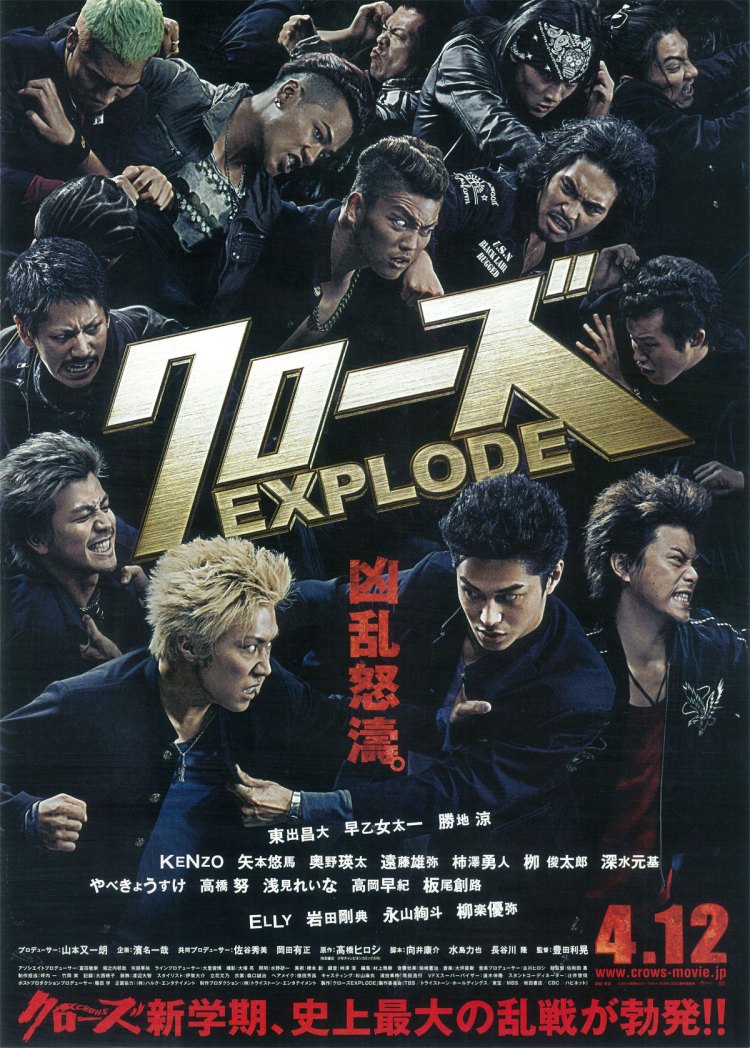

Toshiaki Toyoda made an auteurst name for himself at the tail end of the ‘90s with a series of artfully composed youth dramas centring on male alienation and cultural displacement. Attempting to move beyond the world of adolescent rage by embracing Japan’s most representative genre, the family drama, in the literary adaptation Hanging Garden, Toyoda’s career hit a snag. Despite the film’s favourable reception with critics, a public drugs scandal cost Toyoda his career in Japan’s extremely strict entertainment industry. Since his return to filmmaking in 2009 Toyoda has continued to branch out but 2014’s Crows Explode (クローズ EXPLODE) throws him back into that early world of repressed male energy as internalised rage and frustration produce externalised violence. Picking up the Crows franchise where Takashi Miike left off, Toyoda brings his unique visual sensiblilty to the material, swapping Miike’s irony for something with more grit but losing the deadpan depth of its adolescent posturing in the process.

Toshiaki Toyoda made an auteurst name for himself at the tail end of the ‘90s with a series of artfully composed youth dramas centring on male alienation and cultural displacement. Attempting to move beyond the world of adolescent rage by embracing Japan’s most representative genre, the family drama, in the literary adaptation Hanging Garden, Toyoda’s career hit a snag. Despite the film’s favourable reception with critics, a public drugs scandal cost Toyoda his career in Japan’s extremely strict entertainment industry. Since his return to filmmaking in 2009 Toyoda has continued to branch out but 2014’s Crows Explode (クローズ EXPLODE) throws him back into that early world of repressed male energy as internalised rage and frustration produce externalised violence. Picking up the Crows franchise where Takashi Miike left off, Toyoda brings his unique visual sensiblilty to the material, swapping Miike’s irony for something with more grit but losing the deadpan depth of its adolescent posturing in the process.

The old gods have fallen and new ones must rise. Tough guys graduate, but the battlefields of Suzuran High endure eternally. Suzuran is the ultimate in delinquent schools. None of the boys here are under any misapprehension that the adult world holds any promise for them. Many will drop out without completing high school, condemning themselves to a precarious life of continually uncertain, low paid employment, but even those who do manage to leave with a certificate will be heading into another competition to find a steady job in economically straightened times.

That is, those of them who don’t end up in a gang. The thing at Suzuran is that your fate is determined by your fists. Boys roam the halls looking for a fight, each vowing to become the top dog and de facto leader by proving themselves the best and the strongest of the strapping young men all vying for the title. A new challenger arrives in the form of transfer student, Kaburagi (Masahiro Higashide), whose intense energy upsets the dynamic between presumed number one Goura (Yuya Yagira) and his challenger Takagi (Kenzo) but Kagami (Taichi Saotome), the loner son of a fallen yakuza, seems further set to pose a threat in this knife edge environment.

Toyoda has some interesting points to make about the legacy of violence and the importance of father son relationships as each of these young men is reacting in some sense against a father or just his father’s world. Kaburagi, the film’s protagonist, is nursing a deep wound of double abandonment after witnessing his father’s death and then being deposited in a foster home by his sorrowful mother who promises to return for him soon but makes do with occasional visits and monetary gifts. Kaburagi is an angry young man and like many angry young men, he is eager not to become his father – a situation complicated by the fact that his father was a prize fighter who died in the ring.

His “mirror” Kagami, has a similar problem only his father died in a yakuza turf war. A surrogate presents himself in the form of former Suzuran scrapper “Jarhead Ken” (Kyosuke Yabe), now an ex-yakuza helping out at a friend’s second hand car dealership but unable to escape gangland troubles when it emerges Kagami’s clan are intent on acquiring it in order to turn the place into some kind of “entertainment complex”. Ken, a tough guy but soft hearted, has a talent for paternalism which he turns on the fatherless little boy of the car dealership’s owner to whom he teaches the importance of a hefty punch but also of friendship and loyalty.

Miike’s world was a surreal one, inflected with a wry middle aged eye which sees all of this teenage rambunctiousness for the ridiculous posturing it really is. Toyoda’s attempts to be more in the moment, experiencing the adolescent angst with all of its immediate force but unlike his early protagonists the boys of Suzuran are forced to “explode” rendering that central tenet of repressed anger redundant. Externalising the internal war somehow makes it much less interesting as boys trade blows, mindlessly trying to work out a mental struggle which their ill drawn backgrounds will not support.

The environment which the boys inhabit is a grey and hopeless one. Toyoda paints it with his characteristic visual flair, returning to his trademark sequences of slow motion coupled with indie music, but his energy is very different from Miike’s and its more contemplative rhythm never quite gels with the pugilistic fury of the source material even as it gives way to his more expressionistic imagery. The franchise is feeling a little punch drunk by this point, and Toyoda finds it in a particular puddle of teenage malaise. Still, the fists fly and the boys of Suzuran rise and fall as always providing enough self consciously cool action to sustain interest despite the otherwise insubstantial quality.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like

Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like