Oshichi returns! Two years after her first adventure, the princess in hiding has moved on, still living in the city hiding from the burdens of privilege but fiercely opposing injustice wherever she finds it as a detective in her own right. Unlike Mysteries of Edo and in keeping with Case of the Golden Hairpins, this Oshichi undergoes much less of a softening, remaining largely disinterested in the idea of romance, and cooly rebellious in her refusal to be cowed while strangely OK with Shogunate oppression as a quasi-agent of the state.

As the film opens, a young woman impersonates Oshichi in order to gain entrance to a prison where her boyfriend is in jail for rebelling against the Shogunate. Meanwhile, Oshichi (Hibari Misora) is teaching a singing class as a favour to her boss who had to go out on an errand, after which she discovers that Hyoma (Chiyonosuke Azuma), currently a retainer of her brother’s, has been sent to bring her home. Once again she refuses because she likes her “ordinary” life. Shortly thereafter, a fire breaks out in the prison and the rebels escape. Oshichi becomes a prime suspect in the jailbreak, not only because the accomplice borrowed her name but because it’s advantageous to the plotters to blame her because they can use her guilt to tarnish her brother’s reputation and get him fired, usurping his position in the process.

Oshichi, now working as a detective, is technically an agent of the Shogunate against which the rebels are rebelling for reasons which aren’t stated here but are probably easy to guess. They are, in many ways, the same sorts of reasons that Oshichi chose to become a detective, even if she’s coming at them from the other side. She doesn’t like bullies, or corruption, injustice or unfairness. Oshichi won’t stand for unkindness either, which is perhaps why she aligns so strongly behind the woman who blackened her name by impersonating her, knowing that she did it all for love and a little bit for justice, while also forgiving the rebel Seinosuke (Kotaro Satomi) who was preparing to kill the woman he loved because the corrupt samurai had kidnapped his dad and threatened to kill him if he didn’t.

Despite all that however, Oshichi still insists that “the Shogunate can be compassionate too”, encouraging Seinosuke and his girlfriend Namiji (Hiromi Hanazono) to tell all so she can help them safe in the knowledge that they will be forgiven. It’s a slightly strange position for to her take, essentially authoritarian but arguing for a benevolent paternalism that is just and fair and kind, insisting that the corrupt samurai are bad apples which must be expelled rather than a product of an inherently oppressive social system as they are generally depicted in post-war jidaigeki.

This insistence on the “compassion” of the Shogunate is perhaps the concession to Oshichi’s femininity which she has otherwise rejected in rejecting her life as a cosseted princess. As Kawashima had in Mysteries of Edo, Oshichi’s “protector” Hyoma asks her how she can take on all those men before challenging her to a contest of masculinity as mediated through a drinking competition which she does not exactly “win” but makes a minor victory all the same. Rather than rely on her brother or Hyoma, Oshichi vows to clear her name herself and starts investigating on her own dressing as a man and fighting bad guys while insisting on her independence.

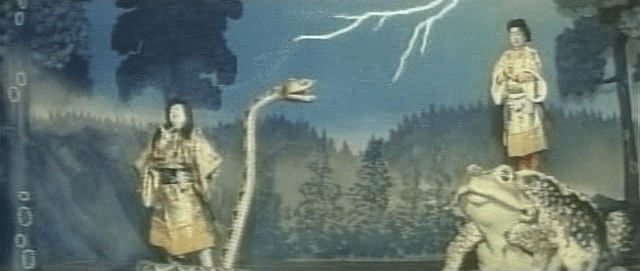

Nevertheless, she is but a pawn in a game of courtly intrigue, manipulated as a means of getting to her brother. The corrupt samurai think nothing of killing anyone who gets in their way, be they princesses or peasants, even going far as to mount an attack on the stage of a theatre mid-performance in front of a room full of spectators, many of whom join Oshichi by throwing projectiles as she tries to fend them off. Once again, she isn’t quite permitted to save herself but is “rescued” by the patriarchal forces representing the greater Shogunate including her protector Hyoma, and her brother, the embodiment of state authority. She is, however, the primary motivator in unmasking the corruption as she both clears her own name, and creates a better future for Namiji in which she can be with the man she loves, reminding her to always remember the compassion the Shogunate has shown her (in case she was minded to mount any more rebellions). As for herself, she manages to slip the loop once again, running off into the wild to claim her independence rather than be forced back into the golden cage of her princesshood while the loyal Hyoma contents himself with following her lead.

Short clip (no subtitles)