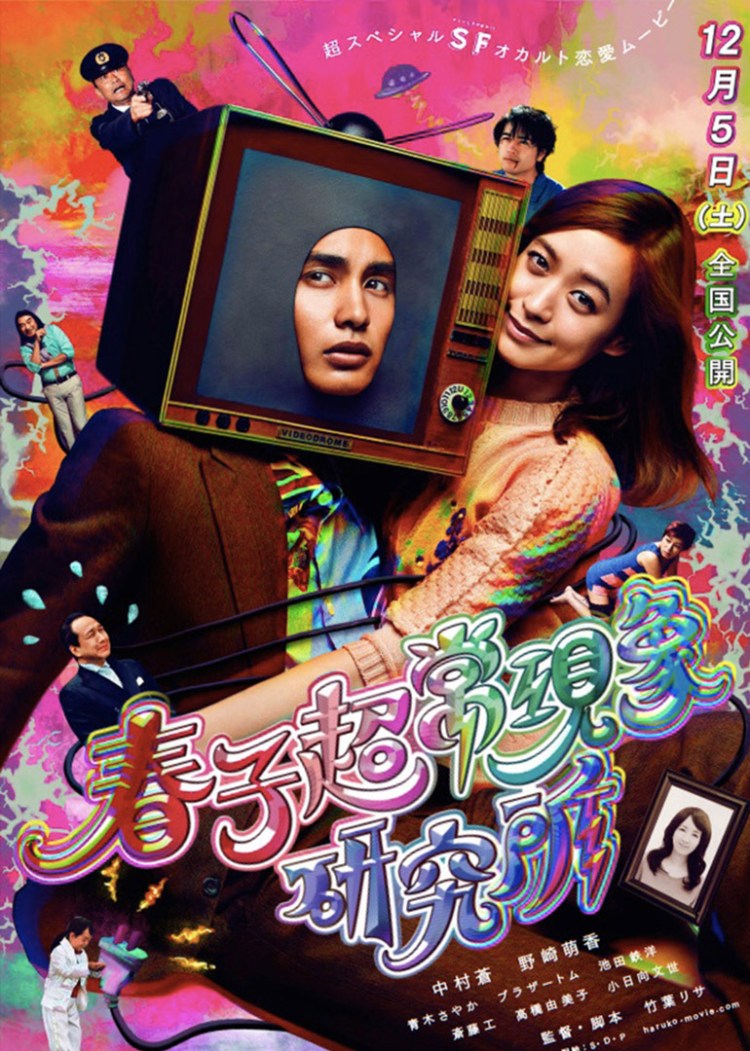

In the brave new Netflix era, perhaps it’s not unusual to hear someone exclaim that their most significant relationship is with their television, but most people do not mean it as literally as Haruko, the heroine of the self titled Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory (春子超常現象研究所, Haruko Chojogensho Kenkyujo). Lisa Takeba returns with her second film which proves to be just as strange and quirky as the first and all the better for it. Haruko’s world is a surreal one in which a TV coming to life is perfectly natural, as is the widespread plague of “artistic” behaviour which involves robbing the local 100 yen store for loose change and randomly setting fire to things. Yet Haruko’s problems are the normal ones at heart – namely, loneliness and disconnection. Takeba’s setting may be a strange fever dream filled with fiendishly clever, zany humour but the fear and anxiety are all too real.

In the brave new Netflix era, perhaps it’s not unusual to hear someone exclaim that their most significant relationship is with their television, but most people do not mean it as literally as Haruko, the heroine of the self titled Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory (春子超常現象研究所, Haruko Chojogensho Kenkyujo). Lisa Takeba returns with her second film which proves to be just as strange and quirky as the first and all the better for it. Haruko’s world is a surreal one in which a TV coming to life is perfectly natural, as is the widespread plague of “artistic” behaviour which involves robbing the local 100 yen store for loose change and randomly setting fire to things. Yet Haruko’s problems are the normal ones at heart – namely, loneliness and disconnection. Takeba’s setting may be a strange fever dream filled with fiendishly clever, zany humour but the fear and anxiety are all too real.

