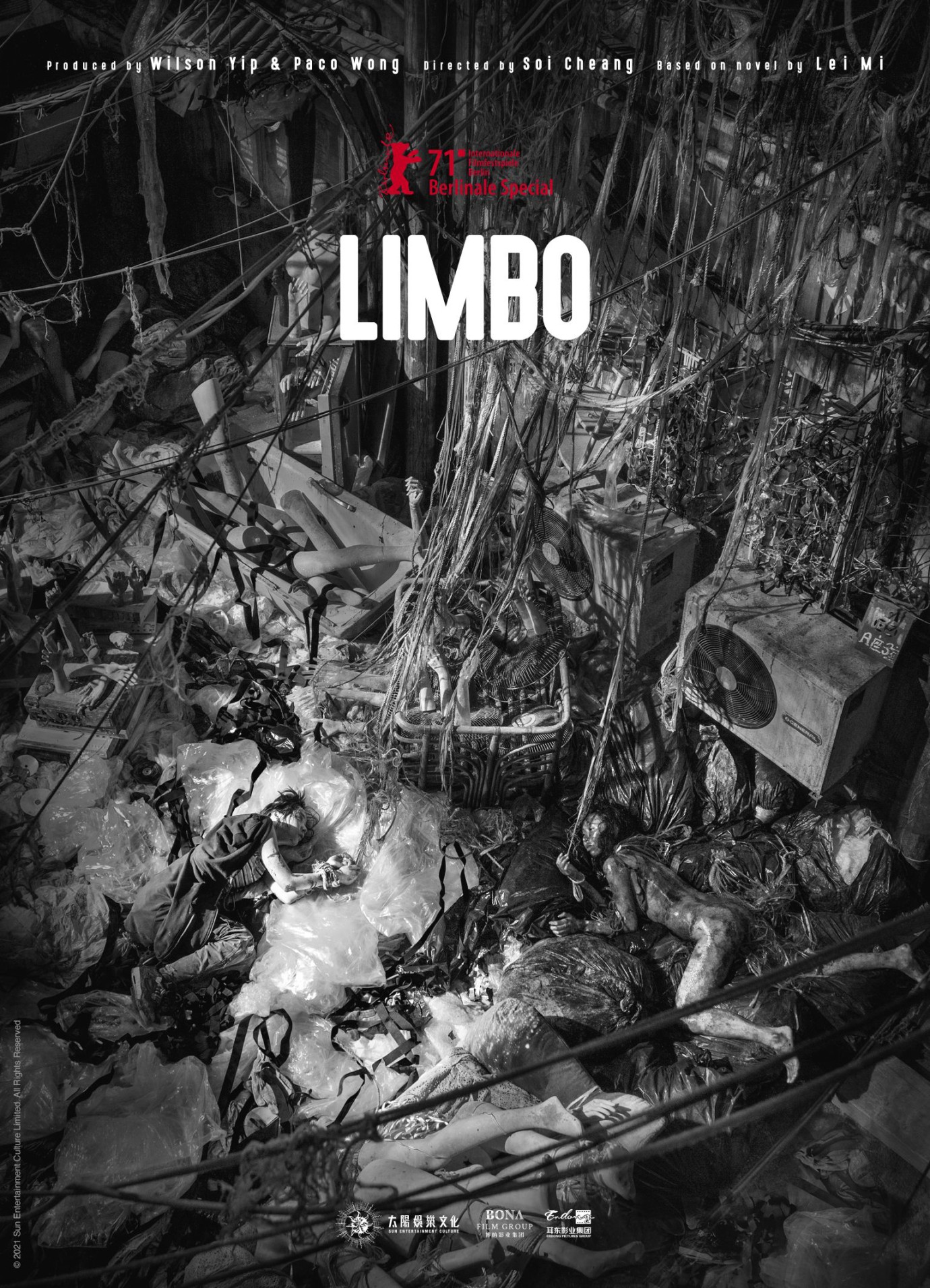

“I forgive you. Please live well”, a final message from the dying to one attempting to survive the junkyard hellscape of contemporary Hong Kong. Soi Cheang’s stylish thriller Limbo (智齒), shot in a high contrast monochrome lending the city state the rain-soaked aesthetic of cyberpunk noir, is in many senses a purgatorial odyssey as its pregnant title implies sending its duo of morally compromised cops into a world of the dispossessed inhabited by those “thrown away” by their society and thereafter left to rot among the detritus of an uncaring city.

Hong Kong’s homeless may occupy a liminal space, trapped in an inescapable limbo, but it’s grizzled cop Cham (Gordon Lam Ka-tung) who is the most arrested, unable to move on from the accident which left his pregnant wife suspended in a coma. To escape his own sense of purgatorial inertia, he seeks closure in chasing down petty criminal Wong To (Cya Liu) whom he holds responsible for his fate on discovering she has been granted early parole for good behaviour. As fate would have it, Wong To’s release back into the underworld (after all, where else was she to go?) has unexpected connection to the case Cham is currently investigating in the mysterious appearance of random severed hands each belonging to “social outcasts”, as Cham’s slick rookie partner puts it, they fear may hint at the existence of a serial killer growing in confidence.

Adapted from a novel by Lei Mi, the film’s Chinese title is simply “Wisdom Tooth”, a tongue in cheek reference to the ongoing toothache which places cop two Will Ren (Mason Lee) in his own kind of purgatorial pain, the offending molar eventually knocked out during his climactic fight with the killer during which he will in a sense transgress, passing from innocence to experience in gaining the wisdom that police work’s not as black and white as he may have believed it to be. “Cops are human too” his boss reminds him as he takes the controversial step of reporting his new partner for inappropriate use of force while pursuing a personal vendetta not exactly connected with his current case. He doesn’t disagree, but points out that police officers have guns and are supposed to uphold the law, not abuse their authority and take it into their own hands.

But then, who is really responsible for the junkyards of the modern city and their ever increasing denizens abandoned by a society which chooses to discard them along with all their other “rubbish”, little different from the dismembered mannequins which people the killer’s eerie lair. Soi frequently cuts back to scenes of the dispossessed often looking stunned or vacant as they sit on mattresses or abandoned sofas surrounded by the pregnant disrepair of a city in the midst of remaking itself as if they were sitting on skin in the process of being shed by a slow moving snake. It would be tempting to assume the killer has a vendetta against “social outcasts”, his victims sex workers, drug users, and criminals though in truth these people are simply the most vulnerable even if there is no clear motive provided for the crimes save a minor maternal fixation and possible religious mania. A drug dealer ensnared by Cham’s net remains loyal to the killer, “We’re not as crazy as you. We are rubbish, so what? In this world, he’s the only one who cares.” she tells him, unwilling to give up her one source of connection even while aware of her constant proximity to death and violence.

Cast into this world, Wong To too is trapped in an individual purgatory longing for forgiveness for her role in the death of Cham’s wife, a forgiveness he cruelly denies her even while making use of her desperation to force her to risk her life for him in betraying her underworld contacts to edge towards the killer. “Why are you treating me like this?” she asks, “I don’t want to die”, well aware that denied his direct vengeance by Will Cham is attempting to kill her by proxy. Wong To keeps running, keeps fighting, refuses to give up while seeking atonement and an escape from this broken world of violence and decay. It is she who eventually holds the key to an escape from purgatory, the cycle is ended only in forgiveness. Soi’s stylish drama may paint the modern society as a venal hellscape neglected by corrupt authority, but nevertheless permits a final ray of light in the possibility of liberation through personal redemption.

Limbo streams in Europe until 2nd July as part of this year’s hybrid edition Udine Far East Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)