Raised in a Buddhist temple after an early orphanhood, documentary filmmaker Yugo Sako became a great devotee of Indian culture and apparently fell in love with the story of the Ramayana while filming a documentary for NHK, later reading as many as 10 different translations of the classic legend in Japanese. Certain that only animation could do justice to this epic tale of gods and demons, he proposed adapting it in the style of Japanese anime which was then gaining in popularity all over the world.

It was though a somewhat sensitive topic. Following a minor misunderstanding concerning Sako’s documentary, complaints were submitted to the Japanese Embassy on behalf of religious organisations who objected to the film on the grounds that it was inappropriate for a Japanese company to adapt their national epic, that their culture was being misappropriated and that they worried the animation format may damage the ethics of the tale. Working with veteran director Ram Mohan, Sako had wanted to make the film in India with Indian animators but given all the difficulties he faced eventually decided to produce it in Japan bringing Mohan and other consultants with him to advise the Japanese animation team how best to reflect the local culture.

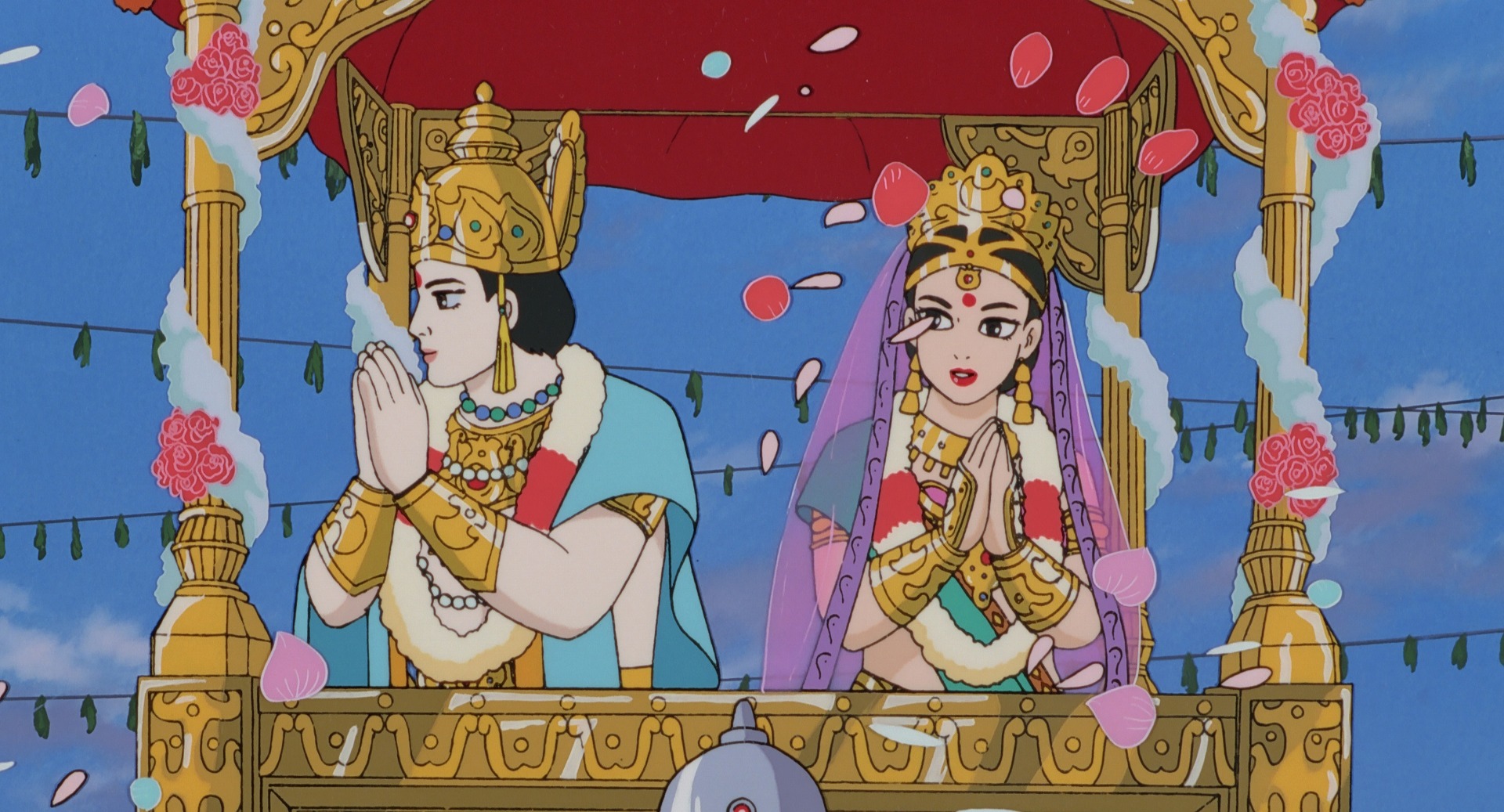

Starring a cast of Indian actors, the film was released first in an English-language audio version only later dubbed into Hindi. In essence it follows Prince Rama (Nikhil Kapoor), the seventh of Lord Vishnu’s 10 incarnations and the first son of a good king, Dasharatha (Bulbul Mukherjee), who rules the happy and prosperous kingdom of Ayodhya. Rama is first called on to deal with a cannibalistic mother and son demon tag team terrorising the local forest but must then tackle the evil demon king Ravana (Uday Mathan) who kidnaps his beautiful wife, Sita (Rael Padmasee), in an attempt to intimidate him during a particularly low point in which he has been exiled to forest for 14 years because of some otherwise fairly gentle palace intrigue. Perhaps surprisingly, each of Rama’s three brothers are also goodhearted and righteous, possessing no desire to unseat him or usurp the throne for themselves despite the machinations of some around them. Rama is also well loved by his people who can see that he is a righteous person prepared to risk his life killing demons to protect them.

Yet the lesson he learns through his journey to defeat Ravan’s darkness once and for all while rescuing Sita, is that it’s more important to be a good person than it is to be a good warrior. He laments that so many have lost their lives in this “avoidable war” and dreams of the day such sacrifices will no longer be necessary while even Sita begins to feel guilty on realising that people from a series of different kingdoms have died to win her freedom. Rama earns the censure of his brother Lakshman (Mishal Varma) when he suggests burning the bodies of fallen soldiers on both sides together, reflecting that they are all the same now and were so even before they died as were the creatures of the mountains and the sea.

Even so, the difference is stark between the gloomy and ominous castle where Ravan holds court and the bright and airy chambers of government in Dasharatha’s home. The animation style is strongly reminiscent of the contemporary work of Studio Ghibli particularly in its depictions of the natural world along with the various demons with whom Rama comes into conflict which may not be surprising given that several key members of the creative team were Ghibli alumni. Yet it also reflects its Indian influences, featuring a soundtrack of traditional music along with several songs performed in sanskrit, musical sequences otherwise not generally a feature of this kind of animation in Japan. Epic in nature, it also employs the voice of a storyteller to fill in the blanks as Rama progresses from one adventure to the next while chasing his quest to free the world from darkness and war as represented by venal Ravan who is not above using trickery to disadvantage his foes nor wilfully sacrificing the lives of his men. Sadly, given the controversy which surrounded it, the film struggled at the box office and was largely relegated to a handful of festival screenings before being rediscovered by its intended audience after India’s Cartoon Network began regularly screening it finally allowing the film to take its place in animation history.

Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama screens at Japan Society New York on Jan. 20 as part of the Monthly Anime series.

Restoration trailer (Japanese narration, English voice track)