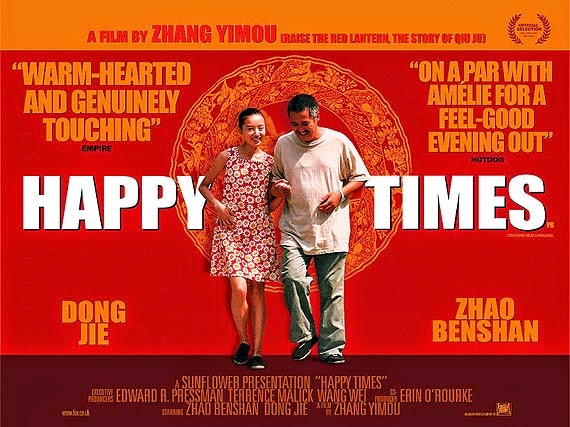

Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways.

Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways.

An older man in his 50s, Zhao is a bachelor afraid that life has already passed him by. Desperate to get married for reasons of companionship, he’s settled on the idea of finding himself a larger lady who, he assumes, will be filled with warmth (both literally and figuratively), have a lovely flat he can move into and will also be able to delight him with delicious food. Not much to ask for really, is it? Unfortunately, he ends up with a woman nicknamed “Chunky Mama” who is pretty much devoid of all of these qualities beyond the physical. She has an overweight son whom she spoils ridiculously and a blind stepdaughter she treats with cruelty and disdain.

Zhao is eager to please his new lady love and has told her a mini fib about being a hotel manager. He and his friend Li had been planning to open a “love hut” in an abandoned trailer in the forest but this plan doesn’t quite work out so when Chunky Mama asks him to give the blind girl, Little Wu, a job in the hotel Zhao is in a fix. Together with some of his friends, he hatches a plan to create a fake massage room in an abandoned warehouse where they can take turns getting massages from the girl in the hope that she really believes she’s working and making money for herself. However, though Little Wu comes to truly love her mini band of would be saviours she also has a yearning to find her long absent father who has promised to get her treatment to restore her sight, as well as a growing sense of guilt as she feels she’s becoming a burden to them.

Zhao decided to name his “love hut” the Happy Times Hotel – to him there’s really no difference between a “hut” and a “hotel”. In some ways he’s quite correct but the expectation differential isn’t something that would really occur to him, straightforward fantasist as he is. In fact, Zhao is a master of the half-truth, constantly in a state of mild self delusion and self directed PR spin as he tries to win himself the brand new life he dreams of through sheer power of imagination. His friends seem to know this about him and find it quite an amusing, endearing quality rather than a serious personality flaw.

Unfortunately this same directness sometimes prevents him from noticing he’s also being played in return. The ghastly stepmother Chunky Mama is in many ways a clear symbol of everything that’s wrong with modern society – brash, forceful, and materially obsessed. For unclear reasons, she’s hung on to Little Wu after the breakdown of the marriage to her father but keeps her in a backroom and forces her do chores while her own son lounges about playing video games and eating ice-cream. Ice-cream itself becomes a symbol of the simple luxuries that are out of reach for people like Little Wu and Zhao but quickly gulped down by Chunky Mama’s son with an unpleasant degree of thoughtless entitlement. The son is a complete incarnation of the Little Emperor syndrome that has accompanied the One Child Policy as his mother indulges his every whim, teaching him to be just as selfish and materially obsessed as she is.

For much of its running time, Happy Times is a fairly typical low comedy with a slightly surreal set up filled with simple but good natured people rallying round to try and help each other through a series of awkward situations but begins to change tone markedly when reaching its final stretch. Zhao and Little Wu begin to develop a paternal relationship particularly as it becomes clear that the father she longs for has abandoned her and will probably never return but circumstances move them away from a happy ending and into an uncertain future. The film ends on a bittersweet note that is both melancholy but also uplifting as both characters send undeliverable messages to each other which are intended to spur them on with hope for the future. “Happy Times Hotel” then takes on its most ironic meaning as happiness becomes a temporary destination proceeded by a long and arduous journey which must then be abandoned as the traveller returns to the road.

Retitled “Happy Times Hotel” for the UK home video release.

US release trailer (complete with dreadful voice over and comic sans):

China is changing. Transforming faster than any other society at any other point in history. This brave new future, flooding in as it has across an ancient nation, has nevertheless left a few islands of dry land untouched by modern progress. Old Liu’s bathhouse is just one of these oases, far away from the big city with its frantic pace and high technology. In the city, you can step into a tiny cubicle and “undergo” a shower inside a contraption that’s just like a carwash, only for people. In Liu’s bathhouse you can relax for as long as you like, laughing and joking with old friends or just hiding out from the world.

China is changing. Transforming faster than any other society at any other point in history. This brave new future, flooding in as it has across an ancient nation, has nevertheless left a few islands of dry land untouched by modern progress. Old Liu’s bathhouse is just one of these oases, far away from the big city with its frantic pace and high technology. In the city, you can step into a tiny cubicle and “undergo” a shower inside a contraption that’s just like a carwash, only for people. In Liu’s bathhouse you can relax for as long as you like, laughing and joking with old friends or just hiding out from the world. It’s a sad truth, but talent isn’t enough to see you succeed in the wider world. In fact, all having talent means is that unscrupulous people will seek to harness themselves to you in the hope of achieving the kind of success which they are incapable of obtaining for themselves. 13 year old Xiaochun is about a learn a series of difficult life lessons in Chen Kaige’s Together (和你在一起, Hé nǐ zài yīqǐ), not least of them what true fatherhood means and whether the pursuit of fame and fortune is worth sacrificing the very passion that brought you success in the first place.

