“How could the gods be so cruel” a cải lương performer intones, “Allowing us to be together yet worlds apart”. An achingly nostalgic return to the Saigon of the 1980s, Leon Le’s melancholy debut Song Lang is a lament for frustrated connections and the inevitability of heartbreak, taking its lonely heroes on a slow path towards self realisation only to have fate intervene at the worst possible moment.

“How could the gods be so cruel” a cải lương performer intones, “Allowing us to be together yet worlds apart”. An achingly nostalgic return to the Saigon of the 1980s, Leon Le’s melancholy debut Song Lang is a lament for frustrated connections and the inevitability of heartbreak, taking its lonely heroes on a slow path towards self realisation only to have fate intervene at the worst possible moment.

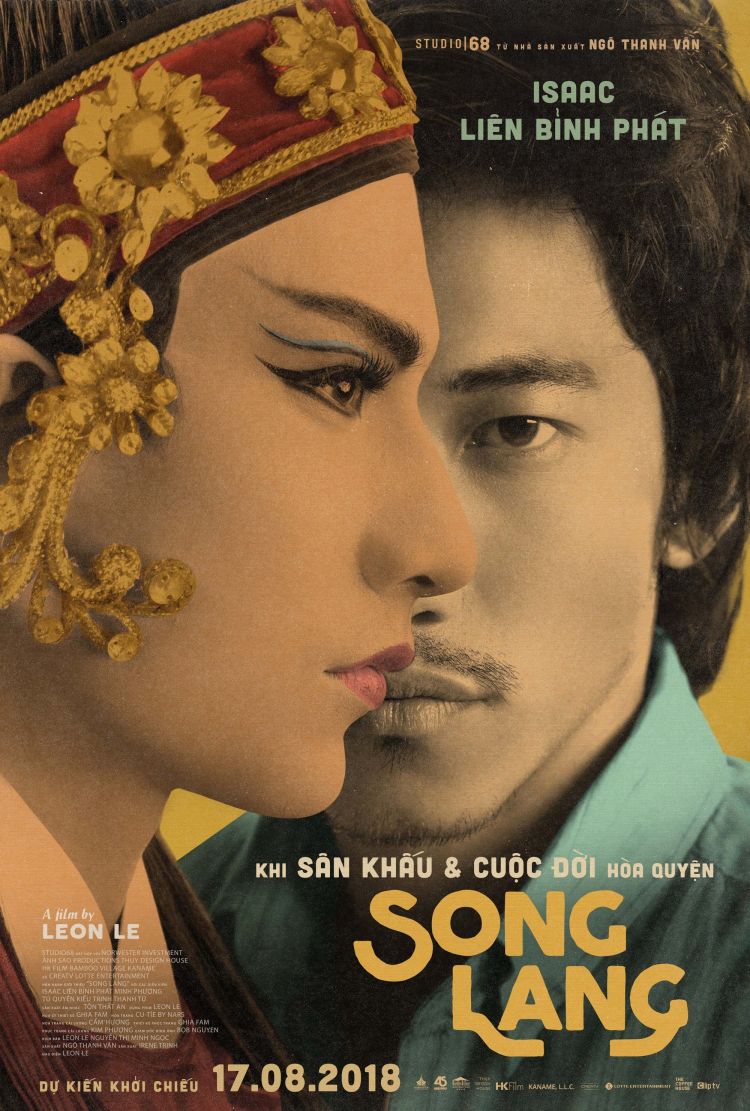

An enforcer for the steely “Auntie Nga” (Phuong Minh), Dung Thunderbolt (Lien Binh Phat) has long been trying to take revenge on his unhappy life through the intense act of self-harm which is his way of living. A routine job, however, jolts him out of his inertia when he wanders into a theatre where a cải lương opera company is preparing for a performance. There he finds himself catching sight of the famous performer Linh Phung (Isaac), only to run away, in flight from the intensity of being woken from his reverie. Later he returns to claim the debt, threatening to burn the company’s precious costumes until Linh Phung arrives and interrupts him, proudly insisting he will pay the balance after the first performance. Dung leaves confused, refusing to accept the watch and necklace that Linh Phung offered in partial payment.

A second chance meeting confirms that the two men might have more in common than they’d first assumed. The lonely Linh Phung, eating alone in a nearby cafe, gets into a fight with some drunken louts who wanted him to sing a few tunes, but as surprisingly handy as he turns out to be quickly gets himself knocked out at which point Dung steps in to rescue him, eventually taking him home to sleep it off where they later bond through a shared love of violent video games. An opportune power cut allows the two men to enter a greater level of intimacy during which Dung begins to re-embrace his cải lương childhood through the instrument his father left behind.

The Song Lang, as the opening informs us, is an embodiment of the god of music delivering the rhythm of life and guiding musicians towards the moral path. That’s a path that Dung knows all too well that he has strayed from and is perhaps looking to return to. The central theme of cải lương is “nostalgia for the past” – something echoed in Linh Phung’s peculiar philosophy of time travel through people, objects, and places which seems to be borne out in Dung’s constant flashbacks to a more innocent age before his happy childhood ended in parental betrayal and sudden abandonment.

Linh Phung, meanwhile, is nursing his own wounds. His mentor tells him that though he is popular his performance lacks depth because he lacks life experience while his co-star mocks him for never having been in love. Rooting through Dung’s belongings, he discovers a book he’d loved in childhood about a lonely elephant taken away from his jungle and sold to a circus. Both men are, in a sense, exiles from their pack walking a lonely path of confusion and despair but finding an unexpected kindred spirit one in the other as they search for new, more fulfilling ways of being. Bonding with Dung opens new emotional vistas for Linh Phung which allow him to perfect his art, while reconnecting with his childhood self through Linh Phung’s music gives Dung the courage leave his nihilistic life of shady moral justifications behind.

Fate, however, may have other plans and karma is always lurking. Linh Phung’s claim that an artist must know great grief proves truer than he realised, but it’s another passage from the book with which he eventually leaves us, affirming that it’s best to learn to enjoy these present moments rather than lingering in an unchangeable past. Yet the art of cải lương is itself steeped in nostalgia, perfect for a “time traveller” like Linh Phung returning to his sadness through his art, proving in a sense that the past is always present and wilfully inescapable. A melancholy, romantic evocation of Saigon in the 1980s, Song Lang is also a beautifully pitched paen to a fading art form and an “unfinished love song” to lost lovers in which two lonely souls find an echo in each other but discover only tragedy in the implacability of fate.

Song Lang screened as part of the 2019 New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (Vietnamese subtitles only)