Strapping sailors meditate on revenge and forgiveness while trapped aboard a moribund cargo ship in Umetsugu Inoue’s otherwise charming musical youth drama, The Eagle and the Hawk (鷲と鷹, Washi to Taka). One of several films Inoue released starring muse of the moment Ishihara, the film uses the boat as a kind of metaphor for a reluctance to deal with the unfinished past as several of its crew members are actively engaged in a self-imposed limbo wilfully remaining in a transient space floating between two harbours with no plans to disembark.

This is most obviously true for the zombified Ken (Kinshiro Matsumoto) who wanders around the boat in a depressive daze unable to get over a girlfriend who left him for another man though as it turns out the bosun too is hiding out at sea waiting for the statue of limitations to run out on the murder of his lover 30 years previously. When two new recruits show up from the sailors union despite only one having been requested, many are under the assumption that they too are running from something on land though the boat itself is a confined environment from which there is no real escape so it’s also an ideal space for confrontation.

The thing they may be running from is the murder of the boat’s chief engineer in the film’s noirish opening sequence in which a middle-aged man in a sailor’s cap is stalked by a youngster in jeans before being knifed with a ceremonial dagger. If they were running from that particular crime, it might be ironic that they chose this particular boat but then as the murdered man’s son, First Mate Goro (Hiroyuki Nagato), discovers the dagger was part of a set and the other one’s owned by the captain who seems very alarmed by the whole affair. Meanwhile, the captain’s daughter, Akiko (Ruriko Asaoka), has secretly stowed away along with Akemi (Yumeji Tsukioka), the heartbroken former girlfriend of one of the two new guys, Senkichi (Yujiro Ishihara).

Women are regarded as unlucky on board, and it’s not difficult to guess why with Goro offering strict instructions to the new guys not to try anything with Akiko while one of the other sailors later attempts to rape Akemi with a palpable desperation existing within the crew. There is also a degree of homoerotic tension between the two new guys, the other being Sasaki (Rentaro Mikuni) who typically walks around shirtless in a pair of tight jeans and works hard to give the impression of having a mysterious past all of which leads Senkichi to suspect he’s an undercover cop possibly there after him or one of the other crew members though unbeknownst to (almost) everyone there is another crime in motion on board.

As usual, it’s the past that’s come calling with Senkichi on the boat ironically running towards rather than away from a confrontation while others desperately try to cover up their crimes or deflect their responsibility for the dodgy dealings of their youth. Both Senkichi and Sasaki immediately remark that the boat’s a “junker” as soon as they get on board, implying that it too is on its way out, its disrepair a sign of its captain’s lack of respect and care for ship and crew alike. Then again, it seems the crew were intent on drinking half the cargo, most of them clearly happy in their work and enjoying a pleasant sense of camaraderie even on this crummy ship and its presumably not quite above board trip to Hong Kong which might hint at why Akemi shows up in cheongsam though for stowaways both women seem to have brought extensive wardrobes which in all honesty are not particularly well suited to life at sea.

In any case, the boat becomes an unexpected place of healing and forgiveness largely brokered by manly magnanimity as Goro, on learning the truth behind his father’s murder, accepts that the killer’s motivations are “understandable” even while cautioning them against the fallacy of revenge which he insists will only create more hate and violence. He’s also fairly okay with Senkichi romancing his girl, Akiko, who sadly tells him she sees him more like a brother and isn’t interested in marrying him even if that’s what her father also expects neatly reflecting the dynamic which arises between Akemi and the lovelorn Ken who begins to cheer up and consider leaving the boat to open a transistor radio shop only for Akemi to describe him as a little brother while continuing to chase Senkichi despite his interest in Akiko. An expressionistic storm scene provides some divine justice, but also provokes a bittersweet romantic resolution which suggests it’s time to get off the boat and the face the past but with a kind of cheerfulness for the future otherwise at odds with the rage and violence of the original crime. Of course, this being a vehicle for Yujiro Ishihara, Inoue works in a few romantic scenes with his ukulele and a mournful song about the moon and ocean but finally sends him back to dry land a little more “grounded” for having found his sea legs.

