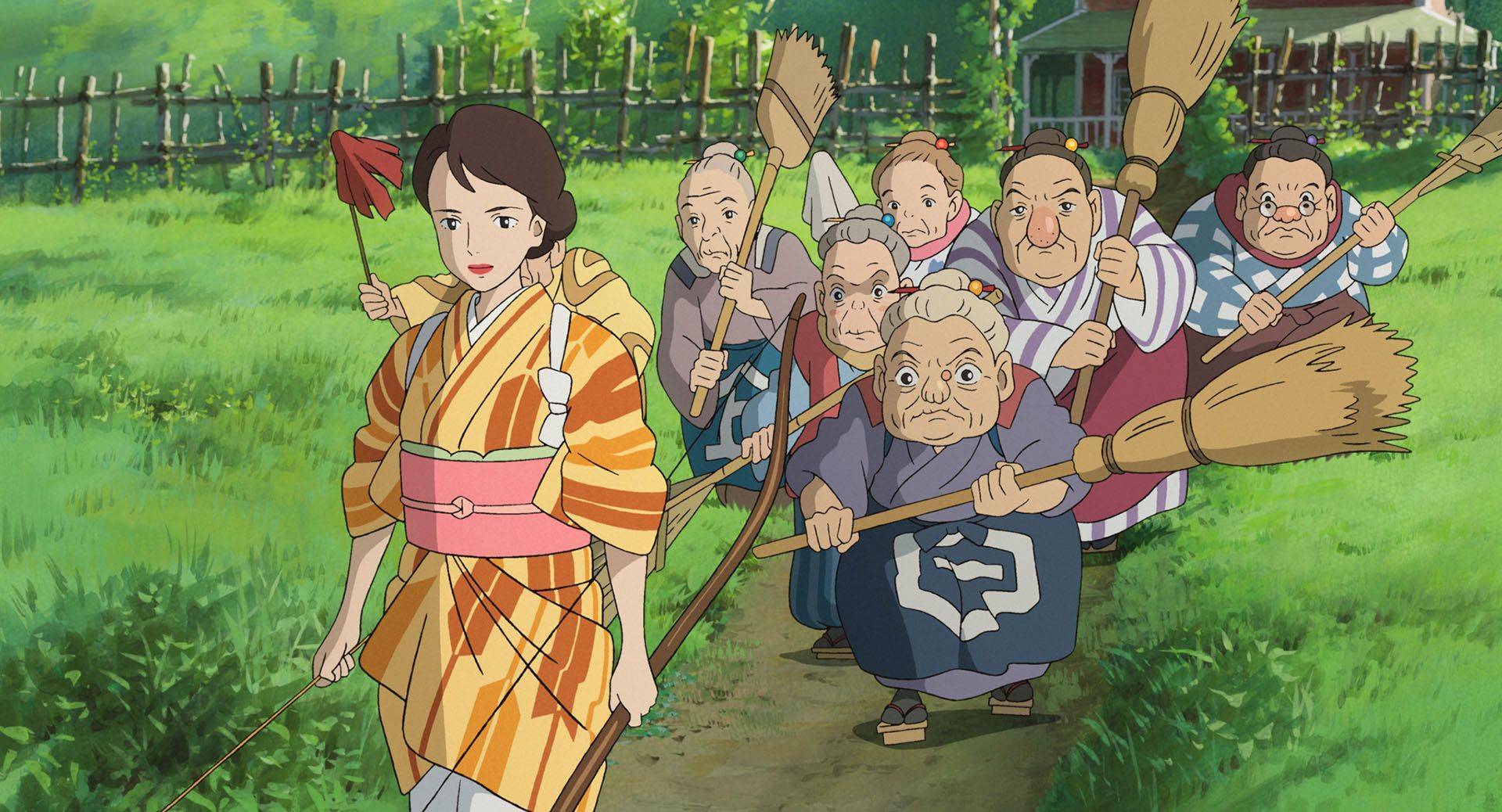

An earnest young man does everything he can to try and impress his traditionalist father-in-law-to-be but just can’t seem to catch break in Yi Xiaoxing’s charming road trip comedy, Godspeed (人生路不熟, rénshēnglùbùshú). Seemingly a representative of contemporary youth who find themselves facing pressure from above with not only disapproving parents but exploitative bosses breathing down their necks, Yifan (Fan Chengcheng) is a classic mild mannered guy who’s been beaten down and bullied all his life but finally finds the courage to stand up for himself while battling to prove his worth to his girlfriend’s dad.

The reason Donghai (Qiao Shan) objects to Yifan is at heart the obvious one that he can’t really accept the idea of his daughter getting married and in the end no man will ever be good enough to change his mind. But it’s also true that truck driver Donghai is an old fashioned man’s man with very strong ideas of traditional masculinity that Yifan is never going to live up to. Tall, skinny, and a glasses wearer, Yifan is a programmer at a games studio where he’s exploited by their smarmy boss who instantly turns down the game he’s made himself and tells him to pirate the latest successful games from other companies and rip them off instead. His problem is that Donghai thinks games are “immature” so his girlfriend Weiyu (Zhang Jinyi) has advised him to be economical with the truth when her father inevitably asks about his career prospects.

It has to be said that it’s not practical to lie about something as fundamental as a job when you’re intending on forging a longterm relationship with someone, but Yifan is very focussed on the present moment and at least making a good impression on Donghai so that he’ll accept him as a son-in-law. In fact, Yifan hasn’t actually proposed yet and was planning on doing it after meeting the parents and attending the 80th birthday celebrations of Weiyu’s grandfather but things get off to a bad start when he accidentally locks Donghai in a butcher’s freezer after minor misunderstanding causing him to become fused with some giant slabs of pork. Donghai doesn’t like his “childish” fashion sense, so Yifai switches to smart shirts and trousers to try to please him but is never really sure if Donghai appreciates the way he’s changing to live up to his idea of “maturity” or in fact thinks less of him for it in his infinite desire to please.

“You’re going the wrong way,” Weiyu’s mother Meimei (Ma Li) tries to tell Donghai in a more literal sense as she and Weiyu end up taking their car with Yifan and Donghai in the truck because Donghai insisted there wasn’t enough room for Yifan and the family dog. Donghai is afraid that Weiyu will “go the wrong way” with a man like Yifan, but is also going down a dangerous road himself in refusing to accept that his daughter has grown up and can make her own decisions as regards her romantic future. He wanted her to marry childhood friend Guang (Chan Yuen) who has since become incredibly wealthy, but even he is later exposed as a poser who has also “lied” about his financial circumstances in what seems to be an ongoing rebuke of the obnoxious superrich also exemplified by Donghai’s arrogant frenemy and his high tech caravan not to mention spoilt grandson with a Western name.

Yet what Yifan comes to realise is that there is no “right way” except his own and it’s time for him to stop simply accepting the injustices of the world around him as Donghai has also been doing in appeasing a gang of petrol thieves who’ve been terrorising trucker society for the last few years. Together, they each begin to break free of their decade’s long inertia, Yifan deciding to be his own man and a “company owner” after all and Donghai embracing the freedom of retirement and the open road on going on a second road trip honeymoon with Meimei. The older generation has to learn to let the other one go, stepping back and getting out of the way of their children’s happiness, while simultaneously regaining a kind of independence to start a new life of their own. Flat out hilarious in its improbable mishaps but also poignant and heartfelt in its central relationships, the film’s zany sense of optimism and possibility become a winning combination as Yifan discovers the courage to step into himself and be his own man no longer beholden to a bullying society.

International trailer (Simplified Chinese / English subtitles)