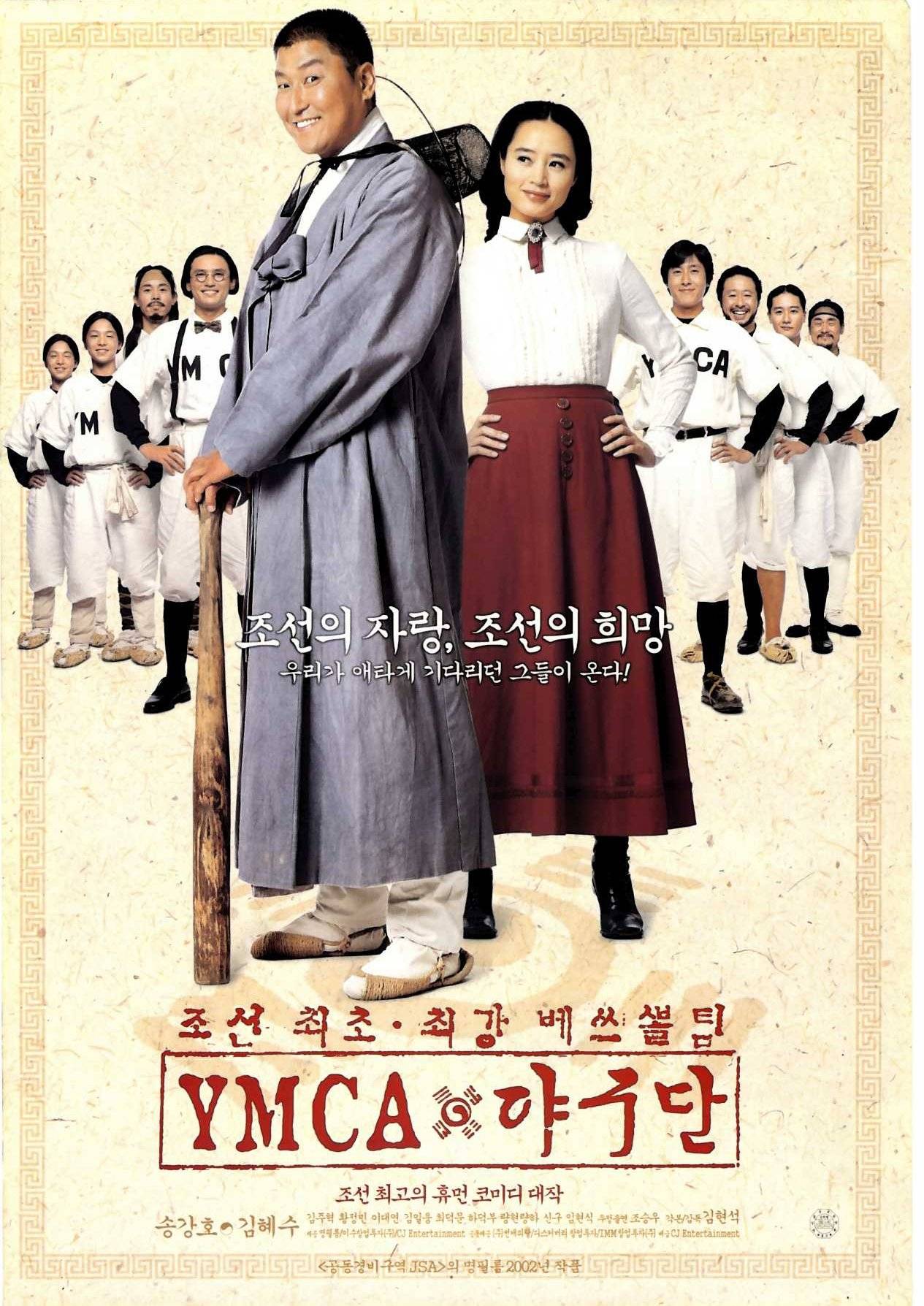

Kim Hyun-seok’s sporting comedy YMCA Baseball Team (YMCA 야구단, YMCA Yagudan) opens with sepia-tinted scenes of Korea in 1905 in which most people still wear hanbok and live little differently than their distant ancestors. Modernity is, however, coming as evidenced by the streetcar that runs through the centre of town even if it’s surrounded on both sides by unpaved ground. Reluctant scholar Hochang’s (Song Kang-ho) father (Shin Goo) complains that the cranes no longer stop in Seoul. Too many scholars have picked the wrong side, he says, but Hochcang counters him that these days you can get to Incheon in hour by train. Maybe the cranes are saying there’s no need to emulate them anymore.

