Retitled Samurai Fury (室町無頼, Muromachi Burai) for it’s US release, Yu Irie’s Muromachi Outsiders is indeed a tale of righteous anger though like many jidaigeki the rage is directed towards the corrupt samurai class and wielded by a ronin with a noble heart. Based on a novel by Ryosuke Kakine, it recounts a rebellion that took place five years before the Onin War that would lead to the end the Ashikaga Shogunate and initiate the Sengoku or warring states period that lasted until the Tokugawa era began.

The cause is, really, the incompetent government of shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa (Aoi Nakamura) who is largely seen here gazing out at his view from the palace in Kyoto which he is obsessed with rebuilding. Meanwhile, famine has taken hold following a period of drought that ended with a typhoon and flooding of the river Kamo, and the starvation has also led to a plague. Between the lack of food and disease, 82,000 people will die, but the government doesn’t really do anything because they don’t think the lives of peasants are all that important. This is of course very shortsighted because someone has to plant all that rice that gets delivered to the palace and they can’t do that if they’re too busy starving to death. In the opening sequences, peasants are whipped and beaten as they transport a giant rock for the shogun’s new garden, though when it gets there he doesn’t like it. Meanwhile, a giant pile of bodies in approximately the same shape is dumped at the edge of the river where they’re burning the dead.

The farmers are forced to take such onerous jobs for extra money because they can’t produce enough to pay their taxes which the samurai keep putting up. To make up the shortfall, they have to take out loans from usurious monks who seize their property or take their wives and daughters when they can’t pay. A young man pressed into working for debt collectors from the temple is told to kill a man who owed them money but hits the barrel beside him instead and exposes him for keeping his seed grain without which he won’t be able to plant more rice but they’re going to take that anyway which means that in the end everyone is going to starve. A village favoured by the hero, Hyoe (Yo Oizumi), is also subject raids from disenfranchised ronin who’ve taken to banditry to survive.

Hyoe is also a ronin, but in his life of wandering he’s found a kind of freedom even as he straddles an awkward line, sometimes working with an old friend from the same clan, Doken (Shinichi Tsutsumi), who has turned the other way and is now the security chief for the government in Kyoto with his own gang of bandit dent collectors. Hyoe’s role is, ostensibly, to stop peasant uprisings, which he does, but mostly because he knows they’re pointless and the farmers armed with little more than hoes and stolen armour will simply be massacred, but he’s also secretly plotting a giant rebellion of his own, harnassing the forces of the ronin and the fed up peasants to storm the capital, burn the debt agreements, and rescue the women taken in lieu of payment.

But to do so means he’ll have to betray his oldest friend and that he likely won’t survive. Still he thinks someone’s got to do something about this rotten world and sees a better one beyond it if only they can throw off the yoke of the samurai class that thinks peasants are the same bugs to squeezed dry under their boots. That’s perhaps why he trains a young successor, knowing that can’t remake the world with just this one assault on the mechanisms of government and that even if they get rid of the drunken fool Lord Nawa (Kazuki Kitamura), someone not all that different will pop up in his place. “Tax is supposed to improve people lives,” one of the revolters screams at a young soldier, not pay for a new wing at the palace, though it’s a lesson the young shogun seems incapable of learning even as the city burns all around him.

Taking a leaf out of The Betrayal’s book, the climax is a lengthy action sequence in which Hyoe’s apprentice Saizo (Kento Nagao) takes on half the Kyoto garrison single-handed armed only with his staff. Though the themes are common enough for jidaigeki, though in truth jidaigeki mainly refers to films set in the Edo era under the Tokugawa peace, Irie modernises the way battle is depicted to incorporate wuxia-style wirework and rooftop chases along with martial arts training sequences for the young Saizo who learns the way of the warrior from a cackling old man with a long white beard (Akira Emoto) who has also taken in a young Korean woman (Rina Takeda) who was sold to a brothel by her father in just another one of the injustices of the era but has now become a badass archer and another of Hyoe’s righteous avengers. Solidarity is it seems the best weapon, along with biding your time and knowing when to retreat because this is a war that’s never really won but only held back while the powers that be never really learn.

