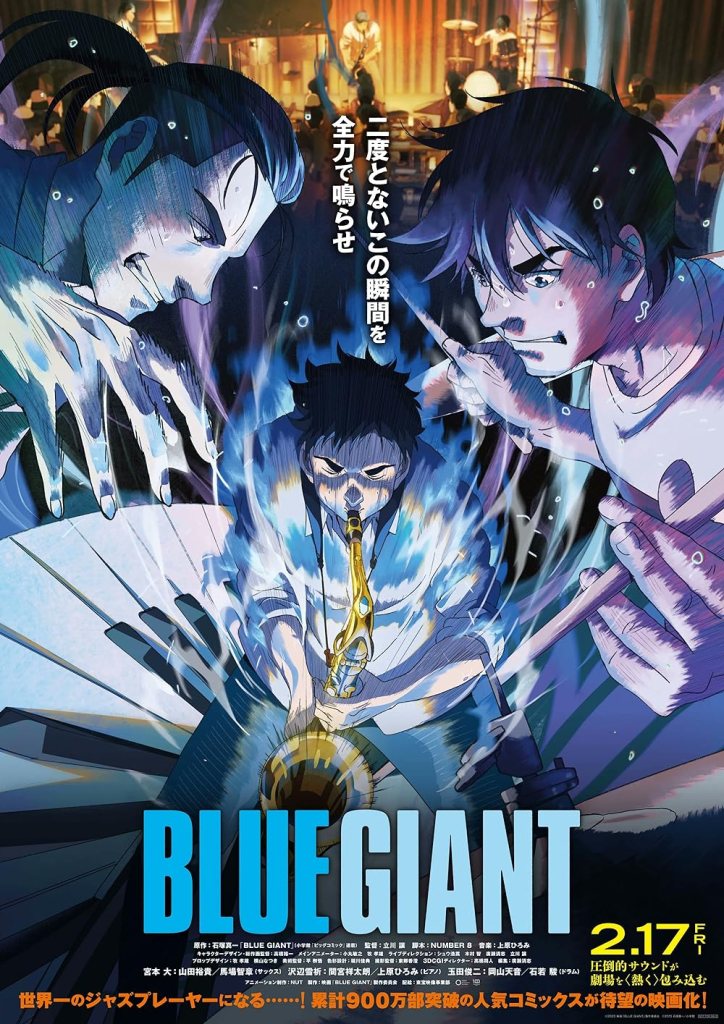

Animation of the Year

- Kitaro Tanjo – GeGeGe no Nazo

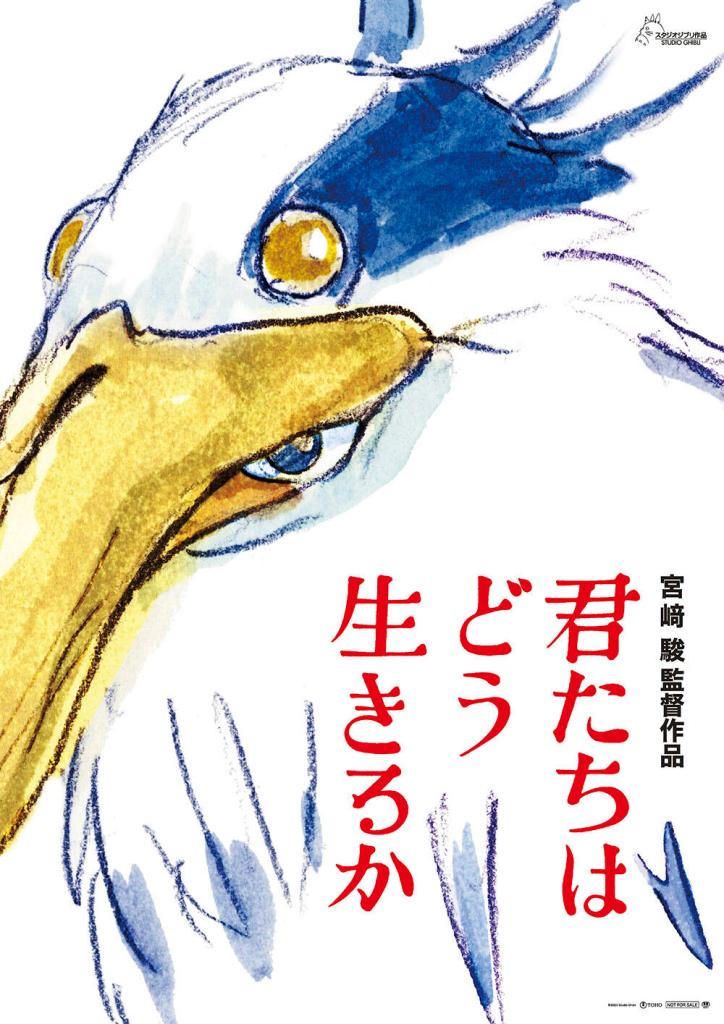

- The Boy and the Heron

- Totto-Chan: The Little Girl at the Window

- Detective Conan: Black Iron Submarine

- Blue Giant

Director of the Year

- Wim Wenders (Perfect Days)

- Hirokazu Koreeda (Monster)

- Yoichi Narita (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Tatsuya Mori (September 1923)

- Takashi Yamazaki (Godzilla Minus One)

Screenplay of the Year

- Toshimichi Saeki, Junichi Inoue, Haruhiko Arai (September 1923)

- Michio Tsubaki (Shylock’s Children)

- Masahiro Yamaura, Yoichi Narita (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Takashi Yamazaki (Godzilla Minus One)

- Yoji Yamada, Yuzo Asahara (Mom, Is That You?!)

Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role

- Sadao Abe (Shylock’s Children)

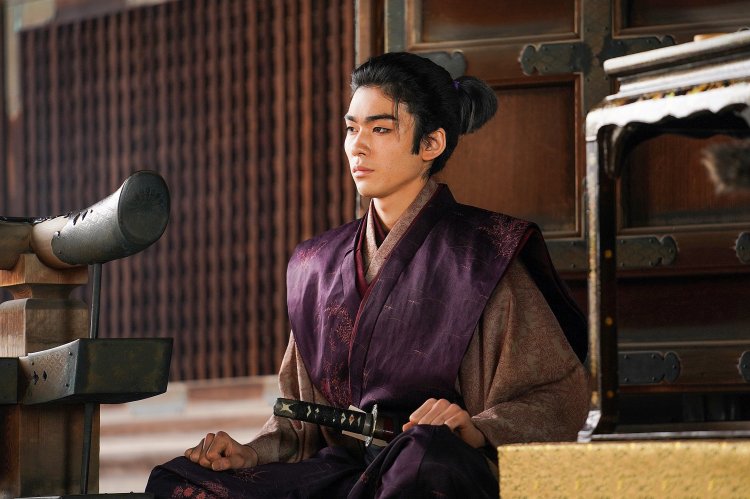

- Kamiki Ryunosuke (Godzilla Minus One)

- Ryohei Suzuki (Egoist)

- Koshi Mizukami (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Koji Yakusho (Perfect Days)

Outstanding Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role

- Haruka Ayase (Revolver Lily)

- Sakura Ando (Monster)

- Hana Sugisaki (Ichiko)

- Minami Hamabe (Godzilla Minus One)

- Sayuri Yoshinaga (Mom, Is That You?!)

Outstanding Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role

- Hayato Isomura (The Moon)

- Kentaro Ito (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Yo Oizumi (Mom, Is That You?!)

- Ryo Kase (Kubi)

- Masaki Suda (Father of the Milky Way Railroad)

Outstanding Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role

- Sakura Ando (Godzilla Minus One)

- Aya Ueto (Shylock’s Children)

- Mei Nagano (Mom, Is That You?!)

- Minami Hamabe (Shin Kamen Rider)

- Keiko Matsuzaka (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography

- Ryuto Kondo (Monster)

- Akira Sako (Kingdom III: Flame of Destiny)

- Kozo Shibasaki (Godzilla Minus One)

- Masashi Chikamori (Mom, Is That You?!)

- Takeshi Hamada (Kubi)

Outstanding Achievement in Lighting Direction

- Eiji Oshita (Monster)

- Hiroyuki Kase (Kingdom III: Flame of Destiny)

- Nariyuki Ueda (Godzilla Minus One)

- Masato Tsuchiyama (Mom, Is That You?!)

- Hitoshi Takaya (Kubi)

Outstanding Achievement in Music

- Hiromi (Blue Giant)

- Takeshi Kobayashi (Kyrie)

- Ryuichi Sakamoto (Monster)

- Naoki Sato (Godzilla Minus One)

- Akira Senju (Mom, Is That You?!)

Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction

- Anri Johjo (Godzilla Minus One)

- Yukiharu Seshimo (Kubi)

- Takashi Nishimura (Mom, Is That You?!)

- So Hashimoto (Legend & Butterfly)

- Keiko Mitsumatsu, Seo Hyeon-seon (Monster)

Outstanding Achievement in Sound Recording

- Kentaro Suzuki (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Yasuo Takano (Kubi)

- Hisafumi Takeuchi (Godzilla Minus One)

- Kazuhiko Tomita (Monster)

- Shota Nagamura (Mom, Is That You?!)

Outstanding Achievement in Film Editing

- Norihiro Iwama (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Takeshi Kitano, Yoshinori Ota (Kubi)

- Hirokazu Koreeda (Monster)

- Hiroshi Sugimoto (Mom, Is That You?!)

- Ryuji Miyajima (Godzilla Minus One)

Outstanding Foreign Language Film

- Killers of the Flower Moon

- Barbie

- Driving Madeleine

- Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One

- Tar

Newcomer of the Year

- Aina The End (Kyrie)

- Hiyori Sakurada (Our Secret Diary)

- Nanoka Hara (Don’t Call it Mystery)

- Haruka Fukuhara (Till We Meet Again on the Lily Hill)

- Ichikawa Somegoro VIII (The Legend & Butterly)

- Soya Kurokawa (Monster)

- Fumiya Takahashi (Our Secret Diary)

- Hinata Hiiragi (Monster)

Special Award from the Association

- Koji Omura (hair and makeup)

- Yumiko Kuga (casting)

- Teruyuki Hyakusoku (Steenbeck editing table sales, maintenance, inspection, and repair)

- Keizo Murase (special effects model sculptor)

Award for Distinguished Service from the Chairman

- Norimichi Ikawa (art director)

- Masaharu Ueda (cinematographer)

- Akira Kobayashi (actor)

- Tadashi Sakai (art director)

- Yoichi Higashi (director)

- Kazuo Yabe (lighting)

Special Award from the Chairman

- Ryuichi Sakamoto (composer)

- Shuji Abe (producer)

Special Award

- Cine Bazar

- Tokyo Laboratory

Popularity Awards

(Decided via public vote)

Movie: kyrie

Actor: Yuki Yamada (Kingdom III: Flame of Destiny, Godzilla Minus One, Tokyo Revengers 2 : Bloody Halloween : Destiny / Decisive Battle, Blue Giant)