Examining the few films which have survived from the colonial era, signs of resistance are few and far between even if there is often a degree of subversion detectable in foregrounding of background issues such as continuing poverty or patriarchal oppression. 1941’s Spring of the Korean Peninsula (반도의 봄, Bandoui Bom), however, appears much more complex than it might at first seem. Ostensibly a tale of the trials and tribulations of would-be-filmmakers in underpowered Korea, Lee Byung-il’s debut feature undercuts its eventual slide into one nation propaganda through the background presence of its sullen director who is forced to bear all stoically while seemingly dying inside.

Examining the few films which have survived from the colonial era, signs of resistance are few and far between even if there is often a degree of subversion detectable in foregrounding of background issues such as continuing poverty or patriarchal oppression. 1941’s Spring of the Korean Peninsula (반도의 봄, Bandoui Bom), however, appears much more complex than it might at first seem. Ostensibly a tale of the trials and tribulations of would-be-filmmakers in underpowered Korea, Lee Byung-il’s debut feature undercuts its eventual slide into one nation propaganda through the background presence of its sullen director who is forced to bear all stoically while seemingly dying inside.

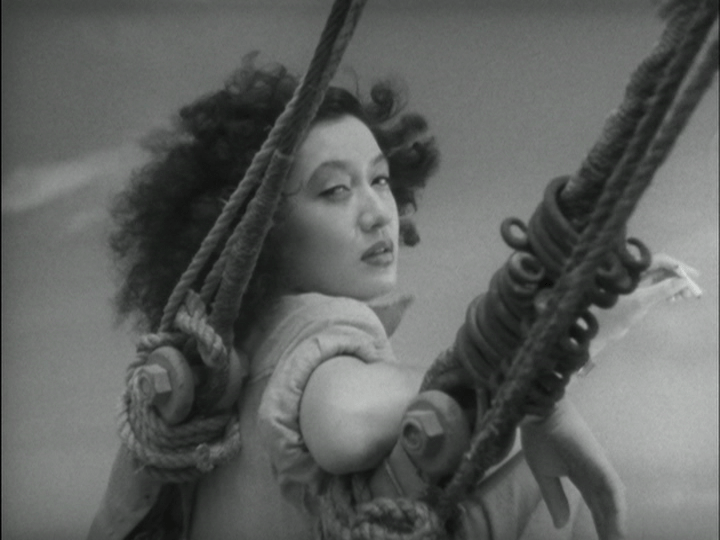

The action begins in the contemporary era (and not) as we see the heroine of the film director Heo Hoon (Seo Wol-young) is trying to make strum a gayageum before her lover arrives and the camera pulls back to reveal that we are on a film set. Attempting to film another version of the famous folktale in which the scholar Mong-ryong falls in love and secretly marries the lowborn daughter of a gisaeng, Chun-hyang, only for their romance to be threatened by a corrupt and lecherous lord, Heo has several problems to contend with, the most serious being a severe lack of money and the second being the unhappiness of his leading actress, An-na (Baek Ran), who eventually quits the production without warning.

Meanwhile, film producer Yeong-il (Kim Il-hae) welcomes an old friend en route to study in Tokyo who has brought along his little sister, Jeong-hee (Kim So-young), who is desperate to get into films. Rather than immediately ask her over to his film set, Yeong-il fobs Jeong-hee off by advising she continue her music career, offering to introduce her to a record producer he knows, Han (Kim Han), who is actually bankrolling his film as a vehicle for An-na who is his current main squeeze. Unfortunately for everyone, Han is a serial womaniser who takes a liking to Jeong-hee which causes a rift in his relationship with An-na who quits movies to go back to bar work. Jeong-hee gets the part (without really understanding why) but when Han declares himself out of money (at least, out of money when it comes to Heo’s personal expenses), Yeong-il makes a fateful decision in misappropriating some funds in the belief that he can make up the money when a cheque he’s expecting from a competition eventually comes through.

