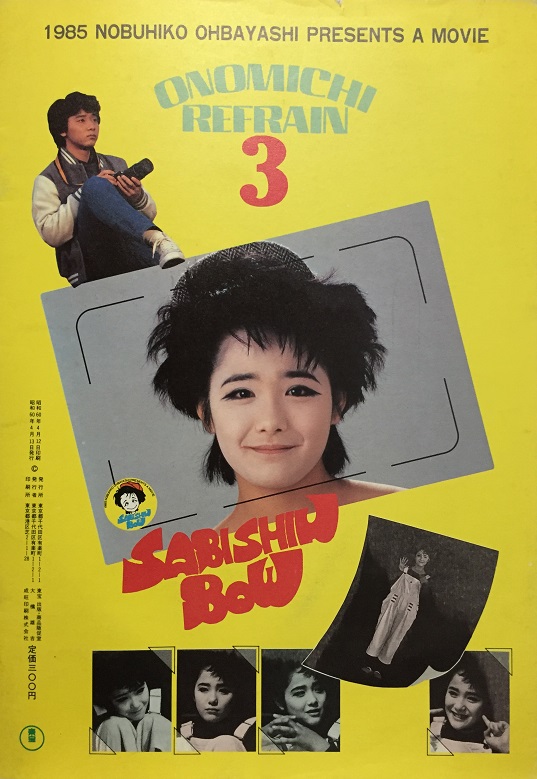

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Obayashi begins with an intertitle-like tribute to a “brusied, brilliant boyhood” before giving way to a wistful voiceover from the film’s protagonist Hiroki Inoue (played by frequent Obayashi collaborator, Toshinori Omi). His life is a fairly ordinary one of high school days spent with his two good friends, getting up to energetic mischief as teenage boys are want to do. The only thing that’s a little different about Hiroki is that his father is a Buddhist priest so he lives in the temple with his feisty mother who is always urging him to study more, and he’ll one day be expected to start training to take over the temple from his father (he has no particular aversion to this idea).

Hiroki’s big hobby is photography and he’s recently splashed out on a zoom lens but rarely has money for film to put in the camera so he’s mostly just playing around, accidentally spying on people. The main object of his interest is a sad looking high school girl who spends her days playing the piano. Hiroki, as an observer of human nature, has decided that she must be just as lonely as he is and has given her the name of “Miss Lonely”. It comes as a shock to him then that a very similar looking sprite appears, also called “Miss Lonely” and proceeds to cause havoc in his very ordinary life.

Although the film is filled with Obayashi’s trademark melancholy nostalgia, there is also ample room for quirky teen comedy as the central trio of boys amuse them selves with practical jokes. The best of these involves a lengthly sequence with the headmaster’s prized parrot which he has painstakingly taught to recite poetry. On being sent to clean up the headmaster’s office after misbehaving in class, the boys quickly set about teaching it a bawdy song instead causing the poor bird to hopelessly mangle both speeches into one very strange recitation. This comes to light when the headmaster attempts to show off his prowess with the parrot to an important visitor but when the mothers of the three boys are called in to account for their sons’ behaviour, they cannot control their laughter. That’s in addition to a repeated motif of the boys’ teacher’s loose skirt always falling off at impromptu moments, and a tendency to head off into surreal set pieces such as the anarchic musical number which erupts at the stall where one of the boys works part time.

Miss Lonely herself appears in a classic mime inspired clown outfit, dressed as if she’d just walked out of an audition for a Fellini film. To begin with, Hiroki can only see Miss Lonely through his camera lens, but she quickly incarnates and eventually even becomes visible to others as well as Hiroki himself. Past and present overlap as Miss Lonely takes on a ghostly quality, perhaps reliving a former romance of memory which may be easily destroyed by water and is sure to be short lived. Love makes you lonely, Hiroki tells us, revelling in the failure to launch of his first love story. Though, if the epilogue he offers us is to be believed, perhaps he is over romanticising his teenage heartbreak and is heading for a happy ending after all.

Chopin also becomes a repeated motif in the film, bringing our trio of lovesick teens together with his music and adding to their romantic malaise with his own history of a difficult yet intense relationship with French novelist George Sand. There’s a necessarily sad quality to Hiroki’s tale, an acceptance of lost love and lost opportunities leaving their scars across otherwise not unhappy lifetimes. Set in Obayashi’s own hometown Miss Lonely takes on a very heartfelt quality, marking a final farewell to youth whilst also acknowledging the traces of sadness left behind when it’s time to say goodbye.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

And here’s idol star Yasuko Tomita singing the title song on a variety show from way back in 1985

Life is full of choices, but the one thing you can’t choose is your family. Like it or not you’re stuck with them for life and even if you decide you want nothing to do with them ever again, they’ll still be hanging round in the back of your mind for evermore. Koreeda swings the camera back around the fulcrum of Japanese society for this dissection of the fault lines and earthquake zones rubbing up against this very ordinary family.

Life is full of choices, but the one thing you can’t choose is your family. Like it or not you’re stuck with them for life and even if you decide you want nothing to do with them ever again, they’ll still be hanging round in the back of your mind for evermore. Koreeda swings the camera back around the fulcrum of Japanese society for this dissection of the fault lines and earthquake zones rubbing up against this very ordinary family. Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation.

Article 39 of Japan’s Penal Code states that a person cannot be held responsible for a crime if they are found to be “insane” though a person who commits a crime during a period of “diminished responsibility” can be held accountable and will receive a reduced sentence. Yoshimitsu Morita’s 1999 courtroom drama/psychological thriller Keiho (39 刑法第三十九条, 39 Keiho Dai Sanjukyu Jo) puts this very aspect of the law on trial. During this period (and still in 2016) Japan does nominally have the death penalty (though rarely practiced) and it is only right in a fair and humane society that those people whom the state deems as incapable of understanding the law should receive its protection and, if necessary, assistance. However, the law itself is also open to abuse and as it’s largely left to the discretion of the psychologists and lawyers, the judgement of sane or insane might be a matter of interpretation. The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go.

The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go. Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,

Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,