“Getting others to trust something is more important, not what they choose to believe” advises a cynical politician a little way into Lee Su-jin’s Idol (우상, Woosang). Image is indeed everything. Who are you more likely to believe – the slick, seemingly upstanding politician who’s done everything “right”, or an ageing, inarticulate aircon repairman with bleach blond hair? Two fathers go to bat for their sons, if in very different ways, but only one can emerge “victorious” in their strangely symmetrical endeavours.

“Getting others to trust something is more important, not what they choose to believe” advises a cynical politician a little way into Lee Su-jin’s Idol (우상, Woosang). Image is indeed everything. Who are you more likely to believe – the slick, seemingly upstanding politician who’s done everything “right”, or an ageing, inarticulate aircon repairman with bleach blond hair? Two fathers go to bat for their sons, if in very different ways, but only one can emerge “victorious” in their strangely symmetrical endeavours.

Lee opens with a voice-over taken from a speech later in the film belonging to bereaved father Yoo (Sol Kyung-gu) in which he confesses that as his son Bu-nam (Lee Woo-hyun), who had severe learning difficulties, grew older, he found himself having to masturbate him to prevent him harming himself trying to calm his sexual urges. Yoo’s words play over his opposite number’s return home from a research trip to Japan. Koo (Han Suk-kyu) is a politician and former herbalist with a special interest in nuclear power. Ambitious, he spends much of his time travelling for business while his wife (Kang Mal-geum) cares for their wayward adolescent son, Johan (Jo Byung-gyu). A panicked text message warning that Johan has got himself into trouble again gets ignored, but when he arrives home Koo knows he has to act. Johan has knocked someone over and rather than take them to hospital, he’s brought the body back home.

A series of quick calculations tells him that the “best” option is for Johan to turn himself in, despite his wife’s insistence that they simply get rid of the body. He drives the corpse back to the scene and dumps it, gets rid of the original car, and then drives his son to the police station before expressing contrition in front of the cameras. That would have been that if it weren’t for Yoo’s dogged determination to find out what happened to his boy, and the fact that Bu-nam’s “wife” Ryeon-hwa (Chun Woo-hee), an undocumented former sex worker from China, managed to escape meaning there are loose ends Koo knows he needs to tie up.

“This rotting smell” Ryeon-hwa exclaims on putting a number of things together. There is something undoubtedly corrupt in Koo’s superficially smooth world of neatly pressed suits and sharp haircuts. Stagnant water swells around him, along with a murky swirl of blood, as he contemplates the best way out of his present predicament. Everything here is stained, marked, or scarred as if hinting at the darkness beneath gradually seeping through.

Yoo, meanwhile, perhaps knows he lives in a “dirty” world and though he never claims to be completely clean himself, is fully aware of the implications of his actions. A widowed father, he tried to do the best for his disabled son. He offered him relief in ways others would find perverse in a strange gesture of fatherly love, finally deciding to get him a wife in the hope of putting an end to such degradation for them both only to regret his decision when he realises Bu-nam may not have died if he’d just stayed home. Koo, meanwhile, tries less to protect his son than himself, weighing up that the boy will most likely get a slap on the wrist and he’ll come out of it looking better because he behaved “honestly” and in line with the law. To get elected he will stop at nothing to preserve the image of properness, even if it means he must get his hands “dirty”.

In that essential ruthlessness, he may have something in common with the jaded Ryeon-hwa whose sister warns Yoo not to trust her because “her nature is different”. Like Koo, she has done terrible things but done them to survive rather than to prosper. Her marriage to Bu-nam might seem like no prize, but it was better than the life she was leaving behind and, crucially, a guaranteed path to Korean citizenship assuming Yoo eventually filled in the marriage papers properly.

Yoo just wants “justice”, but ruthless men like Koo who care about little other than image are not about to let him get it, which is why he finds himself trotted out as a superficial ally to bolster Koo’s appearance at the polls in return for Ryeon-hwa’s “assured” safety. In the end, all Koo’s scheming blows up in his face, but, Lee seems to say, the image always survives and men like Koo know how to spin it to their advantage while men like Yoo will always be at the mercy of the system. A bleak, often confusing, noirish thriller, Idol plunges a knife deep into the heart of societal corruption but finds that truth often matters less than the semblance of it in a society which idolises the superficial.

Idol was screened as part of the 2019 Fantasia International Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

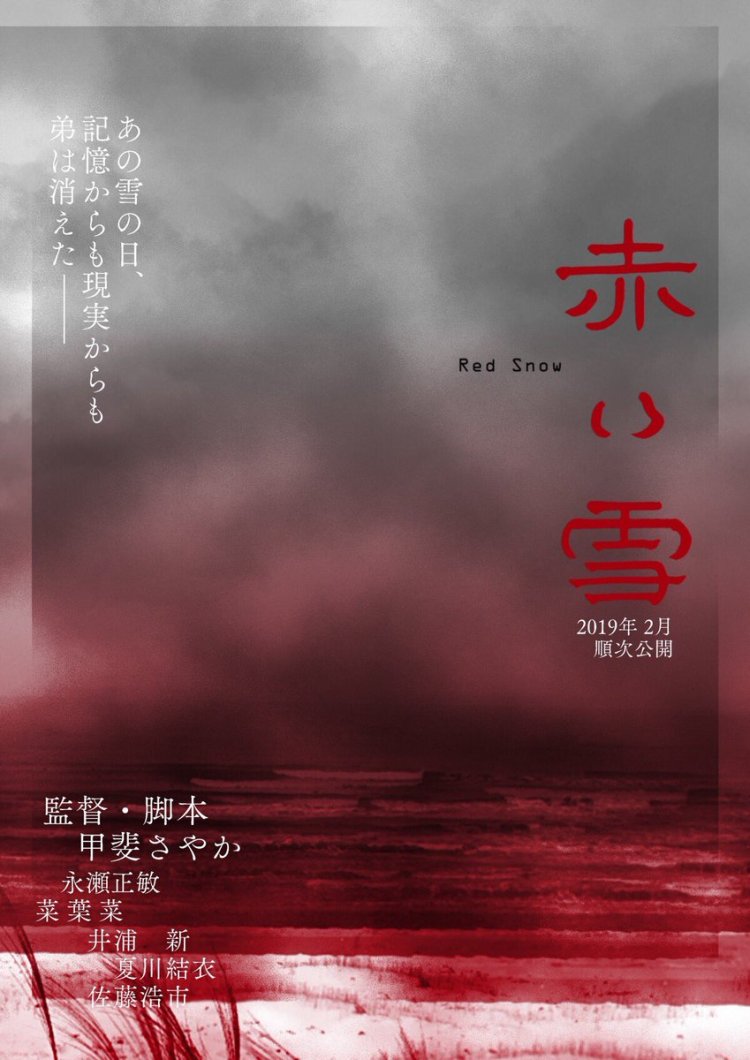

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.

“We’re just pieces of a puzzle” a temporarily deranged woman exclaims to a gloomy seeker after truth in Sayaka Kai’s eerie debut Red Snow (赤い雪, Akai Yuki). Truth, as it turns out is an elusive concept for these variously troubled souls trapped in a purgatorial tailspin on their gloomy island home. When a stranger comes to town intent on unearthing the long buried past, he stirs up deeply repressed emotion and barely concealed anger but finds himself floundering in the maddening snows of a possibly imaginary coastal village.