Samurai Fury is released Digitally in the US Oct. 7 courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)

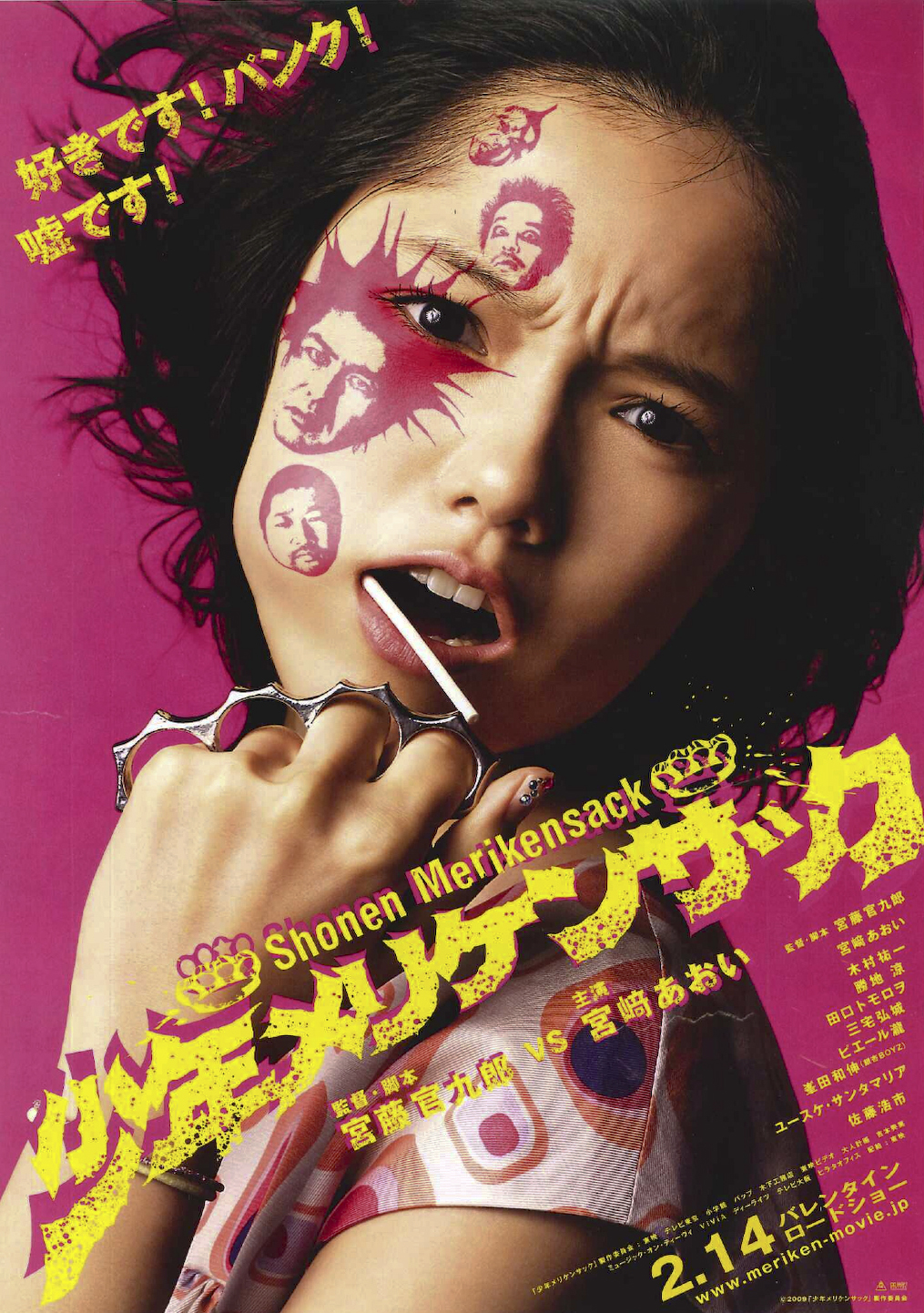

When you spent your youth screaming phrases like “no future” and “fumigate the human race”, how are you supposed to go about being 50-something? A&R girl Kanna is about to find out in Kankuro Kudo’s generation gap comedy The Shonen Merikensack (少年メリケンサック) as she accidentally finds herself needing to sign a gang of ageing never were rockers. A nostalgia trip in more ways than one, Kudo is on a journey to find the true spirit of punk in a still conservative world.

When you spent your youth screaming phrases like “no future” and “fumigate the human race”, how are you supposed to go about being 50-something? A&R girl Kanna is about to find out in Kankuro Kudo’s generation gap comedy The Shonen Merikensack (少年メリケンサック) as she accidentally finds herself needing to sign a gang of ageing never were rockers. A nostalgia trip in more ways than one, Kudo is on a journey to find the true spirit of punk in a still conservative world.