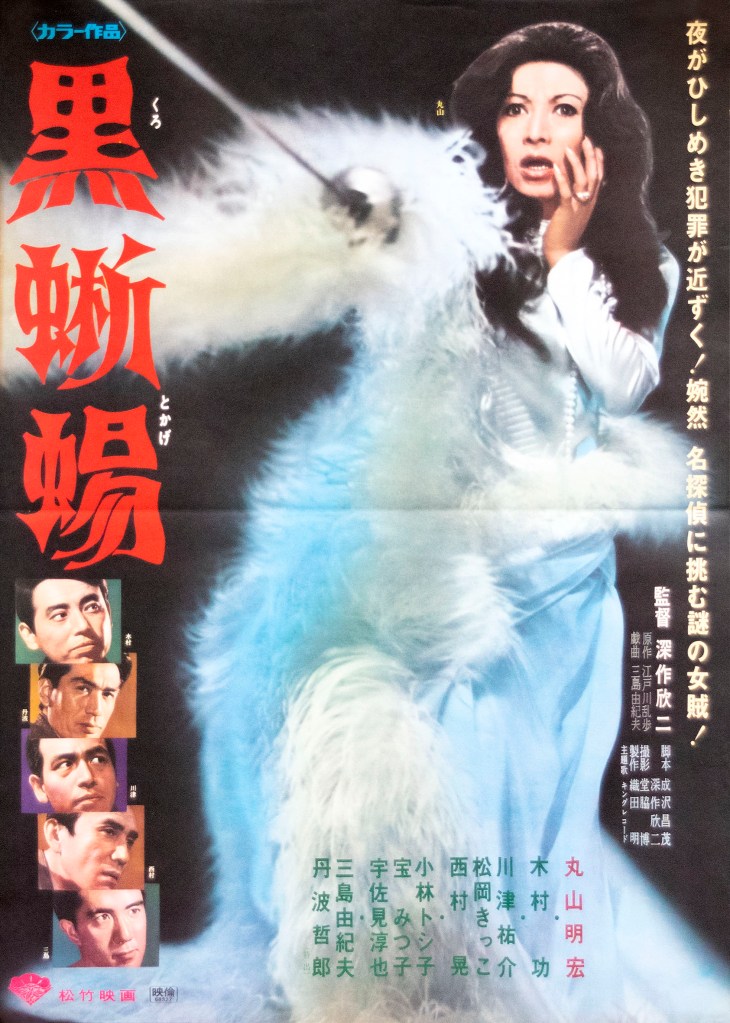

“Are you a critic?” asks the proprietress of of a lively night club, “Why?” replies a lonely man sitting at the bar, “Beauty fails to intoxicate you” she explains before wandering off to find a prettier prize. Nevertheless, a connection has been forged as two masters of the craft confront their opposing number. Black Lizard (黒蜥蝪, Kurotokage), based on the 1934 story by Edogawa Rampo, had been brought to the screen by Umetsugu Inoue in 1962 in a version which flirted with transgression but was frothy and fun, adding a touch of overwrought melodrama and gothic theatricality to Inoue’s well honed musical style.

Inoue’s version had been co-scripted by Kaneto Shindo and Yukio Mishima who had also written the stage version. Once again crediting Mishima’s stage adaptation, Fukasaku’s 1968 take on the story is, as might be expected, far less interested in class connotations than it is in notions of love, beauty, and aestheticism. Consequently, we open in a much harsher world, dropped straight into Black Lizard’s edgy nightclub which Akechi (Isao Kimura), Edogawa Rampo’s famous detective, has visited on a friend’s recommendation. He is shocked to read in the paper the next day that a young man he saw in the club has apparently committed suicide, while another article also mentions the shocking disappearance of a corpse from the local morgue.

Meanwhile, Akechi is brought in on a retainer to protect the daughter of a wealthy jeweller who has been receiving threatening letters informing him of a plot to kidnap her. Unlike Inoue’s version, Iwase (Jun Usami) is a sympathetic father, not particularly demonised for his wealth. Rather than drinking too much, he simply takes his sleeping pills and gets into bed without realising that his daughter is already missing. As transgressive as ever, however, Black Lizard (Akihiro Miwa) wastes no time sizing up Sanae (Kikko Matsuoka), running her eyes over the “splendid curve” of her breasts and lamenting that beautiful people make her sad because they’ll soon grow old. She’d like to preserve that beauty forever, convinced that people age because of “anxieties and spiritual weakness”. The reason she loves jewels is that they have no soul and are entirely transparent, their youth is eternal. Now Black Lizard has her eyes on the most beautiful jewel of all, the Egyptian Star, currently in the possession of Iwase which is why she’s planning to kidnap Sanae and ask for it as a ransom.

