A collection of frustrated teens find themselves trapped within a literal storm of adolescence in Shinji Somai’s seminal youth drama Typhoon Club (台風クラブ, Taifu Club). “You’ve been acting weird lately” one character says to another, but he’s been “acting weird” too and so has everyone else as they attempt to reconcile themselves with an oncoming world of phoney adulthood, impending mortality, and the advent of desires they either are unable or afraid to understand, or perhaps understand all too well but worry they will not be understood.

Most of the teens seem to look to the pensive Mikami (Yuichi Mikami) as a mentor figure. It’s Mikami they call when some of the girls end up half drowning male classmate Akira (Toshiyuki Matsunaga) after some “fun” in the pool gets out of hand. Luckily, Akira is not too badly affected either physically or emotionally, but presents something of a mirror to Mikami’s introspection. Slightly dim and etherial, he entertains his friends by seeing how many pencils he can stick up his nose at the same time, but he’s also as he later says the first to see the rain once it eventually arrives. Notably he leaves before it traps several of the others inside the school without adult supervision and otherwise misses out on the climactic events inside. Even so, Rie (Yuki Kudo), who also misses out by virtue of randomly stealing off to Tokyo for the day, later remarks that he too seems like he’s grown though her words may also be a kind of self projection.

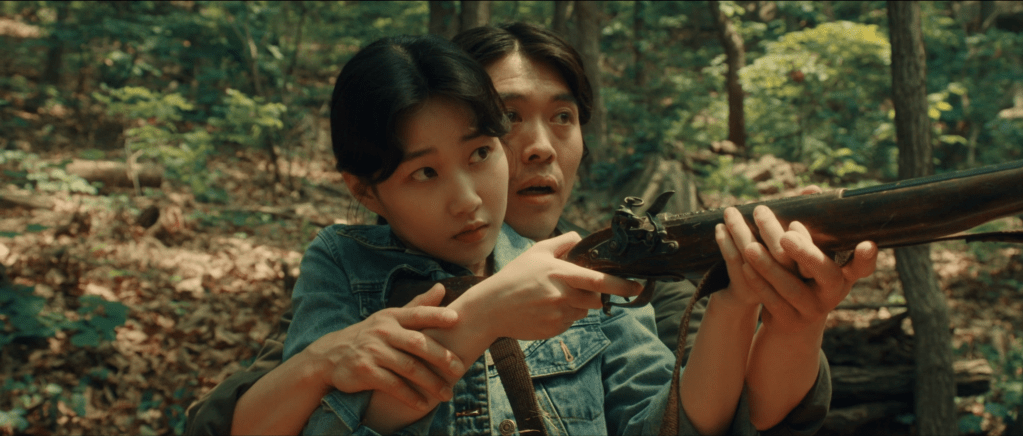

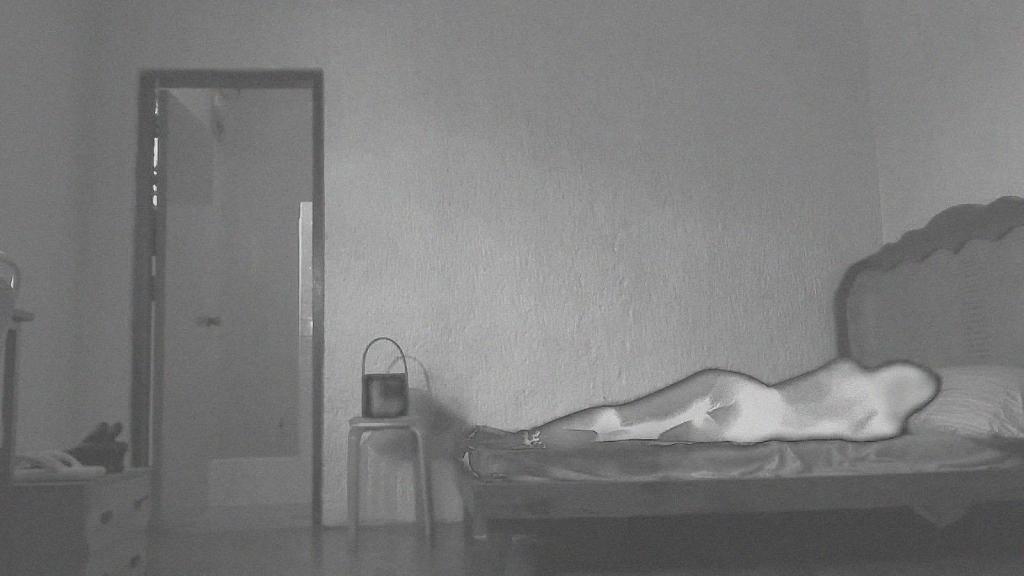

Mikami’s kind of girlfriend, perpetual spoon-bender Rie, finds herself at a literal crossroads after waking up late because her mother evidently did not return home the night before. Eventually she sets off for class running all the way, but then reaches a fork in the road and changes her mind heading to Tokyo instead. Mikami has been accepted into a prestigious high school there, and perhaps a part of her wanted to go too or at least to get closer to him through familiarity with an unfamiliar environment. Unfortunately she soon encounters a firearms enthusiast (Toshinori Omi) who buys her new clothes and takes her back to his flat which she thankfully manages to escape even if she’s stuck in the city because of a landslide caused by the typhoon.

