“I wish I were younger” comes a common refrain among the cast of elderly men and women living a traditional life in the mountains and forests of rural Japan in Naomi Kawase’s 1997 documentary, The Weald. Arriving in the same year as Kawase’s Caméra d’Or-winning narrative feature Suzaku, The Weald (杣人物語, Somaudo Monogatari) continues many of the same themes in her fascination with nature and moribund ways of life while taking on a meta existential dimension as her interviewees muse on loss, loneliness, and a lifetime’s regrets.

What they almost all say is that they wish they could be young again with all the possibilities of youth. A lumberjack dreams of becoming a timber dealer, while another man jokes that he was once handsome though you wouldn’t know it now. One heartbreakingly laments that he’d like to start over because he’s never felt true happiness in his life. Then again, another believes that “happiness depends on your way of thinking” and that a man who’s learned to be satisfied with a small portion is in his own way rich. For another man happiness lies in having people speak well of him after he’s gone, knowing he must then have lived a good life.

Then again life has its sadnesses. A carpenter reveals his private grief in having lost a son, unable even to watch his daughter’s wedding video because it’s too painful to see him there. “In a city he wouldn’t have had a motorbike” he sighs, reflecting that he was unlucky to have been born in the country and needlessly blaming himself for something not in his control. The last man, meanwhile, speaks movingly of his late mother’s descent into dementia and his own decision to give up on marriage while still young to dedicate himself to her, only to be left on his own in the end. He wonders if he was right to sacrifice his life for her while longing to be reborn in the hope of seeing his former girlfriend, his face dissolving into an old photograph in which he is young and handsome as if to grant his wish.

Meanwhile, an old lady meditates on loneliness in a solo life of busyness firstly claiming to feel none but then revealing the emptiness of her days with no one to cook for. “I don’t know the meaning of life, I just live day to day” she explains, insisting that it’s pointless to worry and better just to get on with things. “I am satisfied to live each day peacefully” she adds, immersing herself in the moment. She like the others is uncertain why Kawase is filming her, telling her to come back later when she’s 18 again because old people are no fun. Another man later tells her not to waste her expensive film on him in case she needs it for something more important, the elderly residents either maudlin or amused but each mystified as to why someone is so keen to listen to their stories.

Implicitly in these stories of the elderly, Kawase hints at the effects of continuing rural depopulation with fewer young people around, an elderly couple explaining that they have come to depend on each other even more as they aged only for the wife to fall ill and need care from her husband 14 years older but in better health. They go about their lives in the same way they have for decades, wandering the forests and practicing traditional skills which may all too soon be lost.

In keeping with her earlier documentary work, Kawase often films in extreme close up or layers dialogue on top of another scene as when old lady wanders aimlessly trough the forest while her meditations on loneliness accompany her. What she seems to have discovered in the wisdom of those who agreed to speak to her is that happiness and suffering go hand in hand while youthful regret tinged with nostalgia can in itself almost be lonely. Even so many have managed to find meaning in their lives whether it be being present in nature or the love for one’s spouse and family while longing to be reborn eager for their next lives whatever they will be. “I wish only the best for everyone” someone adds before returning at last to spring and all the brief joys it will deliver.

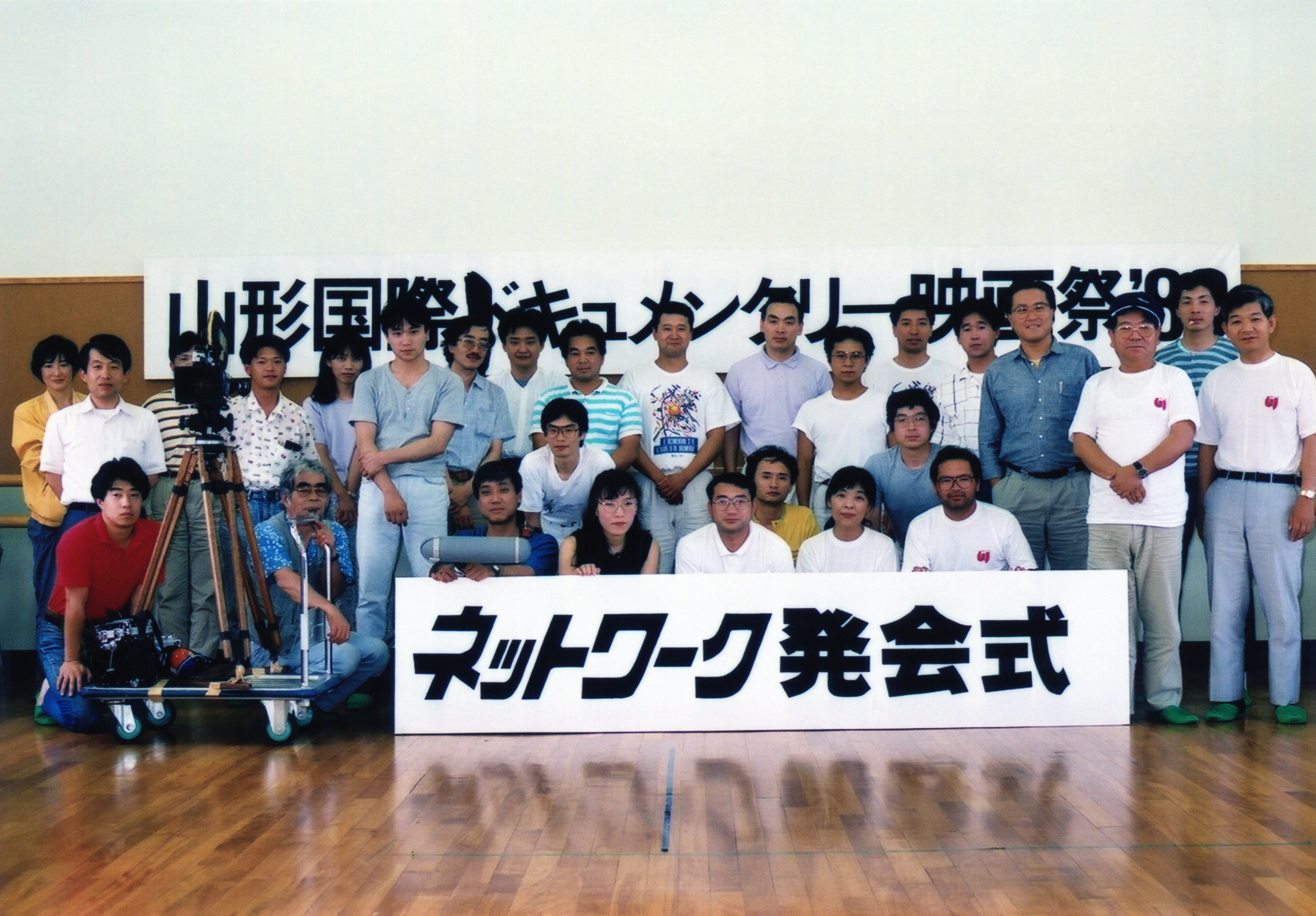

The Weald streams worldwide (excl. Japan) via DAFilms until Feb. 6 as part of Made in Japan, Yamagata 1989 – 2021 (films stream free until Jan. 24)

Trailer (no subtitles)