It’s a sad truth, but talent isn’t enough to see you succeed in the wider world. In fact, all having talent means is that unscrupulous people will seek to harness themselves to you in the hope of achieving the kind of success which they are incapable of obtaining for themselves. 13 year old Xiaochun is about a learn a series of difficult life lessons in Chen Kaige’s Together (和你在一起, Hé nǐ zài yīqǐ), not least of them what true fatherhood means and whether the pursuit of fame and fortune is worth sacrificing the very passion that brought you success in the first place. Sometimes God’s comic timing is impeccable. You might hear it said that love transcends death, becomes an eternal force all of its own, but the “love story”, if you can call it that, of the two characters at the centre of Song Hae-sung’s Failan (파이란, Pairan), who, by the way, never actually meet, occurs entirely in the wrong order. It’s one thing to fall in love in a whirlwind only to have that love cruelly snatched away by death what feels like only moments later, but to fall in love with a woman already dead? Fate can be a cruel master.

Sometimes God’s comic timing is impeccable. You might hear it said that love transcends death, becomes an eternal force all of its own, but the “love story”, if you can call it that, of the two characters at the centre of Song Hae-sung’s Failan (파이란, Pairan), who, by the way, never actually meet, occurs entirely in the wrong order. It’s one thing to fall in love in a whirlwind only to have that love cruelly snatched away by death what feels like only moments later, but to fall in love with a woman already dead? Fate can be a cruel master.

Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou).

Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou). Every sovereign needs that one ultra reliable and supremely talented servant who can be called upon in desperate times. For the Dowager Empress of the Qing Empire, that man is Leng Tien-Ying – otherwise known as the Killer Constable. When a sizeable amount of gold goes missing from the Imperial Vaults, it’s Leng they call to try and get it back. However, what Leng doesn’t know is that there’s far more going on here than he could possibly have imagined and he’s about to wade into a trap so deep that you never even see the bottom.

Every sovereign needs that one ultra reliable and supremely talented servant who can be called upon in desperate times. For the Dowager Empress of the Qing Empire, that man is Leng Tien-Ying – otherwise known as the Killer Constable. When a sizeable amount of gold goes missing from the Imperial Vaults, it’s Leng they call to try and get it back. However, what Leng doesn’t know is that there’s far more going on here than he could possibly have imagined and he’s about to wade into a trap so deep that you never even see the bottom.

Generally speaking, capitalists get short shrift in Western cinema. Other than in that slight anomaly that was the ‘80s when “greed was good” and it became semi-acceptable to do despicable things so long as you made despicable amounts of money, movies side with the dispossessed and downtrodden. Like the mill owners of nineteenth century novels, fat cat factory owners are stereotypically evil to the point where they might as well be ripping their employees heads off and sucking their blood out like lobster meat. Zhang Wei’s Factory Boss (打工老板, Dagong Laoban) however, attempts to redeem this much maligned figure by pointing out that it’s pretty tough at the top too.

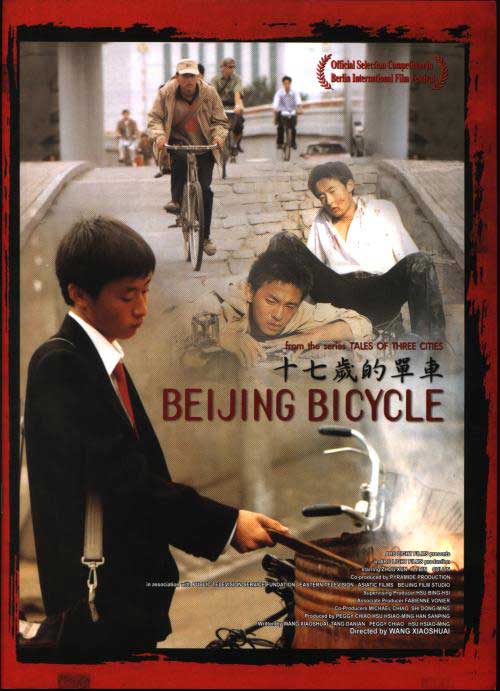

Generally speaking, capitalists get short shrift in Western cinema. Other than in that slight anomaly that was the ‘80s when “greed was good” and it became semi-acceptable to do despicable things so long as you made despicable amounts of money, movies side with the dispossessed and downtrodden. Like the mill owners of nineteenth century novels, fat cat factory owners are stereotypically evil to the point where they might as well be ripping their employees heads off and sucking their blood out like lobster meat. Zhang Wei’s Factory Boss (打工老板, Dagong Laoban) however, attempts to redeem this much maligned figure by pointing out that it’s pretty tough at the top too. There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.

There are nine million bicycles in Beijing (going by the obviously very accurate source of a chart topping song) but there are 11.5 million inhabitants so that’s at least two million people who do not own a bike. Still, if you’re in the unlucky position of having your bike stolen by one of the aforementioned two million, your chances of finding it again are slim. Luckily for the protagonist of Wang Xiaoshuai’s Beijing Bicycle (十七岁的单车, Shí Qī Suì de Dānchē), he manages to track his down through sheer perseverance though even once he gets hold of it again his troubles are far from over.