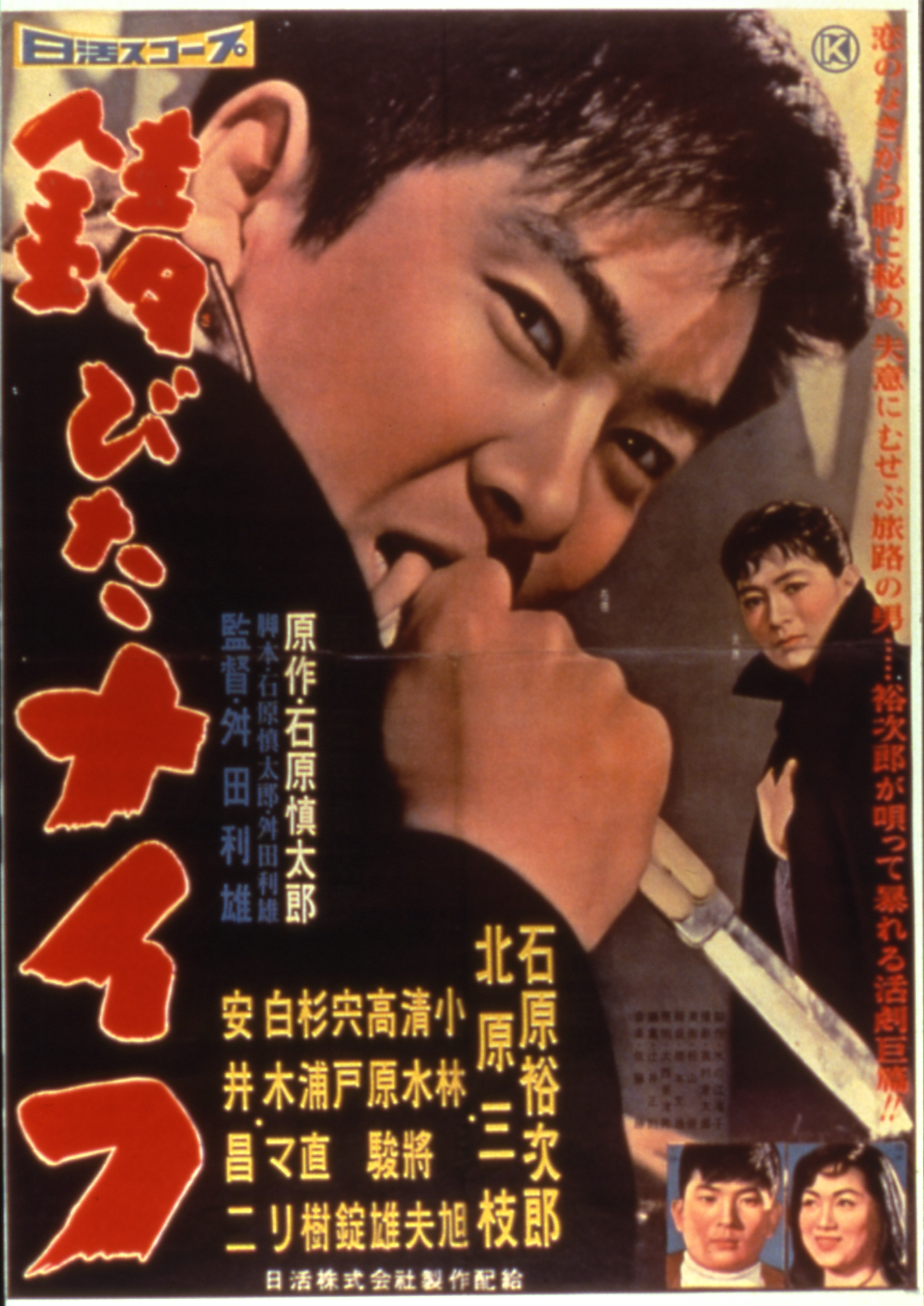

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.