War, in Japanese cinema, had been largely relegated to the samurai era until militarism took hold and the nation embarked on wide scale warfare mixed with European-style empire building in the mid-1930s. Tomotaka Tasaka’s Five Scouts (五人の斥候兵, Gonin no Sekkohei) is often thought to be the first true Japanese war film, shot on location in Manchuria and trying to put a patriotic spin on its not entirely inspiring central narrative. Like many directors of the era, Tasaka is effectively directing a propaganda film but he neatly sidesteps bold declarations of the glory of war for a less controversial praise of the nobility of the Japanese soldier who longs to die bravely for the Emperor and lives only to defend his friends.

War, in Japanese cinema, had been largely relegated to the samurai era until militarism took hold and the nation embarked on wide scale warfare mixed with European-style empire building in the mid-1930s. Tomotaka Tasaka’s Five Scouts (五人の斥候兵, Gonin no Sekkohei) is often thought to be the first true Japanese war film, shot on location in Manchuria and trying to put a patriotic spin on its not entirely inspiring central narrative. Like many directors of the era, Tasaka is effectively directing a propaganda film but he neatly sidesteps bold declarations of the glory of war for a less controversial praise of the nobility of the Japanese soldier who longs to die bravely for the Emperor and lives only to defend his friends.

The film opens with an exciting action sequence playing behind the titles featuring impressive scenes of battle with mortar shells exploding while soldiers run over trenches before entrenching themselves with a light machine gun. Eventually the day is won – after a fashion. Having lost 120 men, the 80 surviving of the 200 strong company settle-in to a fortified position awaiting further orders.

The excitement of the battlefield soon gives way to behind the lines boredom. Danger lurks around every corner, but there is work to be done. The men dig trenches, clean their weapons, draw water, cook and eat but they also try to live, chatting or enjoying the “spoils of war” which in this case amount to stolen watermelons and captured ducks. In quiet moments they dream of sukiyaki and of home, but are content in each other’s company and as cheerful as it’s possible to be given the seriousness of their circumstances.

When two enemy soldiers are detected on the perimeter, a squad of five scouts is sent out to investigate but find themselves lost in the confusing Chinese terrain and eventually come under heavy fire. Worryingly enough, only one of the soldiers makes it back in good time with the others remaining unaccounted for until they eventually arrive save one who no one can remember seeing since the beginning of the attack and whose helmet has been found in an abandoned trench.

Tasaka refuses to glorify the business of war. What the men experience is rain and mud and sorrow, not an exultation in male virility and the politics of strength. He does however fulfil his propaganda requirements in demonstrating the army’s dedication to the Emperor. The commanding officer’s final rousing speech reminds his troops that now is the time they are expected to “repay the benevolence of the Emperor” whilst also emphasising that the hopes and dreams of the Japanese people are invested in them and, even if their families at home are worried for their safety, they are also proud of their sons fighting proudly for their homeland so far away from home.

The men too display the appropriate level of patriotic fervour, breaking off to wave at a Japanese plane before dragging out a giant banner to show their support and each remaining committed to serving even when physically compromised. One soldier with a bullet lodged in his arm, violently rejects the idea of going to a field hospital even though there is a strong chance that his arm will need to be amputated if they do not remove the bullet in due time. The soldier pleads to be allowed to stay on the front line, claiming that he does not mind losing an arm if it means he gets to stay and help his comrades. His comrades, touched by his dedication, nevertheless urge him to get his arm seen to by subtly suggesting that his desire to remain on the frontline is a kind of vanity when his effectiveness is compromised. His arm, technically speaking, does belong to the army and the Emperor after all. Another soldier, not so lucky, exclaims he can see Japan as he lays dying, singing the first verse of the national anthem before finally giving up the ghost.

As the men march off towards the final battle following the rousing speech from their commander who warns that many will die, they do so melancholically rather than with eagerness to sacrifice themselves on an imperial altar. Tasaka stages the battle scenes with impressive realism, drawing inspiration from news reel footage to capture the immediacy and energy of the live battlefield, filming on location behind the lines in Manchuria for added effect. The behind the lines sequences are intentionally less dynamic and conventionally captured, allowing the tedium and the anxiety of a soldier’s life of waiting to take centre-stage. Tasaka’s film may seem naive and perhaps lacks the initial impact of the shock of seeing such visceral action scenes portrayed on screen for the first time, but it is also mildly subversive in its subtle rejection of the militarist lust for glory even whilst heaping praise on the ideal soldier’s love of Emperor, comradeship, and strong sense of duty and honour.

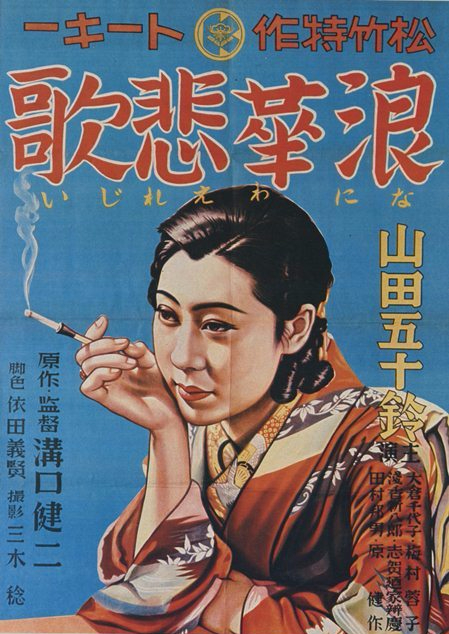

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old.

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old. Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to

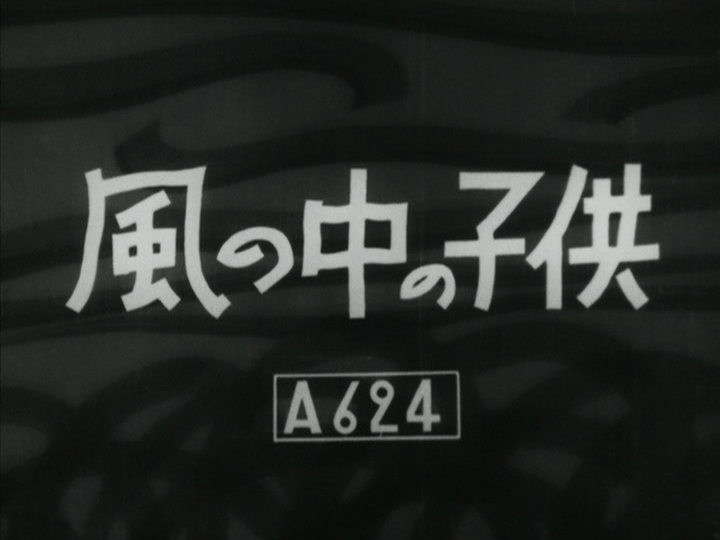

Isn’t it sad that it’s always the kids that end up hurt when parents fight? Throughout Shimizu’s long career of child centric cinema, the one recurring motif is in the sheer pain of a child who suddenly finds the other kids won’t play with him anymore even though he doesn’t think he’s done anything wrong. Four Seasons of Children (子どもの四季, Kodomo no Shiki) is actually a kind of companion piece to  It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.