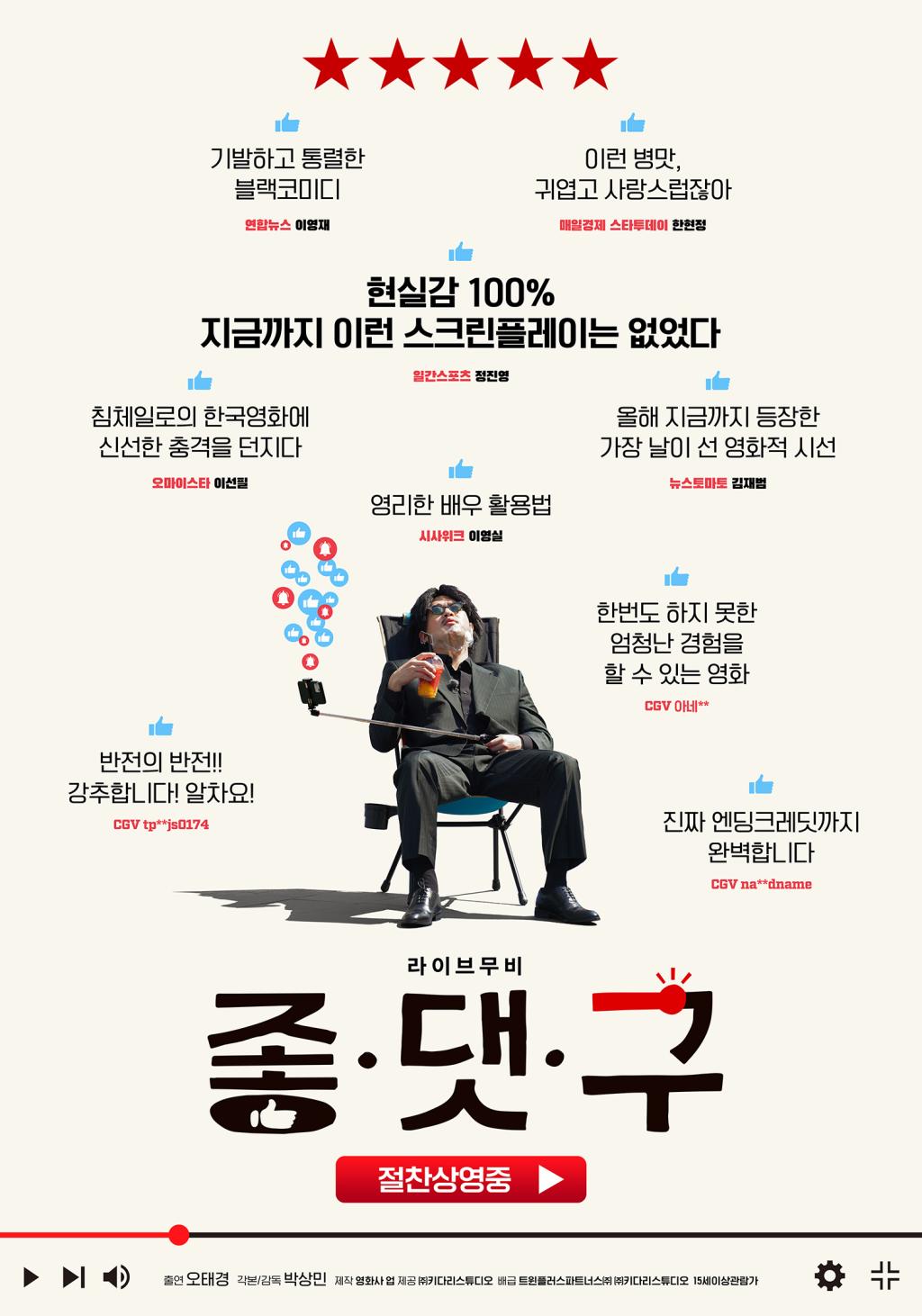

The central irony of Park Sang-min’s meta comedy I Haven’t Done Anything (좋.댓.구, Joh.Daes.Gu) is that a man who remains defiantly silent generates much more interest than the one desperately chasing YouTube success. Adopting a “screen life” aesthetic in which much of the action is told through social media and video screens, the film asks a series of questions about our petty obsessions, online authenticity, media manipulation, and the impossibility of escaping a predetermined image as its embattled hero strives to reinvent himself by his inhabiting most famous role.

Actor Oh Tae-kyung plays a version of himself who is struggling to maintain his career as an actor having begun as a child star with his most high profile roles including that of the younger Oh Dae-su in Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy. With work thin on the ground, he turns to YouTube but fails to make an impact with content that commenters describe as old hat such as “mukbang” eating videos and unboxings. It’s then that he comes up with the idea of rebranding as “Li’l Oh Dae-su”, dressing up as the protagonist of Old Boy and accepting viewers’ challenges which at one point include him taking revenge on a gang of class bullies by hitting them on the head with a plastic mallet while mimicking the famous corridor fight scene from the landmark drama.

But then, someone else has already shared their screen with us. Going under the name “Bulldog”, a viewer asks Tae-Kyung to solve the mystery behind a man who’s been standing silently in the square with a large sign reading “I Haven’t Done Anything”. Tae-kyung reasonably wonders why Bulldog didn’t just ask the guy himself, but as he explains “Picket Man” refused to answer him. Given the large amount of money Bulldog has pledged for this seemingly simple request, Tae-kyung accepts the challenge but Picket Man continues to ignore him no matter the silly stunts he pulls an attempt to break his concentration.

Bulldog’s apparently strong desire to know the truth, willing to offer up vast sums of money just to satisfy his curiosity, hints at our own petty obsessions. After all, the cryptic quality of the sign is intriguing. What exactly is Picket Man trying to say, what didn’t he do and who says he did it? Of course, in another way, Tae-kyung also feels he hasn’t done “anything” with his life and stuck in a career morass unable to shed the image of himself as a child actor and young Dae-su in particular. Every time someone offers him another role, he worries that the baggage of his early career follows him and he’s simply not credible as a hardened gangster, for example, if everyone only sees him as the eldest of six siblings in a much loved TV drama or the little boy who grow up to become the schlubby captive Oh Dae-su.

When the skit becomes an accidental viral hit, Tae-kyung begins to worry that perhaps he’s doing Picket Man a disservice and this kind of publicity isn’t really what he was after though it’s puzzling that he himself refuses to speak about what it is he hasn’t done. What he realises is that Picket Man is much like himself and he’s done to him what others have done to Tae-kyung in reducing him to a single image. How will anyone ever see this otherwise anonymous person as anything other than “Picket Man” now? Tae-kyung has unwittingly exploited him for his own ends and possibly ruined his life in the same way that anyone who becomes a meme is robbed of an identity.

Then again, in this very meta tale not everything is as we think it is and we ourselves, like the YouTube commenters, are being manipulated by unseen forces. As Picket Man becomes the latest social media phenomenon, other content creators start arbitrarily jumping on the hashtag, randomly mentioning Picket Man to boost their own views while unscrupulous forces also exploit the meme potential to run scams featuring Picket Man’s image. Park carries the meta quality through to interrupting the film with fake YouTube ads and product placement from sponsors that remind us we are being sold something whether we realise it or not and that we might not even realise what the product is or who’s selling to us as the final reveal implies. Nevertheless, there’s a sense of triumph in the success of this heist that’s been pulled on us in the winning self-deprecation of dejected former child star Tae-kyung and his great master plan to shed himself of an otherwise inescapable image.

I Haven’t Done Anything screens 5th November as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)