Though the Black Lizard of Inoue’s adaptation had been equally as obsessed with youth and beauty, she was a much less threatening presence, never actually harming anyone in the course of her crime only later revealing her grotesque hobby of creating gruesome tableaux of eternal beauty from human taxidermy. This Black Lizard is doing something similar with her “dolls”, but she’s also cruel and sadistic, not particularly caring if people die in the course of her grand plan even running a sword firstly through a body she believes to be Akechi’s, and then through a minion completely by accident. She picks up Amamiya (Yusuke Kawazu) in the bar because of his deathlike aura, his hopelessness made him handsome, but once he fell in deep love with his “saviour” she no longer found him beautiful enough to kill.

Akechi, meanwhile, is captivated by her in the same way Holmes is captivated by Irene Adler. He admires her romanticism, and recognises her as someone who thinks that crime should come dressed in a beautiful ball gown. She, by turns is drawn to him but perhaps as to death, each of them wondering who is the pursuer and who the pursued but determined to be victorious. Casting Akihiro Miwa in the female role of Black Lizard adds an extra layer of poignancy to her eternal loneliness and intense fear of opening her heart, finally undone not by the failure of her crimes but by a sense of embarrassment that Akechi may have heard her true feelings that leaves her unable to go on living.

Meanwhile, Amamiya attempts to rescue Sanae not because he has fallen in love with her, but because he too is drawn towards death. Showing the pair her monstrous gallery of taxidermy figures of beautiful humans, she pauses to kiss one on the lips (played by Yukio Mishima himself no less), leaving Amamiya with feelings of intense jealousy and a longing to be a cold and inanimate shell only to be touched by her. “Sanae”, meanwhile, who turns out to be a perfect mirror in having being picked up at rock bottom by Akechi for use in his plan, guides him back towards life. They did not love each other, yet their “fake” love was set to be immortalised forever as one of Black Lizard’s grim exhibitions. She wonders if the fake can in a sense be the real, that they may free themselves from their respective cages through love in accepting a romantic destiny. For Black Lizard, however, that seems to be impossible. Akechi has “stolen” her heart, but she cannot take hold of his, holding him to be a cold and austere man who has “trampled on the heart of a woman”. “Your heart was a genuine diamond” Akechi adds, lamenting that the true jewel is no more. Black Lizard meets her destiny in a kind of defeat, too afraid of love and the changes it may bring to survive it, but paradoxically grateful that her love is alive while taking her leave as a romanticist in love with the beauty of sadness.

Opening and titles (English subtitles)

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been following the Demon Way for five films, chasing the elusive Lord Retsudo (Minoru Oki) of the villainous Yagyu clan who was responsible for the murder of Ogami’s wife and his subsequent framing for treason. The Demon Way is never easy, and Ogami has committed himself to following it to its conclusion, but recent encounters have broadened a conflict in his heart as innocents and seekers of justice have died alongside guilty men and cowards. Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell (子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ!大五郎, Kozure Okami: Jigoku e Ikuzo! Daigoro) moves him closer to his target but also further deepens his descent into the underworld as he’s forced to confront the wake of his ongoing quest for vengeance.

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) have been following the Demon Way for five films, chasing the elusive Lord Retsudo (Minoru Oki) of the villainous Yagyu clan who was responsible for the murder of Ogami’s wife and his subsequent framing for treason. The Demon Way is never easy, and Ogami has committed himself to following it to its conclusion, but recent encounters have broadened a conflict in his heart as innocents and seekers of justice have died alongside guilty men and cowards. Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell (子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ!大五郎, Kozure Okami: Jigoku e Ikuzo! Daigoro) moves him closer to his target but also further deepens his descent into the underworld as he’s forced to confront the wake of his ongoing quest for vengeance. Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,  When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

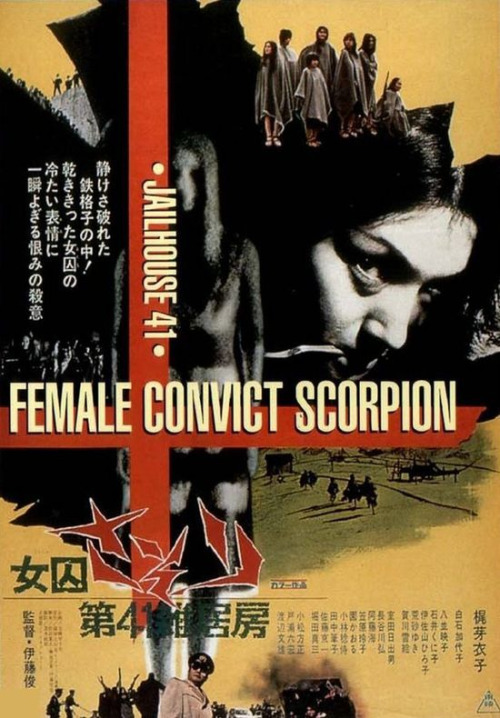

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart. Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of