Home video may still have been in a nascent and chaotic stage of development when Toei video executive Tatsu Yoshida began conducting customer research in video rental stores, but what he discovered shocked him. Customers were maxing out their five video allowance and watching them all the same evening. How did they have time for that, he wondered. The answer was that they were watching them all on fast forward to cut out the boring bits, like the story and exposition. It was this that gave him the idea to create “movies that will not be fast forwarded,” chiefly because they had already been excised of anything “inessential”.

Only an hour in length, 1989’s Crime Hunter: Bullets of Rage (クライムハンター 怒りの銃弾, Crime Hunter: Ikari no Judan) was the first in Toei’s new V-Cinema range and was indeed made to conform to these aims. Consequently, it focuses mainly on action with minimal narrative and relies on genre archetypes to help the plot move along. In that, it owes something to Nikkatsu’s borderless action films in taking place in Little Tokyo (largely filmed in Okinawa) though otherwise in a world that’s recognisably Japanese despite the English-language police radio and Japanese-American names like that of fugitive criminal Bruce Sawamura (Seiji Matano) and Joe “Joker” Kawamura (Masanori Sera), the cop who’s trying to track him down but only as a means to an end in his quest to avenge the death of his partner, Ahiru (Riki Takeuchi). We can tell that Ahiru’s not going to last long in this film because we’re told quite quickly that he’s been invited to the chief’s daughter’s birthday party and is seen as a potential suitor, while after apprehending Bruce he complains that his mother bought him the shirt that’s now been stained.

Joker’s attachment to Ahiru goes a little beyond that of a mere partner as he hands back his badge to pursue revenge while picking up the empty packet of pop-corn Ahiru had been eating and placing it over his heart. The film seems to owe a lot to contemporary Hong Kong action films and Heroic Bloodshed such as A Better Tomorrow, and it’s apparent that this almost homoerotic relationship between the men has taken the place of heteronormative romance. The female star, Lily (Minako Tanaka), is (nominally at least) at nun which makes her romantically unavailable to Joker or indeed to Bruce while in some senses she represents opposition because her cause is at odds with Joker’s. While they temporarily align in wanting to find Bruce, Joker wants information that will lead him to the identity of his partner’s killer, while for Lily he’s the endgame because she wants to get back the money he stole from the donation box at her church.

This whole narrative strand doesn’t make a lot of sense in that Lily says she accidentally told Bruce about the donations after having too much to drink at a party with her non-nun girlfriends, which is strange behaviour for a bride of Christ. Now she feels like retrieving the money is her responsibility, though Joker isn’t really interested in that. What he discovers is further kinship with the fugitive Bruce on realising that they’ve both become victims of a corrupt police force. The opening police radio broadcast implies that Little Tokyo has become an oppressive police state in which the threat of drugs and gangs is being used to control people while cops like Joker have been given blanket permission to aim at the head of suspected criminals as they do while arresting Bruce. Joker had thought that the guys who attacked them were Bruce’s men breaking him out or otherwise trying to steal the money off him, only to later realise they were actually corrupt police.

But really not much of that matters in comparison to the increasing outlandishness as Lily transitions from wimple-wearing bad ass sister to a nightclub dancer femme fatale in fishnets infiltrating the Cathay Tiger gang with expertly crafted dance routines. Former mercenary Bruce similarly boasts and improbably impressive arsenal of grenade launchers and machine guns before arriving at the depressing environment of a disused industrial complex for the nihilistic showdown in which Joker realises there is no way to right this world of corruption and that he and Bruce weren’t so different in each being controlled and defined by an oppressive society in which there are no happy endings even for heroes.

