An Jung-geun is a key figure in modern Korean history whose story has been dramatised numerous times and given rise to its own legend. JK Youn’s Hero (영웅, Yeong-ung) is, however, the first movie musical devoted to his life and adapted from a stage hit that has been running since 2009. It has to be said that structurally the musical owes a fair amount to Les Misérables with a dramatic first act closer that is more than a little reminiscent of One Day More, while a number about meat buns echoes the kind of comic relief provided by Master of the House, though the rhythm might hint at Sweeney Todd’s meditation on pie making.

It is certainly out of keeping with the intensity surrounding it as the focus is, after all, on an attempt to stop the Japanese colonising Korea and practising even more cruelty. An Jung-geun abandons his family in the early part of the film, but this isn’t seen as a moral failing or irresponsibility so much as evidence of his devotion to the cause that he sacrifices a peaceful life as a husband and father. His revolutionary activity is furthermore filial because his mother encourages it, later writing him a letter while he is imprisoned urging him not to appeal his sentence but accept his death as a martyr. To appeal would mean accepting the Japanese’s authority in begging for his life. Jung-geun had wanted to be tried not as a murderer, but as a soldier fighting a war and therefore sees his trial as illegitimate. He insists he is a political prisoner, a rousing number outlines 15 reasons why the man he assassinated, Ito Hirobumi Japan’s first prime minister and resident-general of Korea, deserved to die which include dethroning the Emperor Gojong, assassinating the Korean Empress Myeongseong (Lee Il-hwa), lying to the world that Korea wanted Japanese protection, plunder, and massacring Koreans (all of which the Japanese had done).

It’s the assassination of Empress Myeongseong that motivates the film’s secondary heroine, Seol-hee (Kim Go-eun), a former palace made now operating as a resistance spy in Japan under the name Yukiko. Seol-hee’s impassioned songs have curiously homoerotic quality and take the place of a central romance which the piece otherwise lacks except in the tentative relationship between Jin-joo, sister of one of An’s closest men, and the youthful recruit Dong-ha. Even if “Myeongseong” is effectively “Korea”, Seol-hee’s passionate intensity is quite surprising while her motivation is more revenge for her murdered mistress than it is saving the nation and eliminating Japanese influence. In this, her arc might not quite make sense in that her final actions almost derail Jeun-guen’s mission in putting the Japanese on high alert.

But at the same time the film leans in far harder on Jeun-geun’s religiosity than other tellings on his story in which his faith presents only a minor conflict as evidenced by his offering an apology to God for killing Ito while justifying his actions as those of a righteous man in the courtroom. While placing him at odds with the left-wing ideology of other Independence activists, his religiosity is aligned with his humanitarian decision to release Japanese prisoners rather than execute them, abiding by the commonly held rules of war while his men are eager for blood. The decision backfires, but is depicted more favourably than in the narratively more complex Harbin and Jung-geun is otherwise an uncomplicated hero who makes no wrong decisions and never fails even if he is at the mercy of the Japanese.

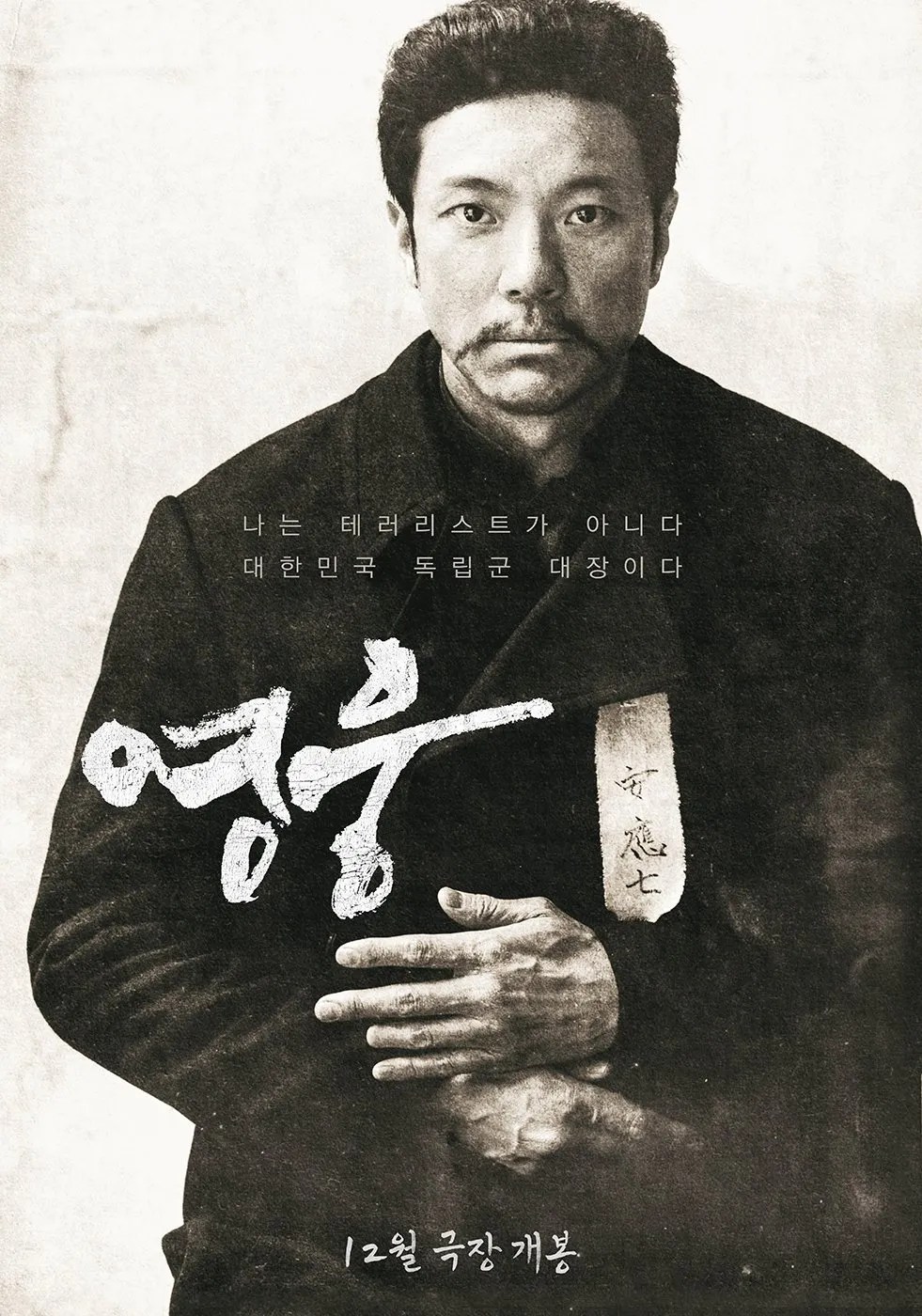

As such, the musical sticks to the familiar beats of Jung-geun’s story from the Japanese counterstrike to his talent for calligraphy and the letter from his mother instructing him to go bravely to his death. Anchored by an incredibly strong vocal performance from Chung Sung-hwa who originated the role on stage, the film portrays Jeun-geung as the hero of the title, defiant to the end and thereafter wronged by the Japanese who buried his body in an unknown location and prevented him from ever returning home to a free Korea. It also glosses over the possibility that Ito’s assassination may actually have accelerated the course of Japan’s annexation which it failed to prevent and otherwise had little lasting effect. Nevertheless, despite its overt patriotism, the film does present the rousing spectacle of Jung-geun’s embodiment of the good son of the nation who fought hard for a liberated Korea he never got to see.

Hero screened as part of this year’s London Korean Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)