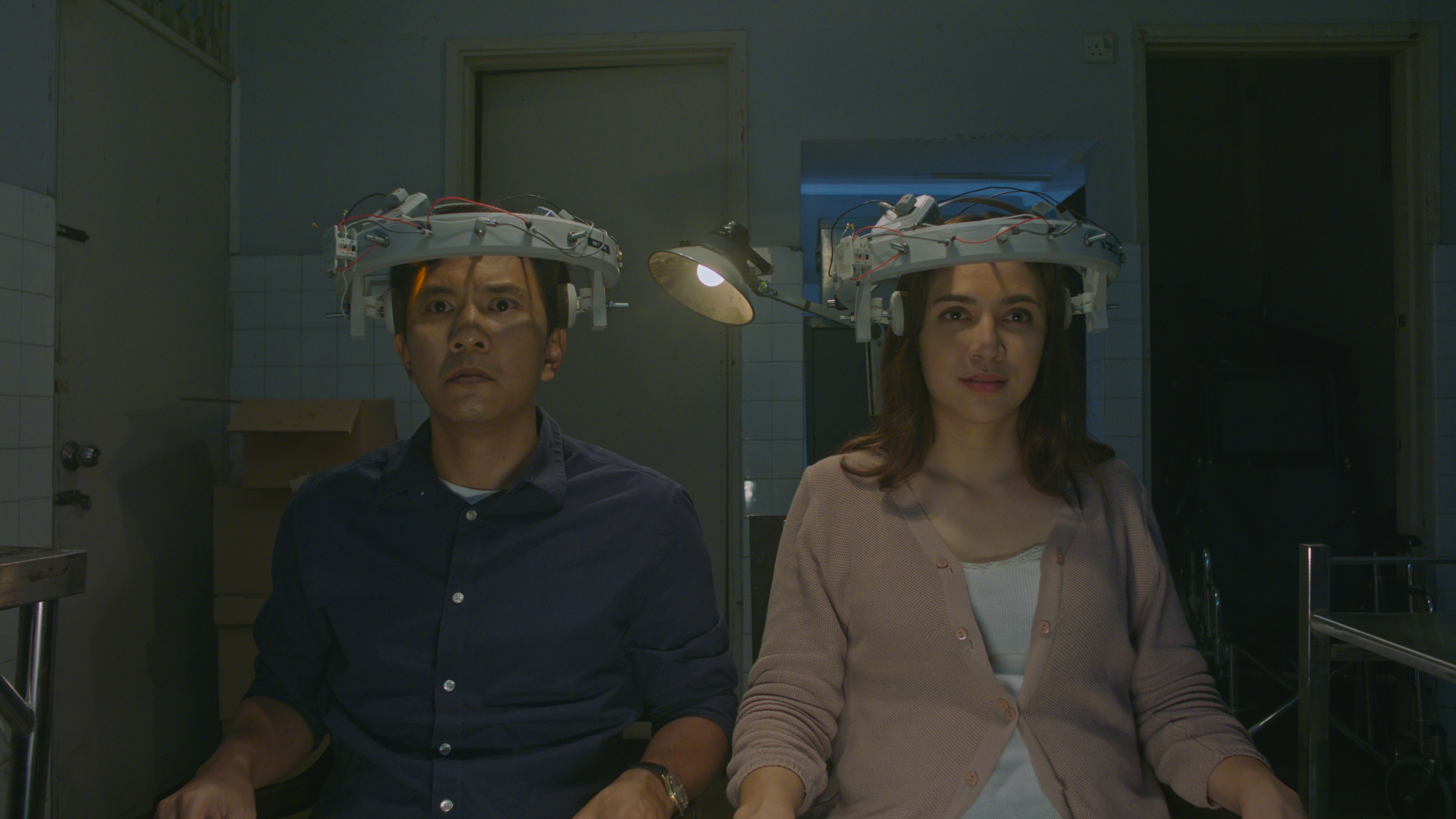

Parental disconnection and the legacy of abuse come under the microscope in a dark psychological thriller from Kazuya Shiraishi, Lesson in Murder (死刑にいたる病, Shikei ni Itaru Yamai). Adapted from the novel by Riu Kushiki, the film’s ironic Japanese title means something more like Sickness Unto Death Sentence and hints at an almost spiritual infection that spreads violence and cruelty as embodied by the moral vacuum at the film’s centre, a genial serial killer of stereotypically “good” kids chillingly played comic actor Sadao Abe.

The psychodrama is played out, however, in the mind of young legal student Masaya (Kenshi Okada) who once frequented the popular bakery owned by Yamato (Sadao Abe) before he was exposed as the killer of 23 teens and one adult woman. On returning home for his grandmother’s funeral, Masaya is surprised to receive a letter from Yamato asking for his help. He admits killing the 23 teens (and perhaps more) but claims that he is not responsible for the death of the adult woman who after all does not fit his pattern. As he reveals, Yamato killed teens in their last year of high school and the grooming process which may have started even years before was central to his M.O. He delighted in winning their trust and then betraying it by torturing them to death in a smokehouse on the grounds of his isolated farmhouse.

In court, Yamato explains that killing is simply “essential” to his being while insisting that he was caught because he became complacent rather than as a result of efficient policing. Yet he tells Masaya that it annoyed him that he never fell under suspicion, people always trusted him without question and he wanted to challenge that level of social complacency. In any case what’s clear is that he is and has always been a manipulative narcissist attributing those personality traits to his childhood abuse implying that they were a part of an abandoned child’s defence mechanism. He praised others to make them love and protect him, becoming drunk on the power he held over them. At first it seems as if his killings stem from resentment towards these “perfect” children who were well behaved and studied well in school but in fact the reason the children behaved in that way was often born of a desire for parental approval which made them vulnerable to Yamato’s grooming. “Repressed children have low self-esteem” he tells Masaya, an abused child himself, claiming that he wanted to help them grow in confidence through his persistent love bombing.

Masaya is also on some level being groomed and may at times even be aware of it, but is so consumed with resentment towards his own father that he longs for a more sympathetic father figure and is even willing to accept to a serial killer as a potential paternal mentor. He becomes desperate to prove Yamato didn’t kill Kaoru (Ryo Sato), a 26-year-old office worker, almost forgetting that the killing of the 23 teens is not in dispute. His father resents him because the family run a prestigious school but Masaya was not academically gifted, bullying and beating both Masaya and his mother who is also an underconfident survivor of childhood neglect. She constantly asks for Masaya’s help making decisions, as do other survivors that he meets, while Yamato ironically tells him that the choice to investigate Kaoru’s death is entirely his own while wilfully manipulating him. Even so under his influence, Masaya’s own feelings of resentment towards the conservative society as mediated through middle-aged salarymen eventually bubble to the surface leading him on a dark path towards a potentially murderous destiny.

Then again, as much as Yamato tries to take control of the narrative Kaoru’s death would still have been as a result of his actions no matter who it was who actually killed her. In another uncomfortabe irony what he’s doing while clearly grooming Masaya is in a sense as he claimed to be doing with his victims restoring his self-confidence in forcing him to face his dysfunctional family situation while proving that he is capable of solving this crime and perhaps in the end solving it a little better than intended. A killer final twist lends an additional layer of insanity to Yamato’s banal evil while Shiraishi’s cool direction at times superimposing the faces of the two men one over another in the glass that divides them at the prison with the faces of the victims projected behind may suggest that darkness hangs all around us and more to the point within.

Lesson in Murder screens at Lincoln Center 21st July as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Images: ©2022 ”Lesson in Murder” Film Partners