Shikoro Ichibei (Tomisaburo Wakayama) returns yet this time seemingly on the opposite side in the second in the Bounty Hunter series, The Fort of Death (五人の賞金稼ぎ, Gonin no Shokin Kasegi) this time directed by Eiichi Kudo. If the first film had been an Edo-era take on James Bond, the second is very much Spaghetti Western and feudal tragedy as Ichibei finds himself coming to, if not quite the rescue of the oppressed farmers, then at least moral support in taking stand against corrupt and self-interested lords.

This might be surprising in that in the first film Ichibei had been a shogunate spy and seemingly close friend of the man himself, yet this time around he’s working as a doctor while taking bounty hunter jobs to earn extra money to support the poor people who come to him for help. Like a true western hero, he has a small posse which includes the ninja lady, Kagero (Tomoko Mayama), from the first film only she’s being played by the actress who previously starred as his other love interest. In any case, he’s approached by a young man from a small village which is making a last-ditch appeal to the local lord to lower their tax burdens so they don’t all starve, though so far the lord’s response has been to add additional taxes and kill people for not paying them.

On his arrival, Ichibei soon realises that the man who recommended him was actually the leader of the government forces during a previous peasant uprising at which Ichibei had also tried to help the farmers. In that case, Bessho (Shin Tokudaiji) had won, but it didn’t do him any good. His clan was dissolved and he became a wanderer, taken in by the village and now indebted to them, hoping Ichibei can help but fully aware of the brutality with which such challenges to the feudal order are put down.

The lord later suggests it’s not really his fault. He has to curry favour with Edo to protect the domain, which is why he agreed to participate in a construction project that led him to confiscate all of his farmers’ rice and wheat. But then it’s also true that he is vain, and cruel. On realising the village has hired a man like Ichibei, some of the retainers suggest reopening negotiations but others complain that they must now crush the farmers or face ruin themselves while trying to ensure the strife in their domain does not come to the attention of the government in Edo.

Part of their problem is that Ichibei simply has better technology in the form of gatling guns. Tying into the western themes, Ichibei is well versed in the use of firearms, while the samurai are mostly reliant on traditional weaponry such as arrows and swords. The lord later insists on using some canons, but is oblivious to the risk as the shogun has banned the use of gunpowder and using them may end up bringing him to his attention and thereby landing him in a lot of possible fatal trouble.

In any case, it’s the villagers who suffer. Ichibei encounters a woman who has lost her mind, refusing to give up her baby who has died of malnutrition while her husband was executed for non payment of taxes. Meanwhile, some of the other ronin they hired attempt to rape a villager, and a young couple are prevented from marrying because the headman is worried that it would send the wrong message in a time so much strife. Then again, a woman basically attempts to rape Ichibei, descending on him while he’s still asleep which otherwise leads into a fairly comic sequence in which Ichibei must fight of a bunch of ninjas intent on stealing the gatling gun while dressed only his underwear.

Darkly comic it may be, but also surprisingly violent with a ninja at one point using a dead body as a Molotov cocktail not to mention the severed heads and limbs of the battle scenes. Ichibei is fully aware that the battle is a forlorn hope, but also that the villagers have no choice and perhaps this is better for them than simply accepting their fate and starving to death. Even so, he reserves his final words for the Edo inspector who arrives only when the battle is done to survey the scene, berating him that he ought to know what happened here from looking at the battlefield and deducing that this domain has not been run particularly well. It’s a tragedy of feudalism that provokes a tearful rage from the compassionate bounty hunter trying his best to heal the sickness in his society, though perhaps like the patient who visits him with a venereal complaint concluding the best solution is to cut it right off.

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

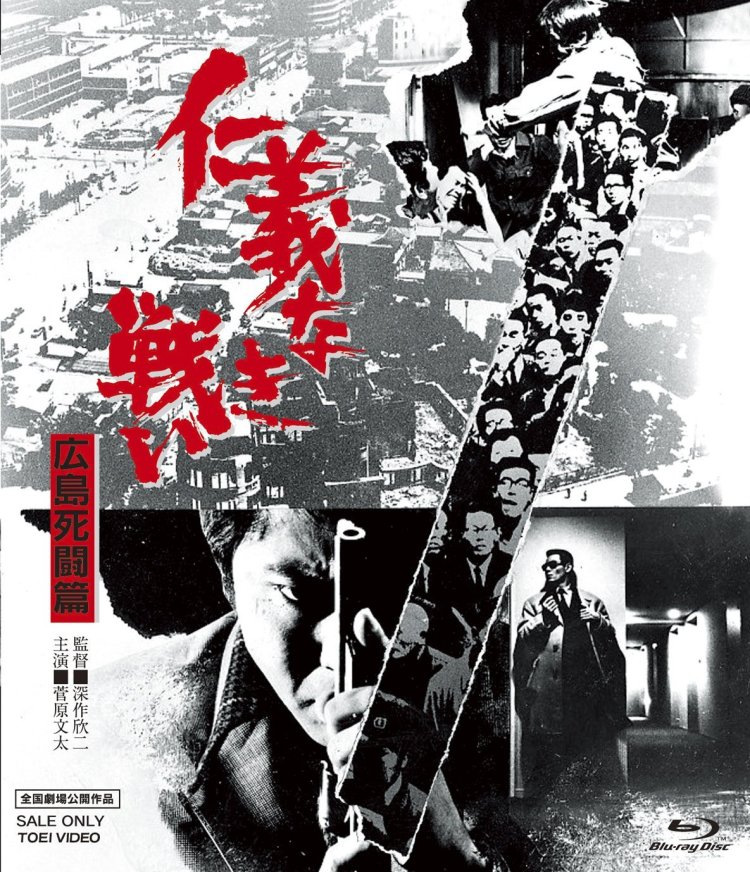

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly. If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of

If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of