As a teenager, Haruko (Moeka Nozaki) was something of a loner. Being the daughter of a teacher and having a strong interest in UFOs and other supernatural entities, she had few friends and longed for something “exciting” to happen. Sadly, something quite exciting did happen, but it involved a suicide and her brother apparently being abducted by aliens. Ten or fifteen years later, Haruko still maintains her “Paranormal Laboratory” and intense interest in aliens with a view to maybe finding out what happened to her brother, but her external life is less satisfying. Her main hobby is lying around watching her 1950s black and white CRT TV and swearing loudly at the ridiculous images it projects. Her TV, however, has finally had enough and upon hearing 1000 dirty words from Haruko, springs into life as a handsome young man with telebox for a head.

An usual genesis for a relationship, but then when you spend all of your spare time googling paranormal events and harping on your teenage failures, beggars can’t be choosers. Haruko’s growing relationship with TV (Aoi Nakamura) follows the classic amnesiac mould as the two begin living together and eventually become an odd kind of couple. TV’s central operating system is pulled together from what he’s observed over the airwaves which means he has a slightly less realistic view point than your average guy. Though originally content to fall into the stereotypically “female” role, staying home cooking meals and tidying up while Haruko goes to work, he soon becomes depressed out of boredom and loneliness before eventually being made to feel inadequate when someone refers to him as a “freeloader”. Like many a spouse whose decision to stay home has not been entirely their own, TV has a lot of skills including the ability to speak 12 languages fluently, but what finally gets him a job as a TV star (yes, a TV on TV!), is his sex appeal and exotic appearance.

TV also thinks he can remember his “family” which lends a bittersweet dimension to his relationship with Haruko as she helps him look for the wife and child that might be waiting for him. Haruko’s relationship with her own family is strained. Complaining that her family are “annoying” she leaves her well meaning father standing on the doorstep when he’s come out of his way to deliver some of her favourite cup cakes which he’s baked for her himself. Haruko’s mother has since passed on but her feeling of familial disconnection stems right back into her childhood and one strange UFO hunting night during which she discovered something about her brother which may explain his long term absence. This potentially rich seam is merely background to Haruko’s life (something which she later realises as she figures out that her brother may have been watching over her in disguise all these years), but that her brother has felt the need to hide himself away following a traumatic childhood incident is certainly a sad mirror for Haruko’s own ongoing psychological isolation.

Takeba piles jokes on top of jokes in this strange world where ‘50s “Videodrome” TVs with Yubari Film Festival tags still work and play adverts in which cheap whiskey “for the needy” is advanced as a good father’s day present, and an idol retires from the top band KKK48 live on air. Freak shows, extreme cosplay, marital disconnect, “artistic” robbery and arson, and a very dedicated NHK man, pepper the scene but the outcome is a young woman stepping away from her romantic fantasies towards something more real, realising she doesn’t really need to meet aliens so much as she needs to pay more attention to the “normal” world. Quirky to the max and riffing off just about every aspect of Japanese pop culture from Sailor Moon to J-horror, Haruko’s Paranormal Laboratory is a charming, if surreal, take on an early life crisis which must be seen to be believed.

Currently available to stream in the UK from Filmdoo.

Original teaser trailer (dialogue free)

The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion.

The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion.

