Part way through Shinya Tamada’s empathetic social drama I Am What I Am (そばかす, Sobakasu), the heroine’s sister remarks that she wishes she could live as if the world did not concern her as she assumes her sister does. In many ways, it’s an incredibly ironic statement because Kasumi (Toko Miura) finds herself constantly at the mercy of a world which refuses to acknowledge her, certain that the truth she offers freely of herself must be a lie or at least a cover for some other kind of shame.

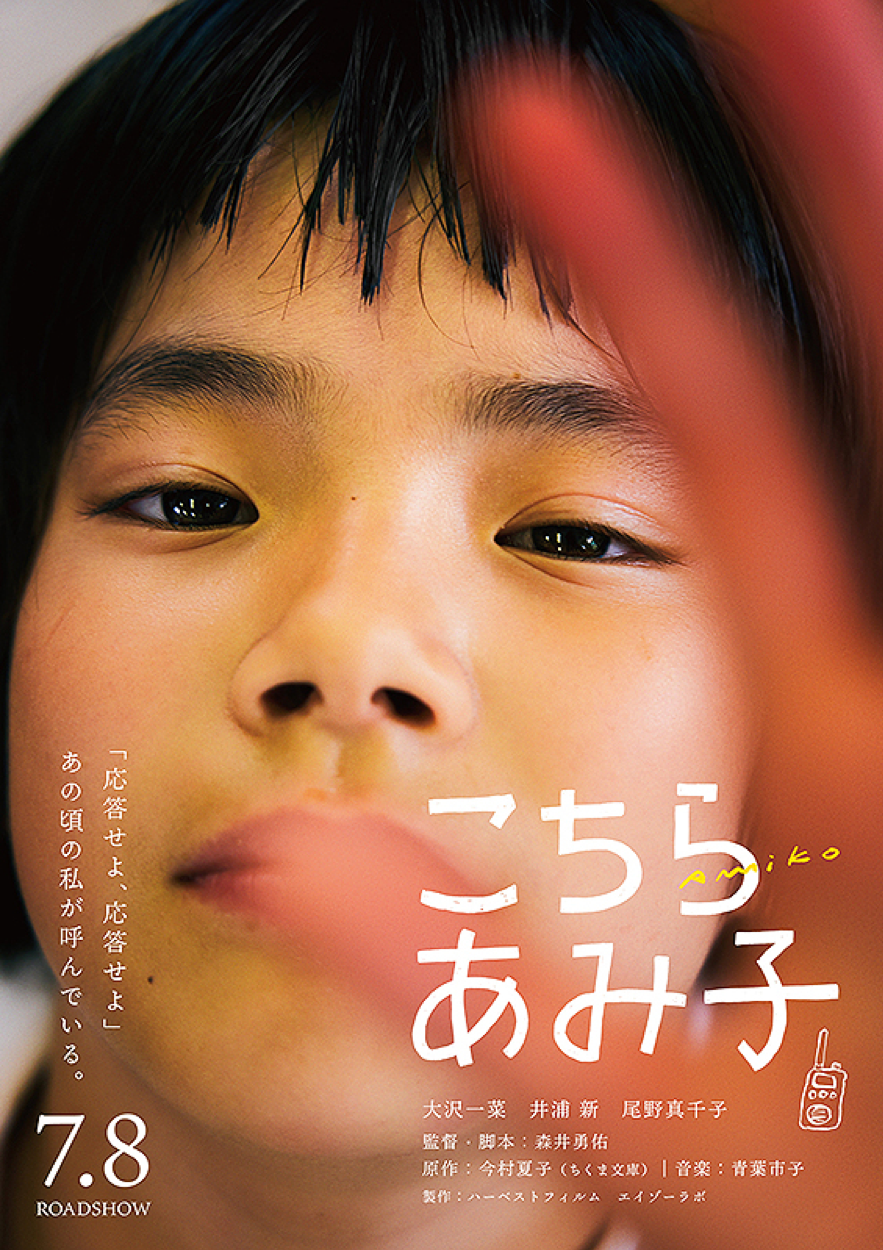

The fact is that Kasumi is asexual and has no interest in love or dating. As the film opens, she appears to be on some kind of awkward double date but seems isolated and aloof, as if deliberately left out of a conversation as she will be several times throughout the course of the film because of the centrality of “romance” in most people’s lives. She’s constantly asked about her “type”, or what she finds attractive in a man with a clear presumption of heteronormativity in also in play. Not wanting to get into it, Kasumi finds herself just nodding along offering some vague, stereotypical comment to smooth things over. When one of the men does strike up a more interesting conversation to which Kasumi can enthusiastically contribute, he doesn’t even listen to her but abruptly gets up to chase her friend. She ends up going to ramen bar on her own to decompress before running the gauntlet at home between mum, sister, and grandma who are all very confused by her lack of interest in marriage.

Kasumi’s mother tells her that she has to get married someday, unable to accept that not to do so is also valid choice. Whether she does this because she feels embarrassed to have a 30-year-old unmarried daughter fearing that it reflects negatively on her parenting, is genuinely worried that Kasumi is lonely and unable to progress romantically because of shyness, or has a practical concern that she’ll be alone when she’s old, remains unclear though it does seem that her quest to marry Kasumi off is more to do with herself than her daughter. But with grandma apparently having had three divorces of her own, Kasumi’s sister Natsumi (Marika Ito) paranoid her husband’s cheating on her while she’s pregnant, and the parents’ marriage strained by her father’s depression it’s only natural she may wonder what’s so great about marriage anyway.

In any case, though Kasumi constantly tells people quite directly that the issue is she has never experienced romantic desire and is fine the way she is they refuse to believe her assuming either that she is shy, stubbornly rebellious, or as her sister later suggests, gay. “No one would judge you for that,” she spits out less than sympathetically even while quite clearly judging her for this, as if it denies a basic fact of biology as unthinkable as someone claiming not to breathe the air. Her friend, Yashiro, who introduces her to a new job at