Mikami, however, continues to worry about her unable to understand why he’s the only one seemingly bothered about her whereabouts believing she’s “gone crazy”. Trapped in the school, the kids try to ring their teacher Umemiya (Tomokazu Miura) for help but he’s already drunk and can’t really be bothered. In any case he has problems of his own in that his girlfriend’s mother suddenly turned up during class to berate him for stringing her daughter along and also having borrowed a large amount of money which obviously ought to have some strings attached, only as it turns out Junko leant the money to another guy she was seeing though it’s not exactly clear whether she and Umemiya actually broke up or not. “In 15 years you’ll be exactly like me” Umemiya bitterly intones into the phone when Mikami directly states that he no longer respects him deepening Mikami’s adolescent sense of nihilistic despair.

Of all the teens, he does seem to be the most preoccupied with death. “As long as she’s an egg, the hen can’t fly” he and his brother reflect on discussing if it’s possible for an individual to transcend its species and if it’s possible to transcend it though death all of which lends his eventual decision a note of poignant irony even if its absurd grimness seems to be a strange homage to The Inugami Family. As he points out to his somewhat disturbed friend Ken (Shigeru Benibayashi), “I am not like you” and indeed Ken isn’t quite like the other teens. Obsessed with fellow student Michiko (Yuka Ohnishi) but unable to articulate his feelings, Ken pours acid down her back and watches her squirm as it eats into her flesh. Repeating pleasantries to himself as a mantra, he later attempts to rape her after violently kicking in the dividing walls of the school only to be stopped in his tracks on noticing the scar again and being reminded that he is hurting her.