Hochang doesn’t want to be a scholar or take over his father’s school. His father wanted his brother to do that anyway, but he’s run off and joined the resistance to the Japanese. Just as Hochang discovers the new sport of baseball thanks to a pair of American missionaries and the pretty daughter of a diplomat, the Japanese further increase their dominance over Korea by forcing it to sign the Eulsa Treaty in which they effetively ceded their sovereignty and gave additional provisions for Japanese troops to remain in their nation.

Hochang had been playing football alone as his friend practised reading English before he kicked a ball into Jungrim’s (Kim Hye-soo) garden and found a baseball instead. The early scenes see the local population adopting this Western game in makeshift fashion, using paddles and tools as bats while putting festival masks on their faces in weaponising their culture to make this sport their own. In baseball, Hochung finds the vocation he hasn’t found in scholarship or anywhere else. As a child, he wanted to be a King’s Emissary, but the Korean Empire is drawing to a close and the position no longer exists. His battle is in part to be able to live the life he chooses rather than simply continue these ancestral traditions and be a teacher like his father. In a cute public event unveiling the team, children sing a song in which little boys sing about how they don’t want to be an admiral as their fathers wanted them to be but want be something else, while the girls don’t want to marry a powerful man as their mother’s advised, but would rather marry someone else. The joke is that they both want to be or be with the YMCA Baseball Team, which has, in its way come, to represent a new modernising Korea that is keeping itself alive by embracing the new.

To that extent, Jongrim herself comes to represent “Korea” in that Hochang uses his scholarly skills to write her a love scroll in beautiful calligraphy, but it somehow gets mistaken for her father’s will and read out at his funeral after he takes his own life to protest the Eulsa Treaty. Hochang’s heart felt and rather florid poem is then reinterpreted to reflect her father’s “love” for Korea which has been stolen from him by the Japanese. Jungrim and her Japanese-educated friend Daehyun (Kim Joo-hyuk) are secretly in the Resistance and later forced into hiding when Hochung’s friend Kwangtae (Hwang Jung-min) figures out that it was Daehyun who attacked his politician father for betraying the nation by letting the Eulsa treaty pass.

The baseball team becomes another resistance activity, with Jongrim admitting that the people “became one and felt proud” every time the team won. When they discover that their training ground has been commandeered by Japanese troops, they end up agreeing to play them to reclaim their lost territory. But the Japanese still have superiority over an underdeveloped Korea as seen in the opening footage as they started playing baseball 30 years earlier. Just as Hochang didn’t want to be a scholar, general’s son Hideo (Kazuma Suzuki) didn’t want to be a soldier either, but in a world of rising militarism he had little choice. His father thinks baseball’s a silly waste of time too, and like Hochang’s father is secretly proud of his son when he’s doing well, but is very clear that this game cannot be lost because the great Japanese Empire cannot be seen to lose to the nation it is currently in the process of subjugating. The day is saved, ironically, by Hochang’s royal seal, given to him by Jongrim, who seems to have returned his affections even if she had a greater cause. The baseball team even allows a snooty former nobleman to accept that class divisions no longer exist and he can in fact be friends with a peasant, especially when they’re uniting in a common goal like kicking out the Japanese. Sadly, the Japanese turned out to be not such good sportsmen after all, and predictably sore losers, but Hochang has at least found a way to resist and fight for a Korea that is free of both onerous tradition and colonial oppression.

YMCA Baseball Team screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety.

Yoshimitsu Morita had a long standing commitment to creating “populist” mainstream cinema but, perversely, he liked to spice it with a layer of arthouse inspired style. 2002’s Copycat Killer(模倣犯, Mohouhan) finds him back in the realm of literary adaptations with a crime thriller inspired by Miyuki Miyabe’s book in which the media becomes an accessory in the crazed culprit’s elaborate bid for eternal fame through fear driven notoriety.