a kindergarten, reveals that people did indeed judge him for being gay which is why he’s returned to his hometown. Not even he really believes Kasumi though eventually develops a sense of solidarity with her when her attempt to update Cinderella for a new, more inclusive generation leaves her both exposed and humiliated with a conservative politician visiting the school remarking that he thinks “diversity” is all very well but it only confuses the children and perhaps they should learn about it after developing “solid values”.

The irony is that Kasumi is remarkably unjudgemental and accepting of all those around her, Yashiro remarking that he just knew she would be a safe person to disclose his sexuality to while she also bats nary an eyelid on reconnecting with a middle school friend (Atsuko Maeda) who turns out to have become a famous porn star in Tokyo only keen to protect her from the unwanted attention of star struck teenage boys and the accusatory eyes of those around them. Each of her attempts to find platonic friendship also fails because sooner or later romance gets in the way. She hits it off with the guy at the omiai marriage meeting her mother tricked her into attending because he also reveals that he has no desire to date or get married, but as much as she thinks she’s found a kindred spirit it turns out that his issue was a more conventional reluctance to enter a serious relationship. When he develops feelings and she has explain again that she meant it when she said she had no interest in romance he takes it personally, insisting that she’s lying and resentful that she doesn’t find him attractive. An attempt to get a flat with a female friend also hits the rocks when she decides to get back together with an ex instead.

When questioned about dating activities and giving the unoriginal answer of the cinema, Kasumi had mentioned a fondness for Hollywood remake of the War of the Worlds starring Tom Cruise. She later elaborates on her statement that she likes the way he runs to explain that in most of his other films, Tom Cruise is usually running towards something but in this one he’s just a regular guy running from trouble which something she can relate to because she’s been running away all of her life too. Yet the unexpected discovery that her mini stand over Cinderella might have done some good after all along with encountering someone who might indeed be a kindred spirit gives her the courage to start moving forward, less concerned by the world and more confident in herself. An empathetic tale of one woman’s attempt to live her life the way she wants frustrated by a conformist society, Tamada’s gentle slice of life drama is a refreshingly empathetic in its fierce defence of its heroine’s right to chase happiness in the way that best suits her.

I Am What I Am screened as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Images: ©2022 “I am what I am” film partners