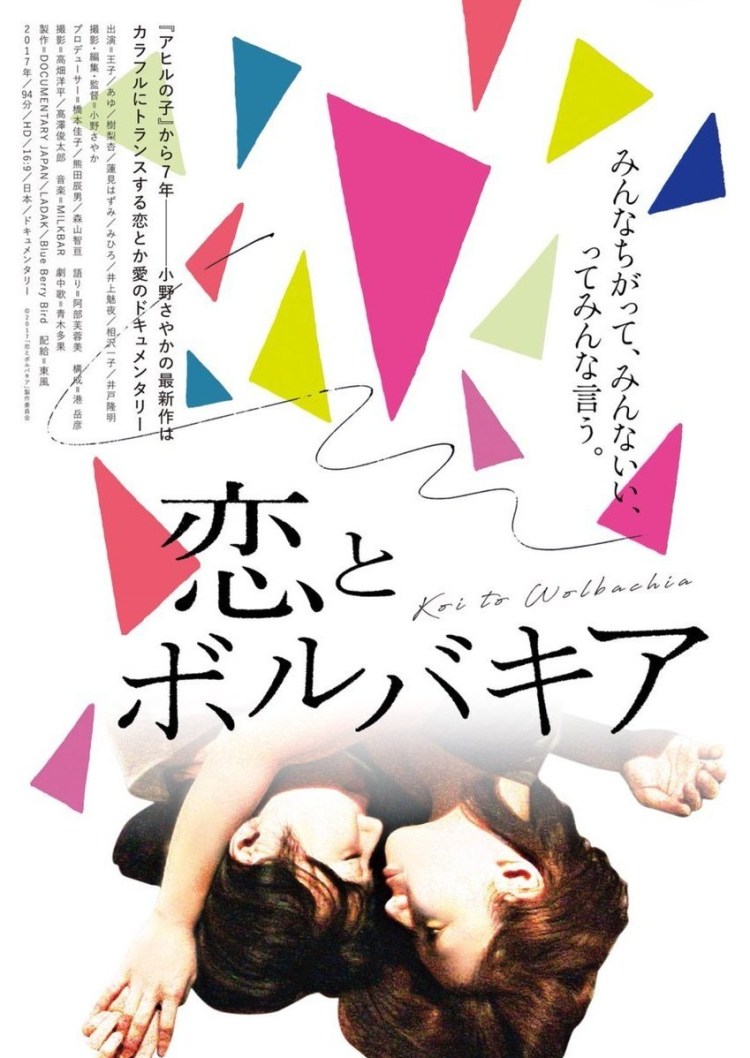

Documentarian Sayaka Ono turned the camera on herself and her family seven years ago with her graduation project/debut feature The Duckling. Returning with her second feature after spending the intervening years in TV documentary, Ono tackles a subject perhaps more distant from her personal experience in exploring the lives of sexual minorities and particularly of transgender women in generally conformist Japan. Love and Wolbachia (恋とボルバキア, Koi to Wolbachia) takes its name from that of a parasitic bacteria which can cause its host to change sex. Love may very well be a kind of virus, but Ono seems more interested in answering the question of why someone might decide to live as a woman in a society so often hostile to them.

Documentarian Sayaka Ono turned the camera on herself and her family seven years ago with her graduation project/debut feature The Duckling. Returning with her second feature after spending the intervening years in TV documentary, Ono tackles a subject perhaps more distant from her personal experience in exploring the lives of sexual minorities and particularly of transgender women in generally conformist Japan. Love and Wolbachia (恋とボルバキア, Koi to Wolbachia) takes its name from that of a parasitic bacteria which can cause its host to change sex. Love may very well be a kind of virus, but Ono seems more interested in answering the question of why someone might decide to live as a woman in a society so often hostile to them.

The first two protagonists Ono introduces us two were born intersex. Despite their personal feelings, each was encouraged to take hormones to conform more closely to their external appearance. Forced to make a perhaps false binary choice, or in essence being deprived of the right to make it for themselves, each has attempted to live in the way which bests suits their authentic selves though they often encounter discrimination and/or hostility from those around them.

The question of gender in and of itself appears more important to some than others. Another of our protagonists, Miya, refers to herself as a “makeup man” and runs a bar which acts as a kind of community space and refuge for other transgender and non-binary people who often have nowhere else to turn. Nevertheless, Miya struggles with her partner’s decision to undergo gender confirmation surgery and finds it difficult to understand why someone would be willing to put themselves through so much pain and suffering for something she sees as an external concern. For Miya the question of “gender” seems moot, not quite something requires only an individual identification but which scarcely requires one at all. It is she feels, in essence, something culturally defined which an individual is free to accept or reject in claiming their own personal identity as distinct from from social codes dictated by society.

Yet Miya also finds herself a victim of these social codes in a desire to provide protection to those who need it only to find herself ill equipped to cope with the intense responsibility of accidentally becoming a community leader if one without a particular political agenda save wanting to make other people’s lives easier. The question of gender roles becomes a more obvious problem in the relationship between lesbian Julian and her transgender partner Hazumi. Criticised by some of her friends for dating a transwoman, Julian also struggles with a perceived expectation to adopt a “masculine” role within the relationship, that Hazumi expects her to provide protection while also becoming the dominant partner which she seems to feel does not fit her personality. Conversely, Julian also longs for a conventional home and family as a married couple with children yet Hazumi wants to transition fully and, having left a marriage and a child to live a more authentic life, worries that starting another family with Julian may prevent her from achieving her dream.

A conventional family life also seems to have prevented 50-year-old Ichiko from pursuing her desire to live as a woman, having lived in a time when few knew such things were possible. A father with three children, most of her resources are given over to their care but she still finds time to enjoy a more authentic life and participate in the community. Like Ichiko, Mihiro began wearing women’s clothing after admiring her wife’s outfits only she later decided to leave her marriage and retains a male personality only for work. Having fallen in love with a man who himself feels uncomfortable with the culturally defined notions of “masculinity”, Mihiro is heartbroken to realise he already has a live-in girlfriend and worries his impression of their relationship may not match her own. This rings eerily true given a solo interview in which he jokingly laments Mihiro’s purehearted approach to romance which he believes leaves her open to male manipulation.

Ono does not particularly explore the lives of transmen, perhaps an anomaly seeing as Japan is one of few nations to have elected a transman to office (Japan also elected its first transgender female politician back in 2003), preferring to explore the place of trans and gay women in a society which can be deeply misogynistic and relentlessly conformist. Mihiro’s supportive mother, watching her carefully applying her makeup, remarks on how much time men must save in not needing to bother. Mihiro partially corrects her – wearing makeup is a choice which is open to women but not perhaps to men and choice, it seems, is the main thing or not so much “choice” but freedom to live in the way you choose rather than the way which is chosen for you by your society.

Screened at Nippon Connection 2018.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.

When you feel you’ve discharged all your social obligations, you might feel as if you’ve a right to live by your own desires. Whether the dreams you abandoned in youth will still be there waiting for you is, however, something of which you can be far less certain. Following the death of her husband, one Filipina grandma decides to find out, taking to the road with her best friend who is, incidentally, wanted for murder and carrying around the severed head of her late spouse in a Louis Vuitton handbag belonging to her vacuous step-daughter, in search of the one that got away.