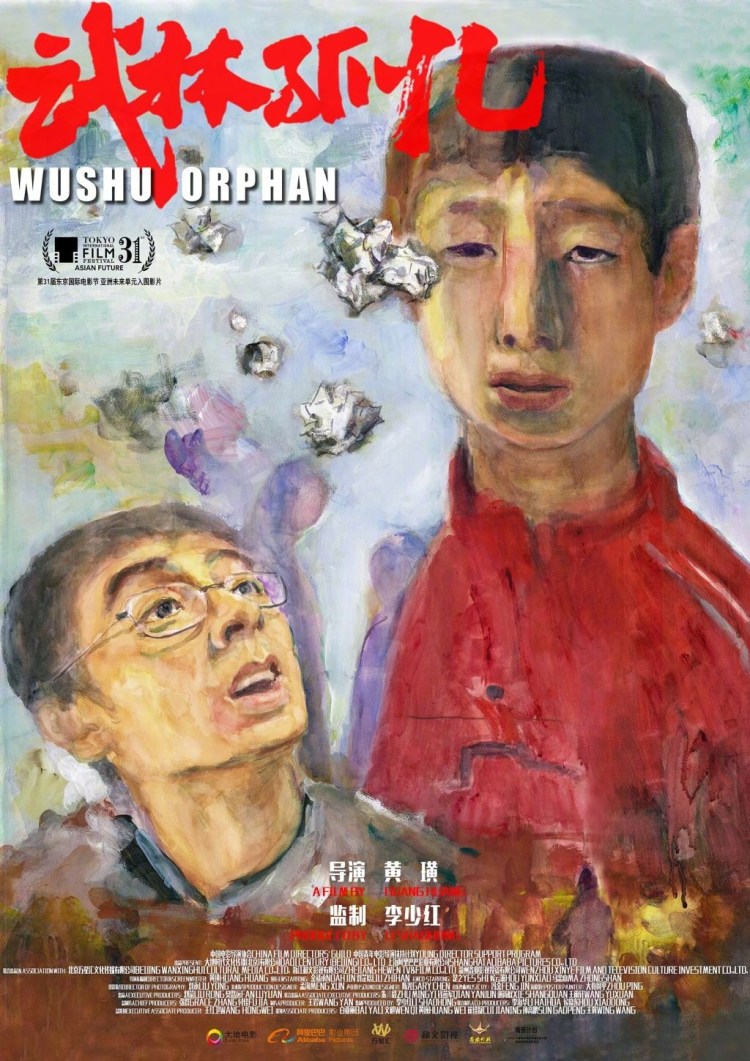

Anti-intellectualism comes in for a subtle kicking in Huang Huang’s whimsical ‘90s drama Wushu Orphan (武林孤儿, Wǔlín Gū‘ér). Less a tale of martial arts, Huang’s poetic debut suggests that perhaps brawn is always going to win over brain, but as brain has the moral high ground it needs to keep fighting all the same even if all it can do is mentally resist. Set in the modernising China of the late ‘90s, Wushu Orphan conjures an achingly nostalgic picture of sleepy rural life, burdened as it is by visions of the past as the next generation pin their hopes on becoming the new Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and Jet Li all while neglecting their studies in expectation of martial arts glory.

Anti-intellectualism comes in for a subtle kicking in Huang Huang’s whimsical ‘90s drama Wushu Orphan (武林孤儿, Wǔlín Gū‘ér). Less a tale of martial arts, Huang’s poetic debut suggests that perhaps brawn is always going to win over brain, but as brain has the moral high ground it needs to keep fighting all the same even if all it can do is mentally resist. Set in the modernising China of the late ‘90s, Wushu Orphan conjures an achingly nostalgic picture of sleepy rural life, burdened as it is by visions of the past as the next generation pin their hopes on becoming the new Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and Jet Li all while neglecting their studies in expectation of martial arts glory.

Our hero, Lu Youhong (Jin Jingcheng), has just transferred to Zhige Wushu Academy to take up a post as their new Chinese teacher. In actuality, Youhong doesn’t have much of an education himself. He has no degree and is almost entirely self-taught which is why he’s wound up here after being turned down by everyone else. In fact, he only got this job because his uncle (Ma Zhongshan), who works at the school, has brought him in as a “catfish” to stir up the otherwise stagnant educational environment which is mainly inhabited by meat headed martial arts fanatics.

Unfortunately for Youhong, no one is very interested in education. All the kids just want to be the next Bruce Lee, and you don’t need to memorise the story of Mulan to become a martial arts master. Zheng Cuishan (Hou Yunxiao), however, has already memorised Mulan, and all the other poems in their reader too. He read them in their entirety when they were first assigned. The problem is, that Zheng Cuishan has been labelled a “special case”. With no aptitude for wushu, he’s mercilessly bullied by his classmates and is forever trying to run away. All he wants is to go home to his family, but they’re fishermen and Zheng Cuishan is afraid of the water so they can’t take him with them on their boat.

As might be assumed, the nerdy, bespectacled Youhong quickly notices an affinity with the obviously bright Cuishan who effortlessly aces all his tests and outright refuses to engage in violence. During one of his earliest lectures, Yuhoung breaks down the character in the name of their school which means “wushu”, explaining that it’s made up of the characters for “stop” and “weapons” because the point of martial arts is to preserve “peace”. His rationale provokes only bored stares from boys who’d rather be outside and a cynical laugh from feckless headmaster’s son Qin (Shi Zhi), lurking outside the window, while he struggles to impress upon his pupils the importance of knowledge as a compliment to physicality.

Going through their tests one day, after being unexpectedly asked to teach maths (and English) after the other teachers quit, Youhong notices that one of the boys got all the questions right but erased his answers before turning in the paper. Confused, he turns to his uncle for an explanation only to be told not to press the issue. This is a martial arts school. It’s considered deeply uncool to be seen succeeding in anything that’s not wushu, as if that were somehow a betrayal or a sign that one has not dedicated oneself entirely to martial arts. That’s one reason Cuishan is so mercilessly bullied, because he’s the intellectual holdout in a school full of meat headed cowards too afraid to buck the system or too brainwashed to know why they should.

In a moment of madness, Youhong snaps, cruelly crushing the dreams of his young charges when he tells them that martial arts are useless in the modern world. They’ll never be the next Bruce Lee, all they can hope for is a life of petty crime and street performance. Predictably he’s silenced by a fist headed straight for his face as if to say that violence is always going to win over rational thought, but Youhong refuses to be beaten. Even if he cannot “fight” these ideas he can still resist them by sticking to his principles and refusing to go along with the inherent weirdness of the school.

In this Cuishan follows him, no longer quite so afraid of the water and one step closer to achieving his dream of learning to swim. Perhaps if Youhoung has encouraged one mind away from the groupthink he’s done enough, emerging with a new conviction as he bravely stands up to a rude woman and her son “threatening” him with a toy gun on the train. Meanwhile, a 70-year-old martial arts master gets of out prison and pointlessly tracks down his geriatric rivals in order to prove himself the master of masters. Filled with nostalgic ‘90s Mandopop and an evocative retro score, Huang Huang’s debut is a visually striking tribute to the solidarity of outsiders swimming against the tide as they strive to keep hold of themselves in the oppressive groupthink of a relentlessly conformist society.

Wushu Orphan screens as part of the 2019 New York Asian Film Festival on June 30.

Original trailer (English subtitles)