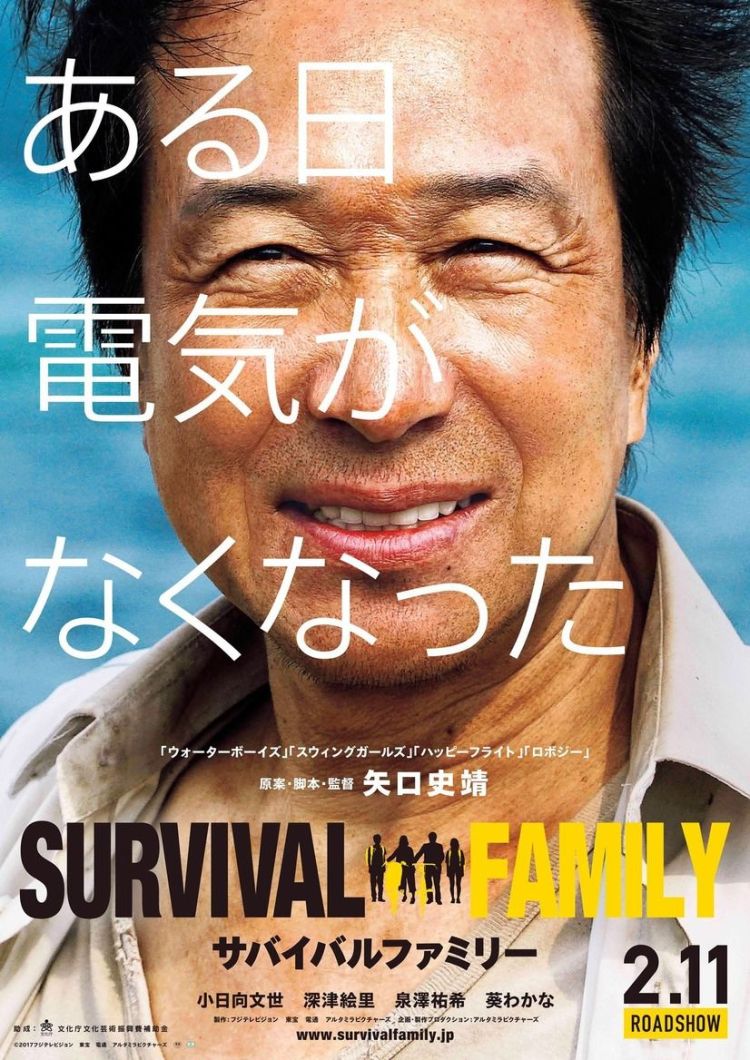

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world. There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s  When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old.

When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old.

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by

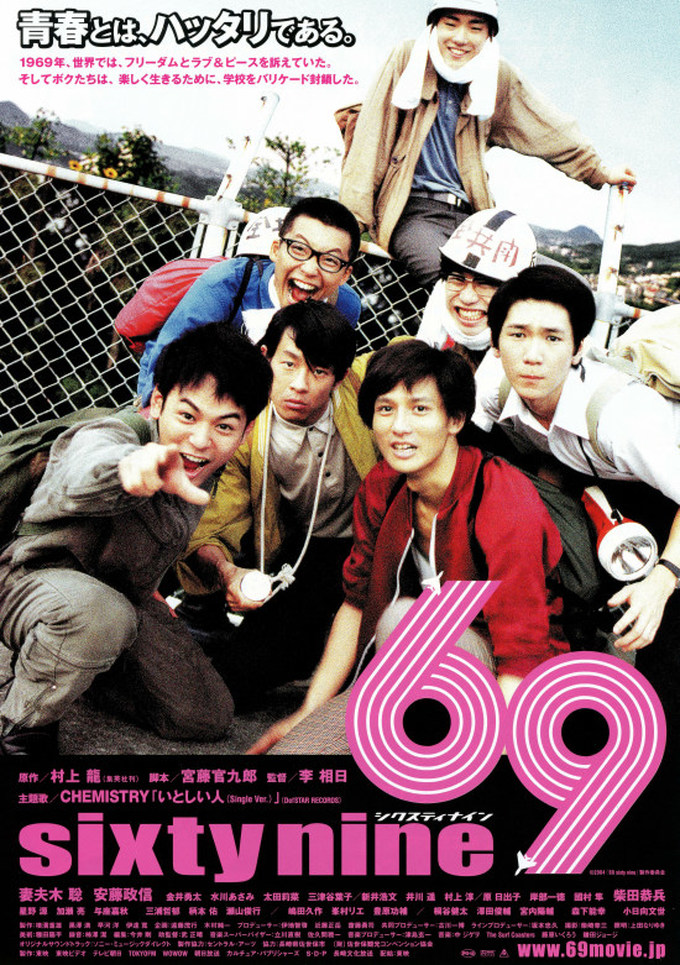

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

Ryu Murakami is often thought of as the foremost proponent of Japanese extreme literature with his bloody psychological thriller/horrifying love story

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.

If there’s one thing you can say about the work of Japan’s great comedy master Koki Mitani, it’s that he knows his cinema. Nowhere is the abundant love of classic cinema tropes more apparent than in 2008’s The Magic Hour (ザ・マジックアワー) which takes the form of an absurdist meta comedy mixing everything from American ‘20s gangster flicks to film noir and screwball comedy to create the ultimate homage to the golden age of the silver screen.