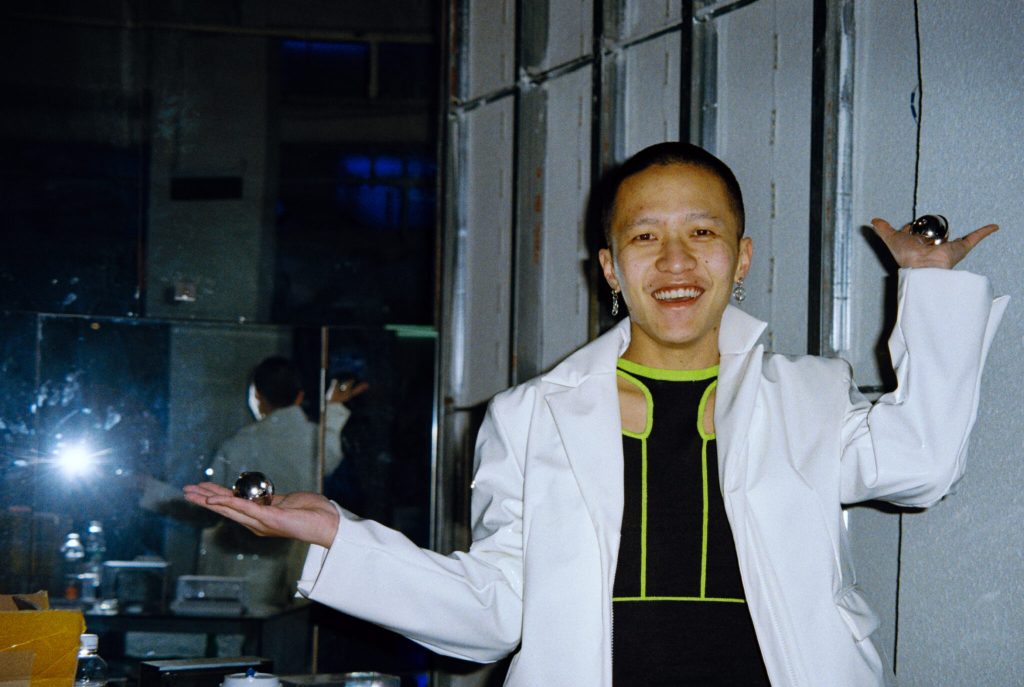

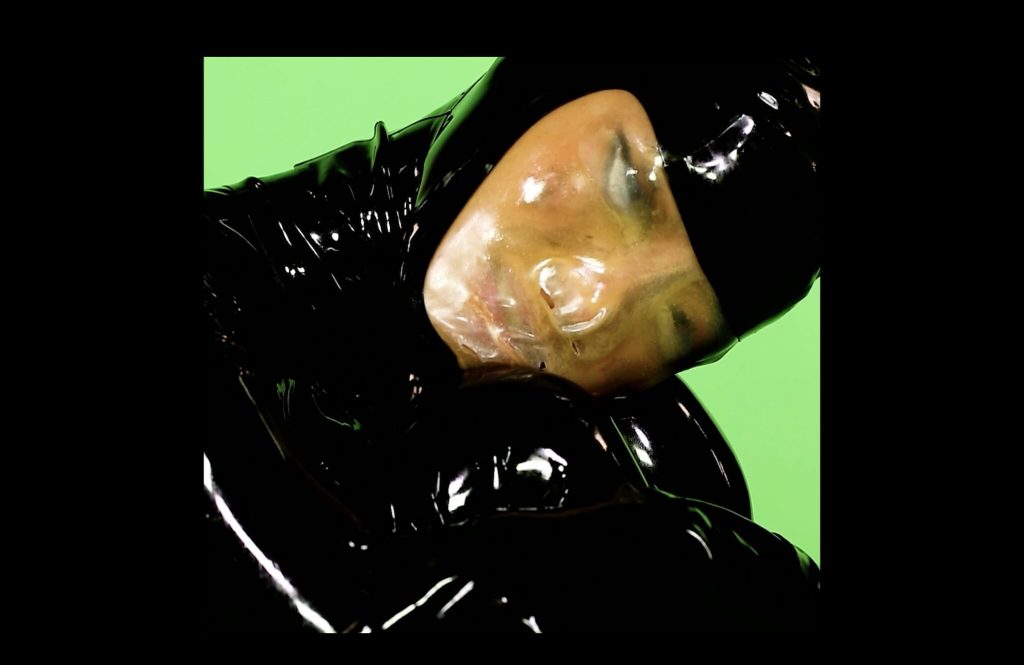

The storm seems to provoke a kind of madness, the teens embracing an elusive freedom entirely at odds with the rigid educational environment. The other three girls trapped in the school are a lesbian couple who’d been hiding out in the drama department and their third wheel friend who might otherwise have been keen to hide their relationship from prying eyes having previously been caught out by a bemused and seemingly all seeing Akira. But in this temporary space of constraint and liberation, the teens are each free for a moment at least to be who they are with even Ken and Michiko seemingly setting aside what had just happened between them. They co-opt the stage for a dance party and then take it outside, throwing off their clothes to dance (almost) naked in the rain while a fully clothed Rie does something similar on the streets of the capital. In some ways, in that moment at least they begin to transcend themselves crossing a line into adulthood in a symbolic rebirth. In any case, Somai’s characteristically long takes add to the etherial atmosphere as do his occasional forays into the strange such as Rie’s encounter with a pair of ocarina-playing performance artists in an empty arcade. “We want to go home, but we can’t move” Mikami says looking for guidance his teacher is unwilling to give him neatly underlining the adolescent condition as the teens begin realise they’ll have to find their own way out of this particular storm.

Typhoon Club screens at Japan Society New York on April 28 as part of Rites of Passage: The Films of Shinji Somai