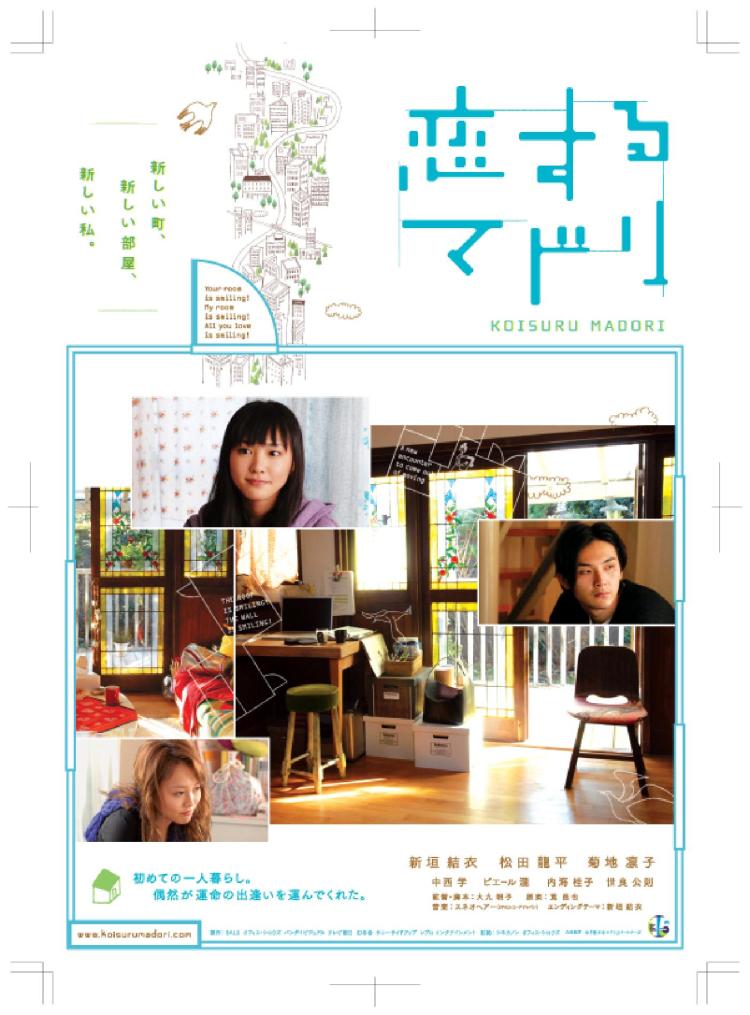

Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint.

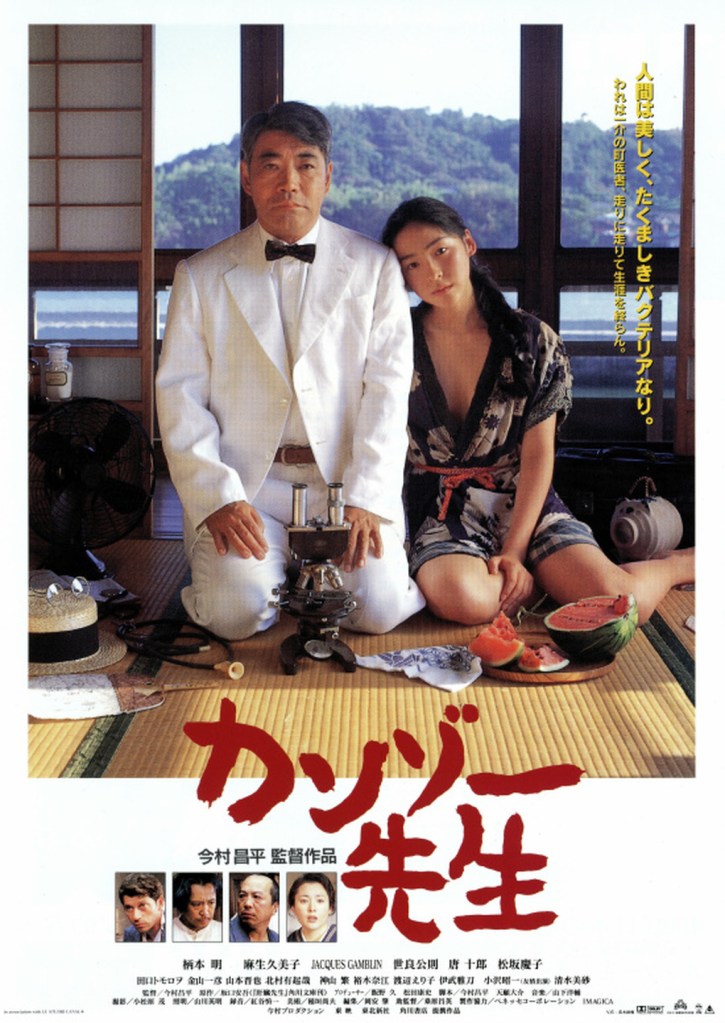

Cities are often serendipitous places, prone to improbable coincidences no matter how large or densely populated they may be. Tokyo Serendipity (恋するマドリ, Koisuru Madori) takes this quality of its stereotypically “quirky” city to the limit as a young art student finds herself caught up in other people’s unfulfilled romance only to fall straight into the same trap herself. Its tale may be an unlikely one, but director Akiko Ohku neatly subverts genre norms whilst resolutely sticking to a mid-2000s indie movie blueprint. A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.