Despite the setting there is relatively little overt mention of the Japanese until the film’s conclusion when a new film company has finally been formed leading to a speech from the chairman to the effect that they now have a new duty to sell the one nation idea to the masses as loyal subjects of the Japanese empire. Lee Byung-il, like the majority of directors in this era, had himself trained in Japan and perhaps shared Heo’s envy in the established nature of the Japanese film industry which was well funded, economically successful, and technologically advanced. The more positive of Heo’s colleagues hope that the new collaborations with Japan will lead to an upgrade in the positioning of the Korean film industry but Heo is not so sure. Seated at the dinner and listening the propagandistic speeches he sits impassively while staring sadly into the middle distance as he watches Yeong-il prepare for his mission to Japan in which he is supposed to tour the film studios and bring what he’s learned back to Korea.

Meanwhile, Heo can’t pay his rent and is living on scraps and passion. His story is, however, somewhat peripheral as we become embroiled in the central melodrama of the love quadrangle developing around Jeong-hee, Yeong-il, An-na, and Han. An-na, who is looked down on as people suspect her of having worked in the sex industry in Tokyo which is probably where she met Han, is aware that he will soon tire of her and has fallen for “nice guy” Yeong-il who remains completely oblivious to the fact that both she, and the little sister of his best friend Jeong-hee, have fallen in love with him. Han, meanwhile, is a serial sexual harasser as his assistant tries to signal Jeong-hee even while being unable to prevent her getting into his car on her own.

Interestingly enough, “bad girl” An-na only speaks Japanese, while “nice girl” Jeong-hee only speaks Korean and dresses mostly in hanbok though many of her scenes feature her playing the heroine of Chun-hyang who, it could be argued, is a kind of embodiment of “Korea”. The choice of Chun-hyang is in itself subversive in its obvious “Koreanness” let alone the persistent subtext that positions the retelling as that of a purehearted Korea struggling against the “corruption” of the Japanese colonial regime as embodied by the piece’s villain. Nevertheless, the love square resolves itself in unexpected fashion as the two women bond over their shared love of Yeong-il. An-na, forced to reflect on her “problematic” past, eventually makes a pure love sacrifice to clear the way for the two “nice” kids to get together, becoming a figure of intense sympathy as she absents herself from the frame to exorcise the kind of “corruption” she has been used to represent from the innocent romance of Jeong-hee and her real life Mong-ryong Yeong-il.

Lee would make no further films during the colonial era. In 1948 he left Korea to train in Hollywood and then sat out the Korean War in Japan, only returning to Korea in 1954. After setting up his own studio, Donga Film Company, Lee went on to direct Korea’s “first” comedy The Wedding Day and thereafter to a hugely successful career. Like Heo, it seems he remained pessimistic and conflicted about the Korean film industry’s increasing dependence on Japan (despite his personal experiences). Nevertheless, his debut strikes a surprising note of discordance in its subversive themes and melancholy closing as its director stares ambivalently into an uncertain future, left behind as his emissaries ride off in search of a new and more modern world.

Spring of the Korean Peninsula was screened as part of the Early Korean Cinema: Lost Films from the Japanese Colonial Period season currently running at BFI Southbank. Also available to stream online via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.

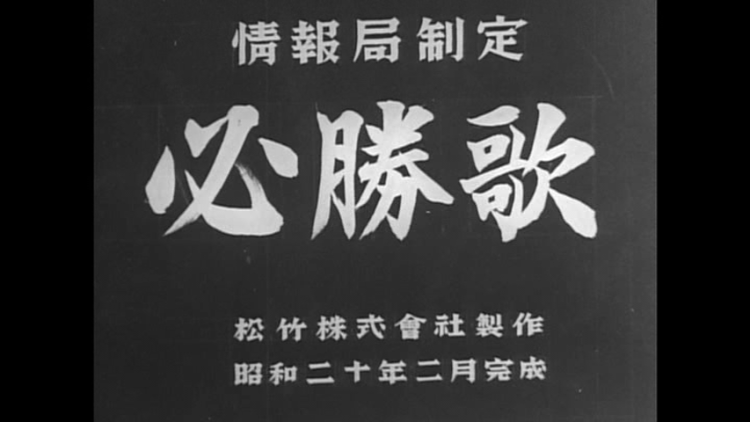

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles.

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles. Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way.

Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way.