Yusaku Matsuda was the action icon of the ‘70s, well known for his counter cultural, rebellious performances as maverick detectives or unlucky criminals. By the early 1980s he was ready to shed his action star image for more challenging character roles as his performances for Yoshimitsu Morita in The Family Game and Sorekara or in Seijun Suzuki’s Kagero-za demonstrate. The Beast Must Die (野獣死すべし, Yaju Shisubeshi, AKA Beast to Die) is among his earliest attempts to break out of the action movie cage and reunites him with director Toru Murakawa with whom he’d previously worked on Resurrection of the Golden Wolf also adapted from a novel by the author of The Beast Must Die, Haruhiko Oyabu. A strange and surreal experience which owes a large amount to the “New Hollywood” movement of the previous decade, The Beast Must Die also represents a possible new direction for its all powerful producer, Haruki Kadokawa, in making space for smaller, art house inspired mainstream films.

Shedding 25 pounds and having four of his molars removed to play the role, Matsuda inhabits the figure of former war zone photo journalist Kazuhiro Date whose experiences have reduced him to state of living death. After getting into a fight with a policeman he seems to know, Date kills him, steals his gun, and heads to a local casino where he goes on a shooting rampage and takes off with the takings. Date, now working as a translator, does not seem to need or even want the money though if he had a particular grudge against the casino or the men who gather there the reasons are far from clear.

Remaining inscrutable, Date spends much of his time alone at home listening to classical music. Attending a concert, he runs into a woman he used to know who seems to have fond feelings for him, but Date is being pulled in another direction as his experiences in war zones have left him with a need for release through physical violence. Eventually meeting up with a similarly disaffected young man, Date plans an odd kind of revenge in robbing a local bank for, again, unclear motives, finally executing the last parts of himself clinging onto the world of order and humanity once and for all.

Throughout the film Date recites a kind of poem, almost a him to his demon of violence in which he speaks of loneliness and of a faith only in his own rage. Later, in one of his increasingly crazed speeches to his only disciple, Date recounts the first time he killed a man – no longer a mere observer in someone else’s war, now a transgressor himself taking a life to save his own. The violence begins to excite him, he claims to have “surpassed god” in his bloodlust, entering an ecstatic state which places him above mere mortals. A bullet, he says, stops time in that it alters a course of events which was fated to continue. A life ends, and with it all of that time which should have elapsed is dissolved in the ultimate act of theft and destruction. His acts of violence are “beautiful demonic moments” available only to those who have rejected the world of law.

Murakawa allows Matsuda to carry the film with a characteristically intense, near silent performance of a man driven mad by continued exposure to human cruelty. Hiding out in Date’s elegant apartment, Matsuda moves oddly, beast-like, his baseness contrasting perfectly with the classical music which momentarily calms his world. Mixing in stock footage of contemporary war zones, Murakawa makes plain the effect of this ongoing violence on Date’s psyche as the sound of helicopters and gunfire resounds within his own head. The imagery becomes increasingly surreal culminating in the moment of consecration for Date’s pupil in which he finally murders his girlfriend while she furiously performs flamenco during an dramatic thunderstorm. Date is, to borrow a phrase, no longer human, any last remnants of human feeling are extinguished in his decision to kill the only possibility of salvation during the bank robbery.

Anchored by Matsuda’s powerful presence, The Beast Must Die is a fascinating, if often incomprehensible, experience filled with surreal imagery and an ever present sense of dread. Its world is one of neo noir, the darkness and modern jazz score adding to a sense of alienation which contrasts with the brightness and elegance of the classical music world. At the end of his transformation, there is only one destination left to Date though his path there is a strange one. Fittingly enough for a tale which began with with darkness we exit through blinding white light.

There’s also another adaptation of this novel from 1959 starring Tatsuya Nakadai which I’d love to see but doesn’t seem to be available on DVD even without subtitles. This film has a selection of English language titles but I’ve used The Beast Must Die as this is the one which appears on Kadokawa’s 4K restoration blu-ray release (sadly Japanese subtitles ony).

Original trailer (no subtitles)

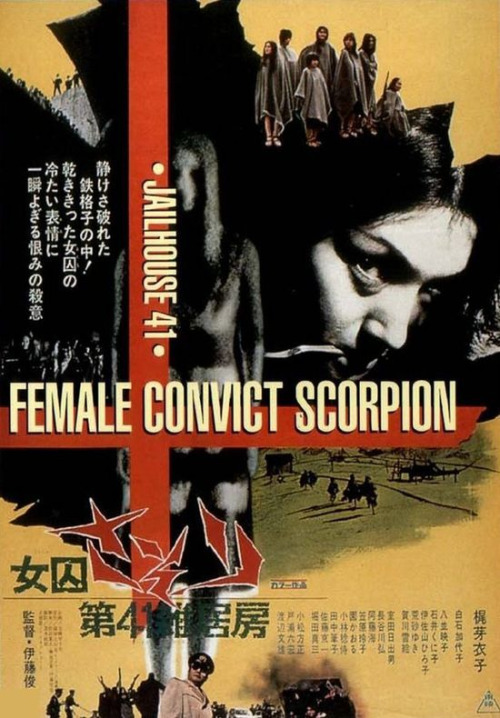

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of  The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as

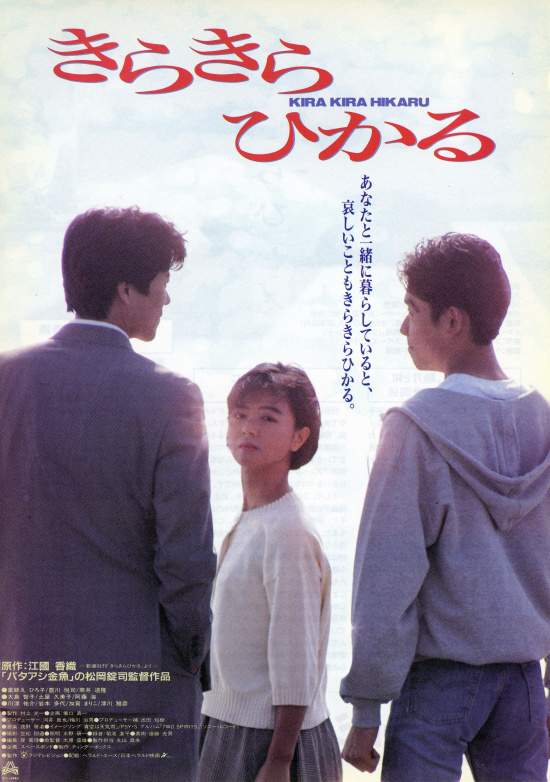

The end of the Bubble Economy created a profound sense of national confusion in Japan, leading to what become known as a “lost generation” left behind in the difficult ‘90s. Yet for all of the cultural trauma it also presented an opportunity and a willingness to investigate hitherto taboo subject matters. In the early ‘90s homosexuality finally began to become mainstream as the “gay boom” saw media embracing homosexual storylines with even ultra independent movies such as  Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted.

Though he might not exactly be a household name outside of Japan, the late Yusaku Matsuda was one of the most important mainstream stars of the ‘70s and ‘80s. Had he not died at the tragically young age of 40 after refusing chemotherapy for bladder cancer to star in what would become his final film, Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, he’d undoubtedly have continued to move on from the action genre in which he’d made his name. No Grave For Us (俺達に墓はない, Oretachi ni Haka wa Nai) is fairly typical of the kinds of films he was making in the late ‘70s as he once again plays a cool, streetwise hoodlum mixed up in a crazy crime world where no one can be trusted.