A pair of exiles from mainstream society develop a bond that allows for mutual evolution, but are their feelings genuine or the result of a love bug and does it really matter anyway? Kensaku Kakimoto’s adaptation of the light novel by Sugaru Miaki Parasite in Love (恋する寄生虫, Koi suru kiseichu) finds a germophobic man planning to plant a virus to destroy the world he thinks has rejected him coming to care for a young woman who cannot face the glare of a judgemental society while asking if love were a sickness would you really want to be “cured” and if its sacrifice would be worth the price of living a “normal” life.

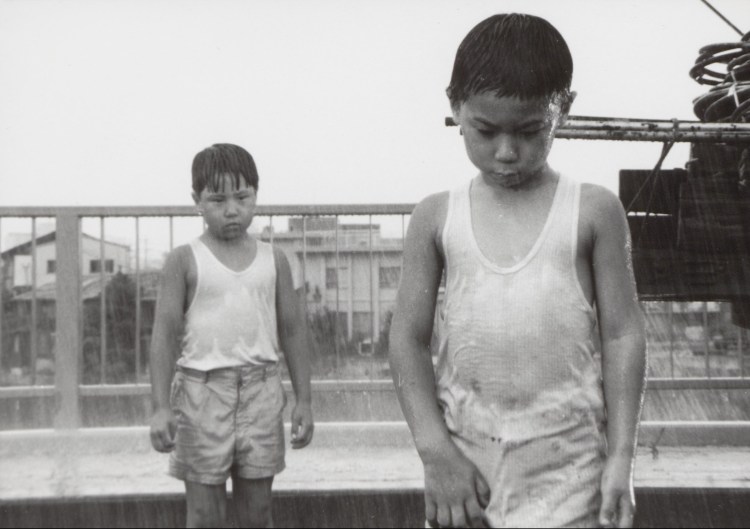

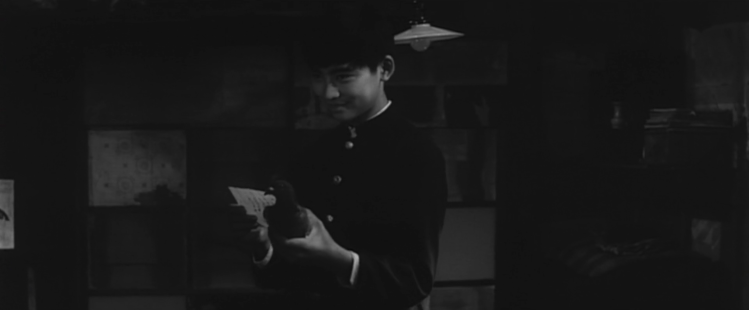

Kosaka (Kento Hayashi) lost his parents to suicide at eight years old and has been alone ever since. He is terrified of the world around him believing that everything and everyone is covered in dangerous pathogens and leaves his apartment, where he is busy writing a virus designed to disrupt communication between devices in an ironic revenge for his own inability to connect, only when necessary. On one such trip, however, he runs into high schooler Hijiri (Nana Komatsu) who cannot bear to see other people’s eyes and wears headphones to block out the interpersonal noise of the mainstream society. Where Kosaka chooses isolation because he fears infection, Hijiri is convinced she has a life-limiting parasite in her brain which is infectious to others and does not want to pass it on.

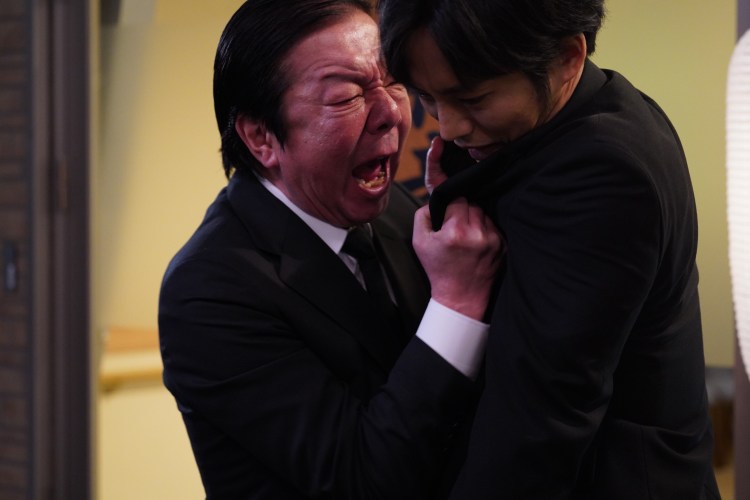

Approached by an intimidating middle-aged man, Izumi (Arata Iura), Kosaka is charged with “looking after” Hijiri in part to find out why she’s been skipping school. She too lost her mother to suicide which her grandfather (Ryo Ishibashi), a mad scientist, has told her is down to a parasite in her brain, the same one that Hijiri has, which eventually drove her to take her own life while it seems simultaneously rejecting the role of his own authoritarianism in which he attempted to force her to have the parasite removed against her will refusing to listen when she insisted her feelings were her own whether he chose to recognise them or not. Hijiri’s quest is similarly one for personal autonomy in the face of her grandfather’s attempts to excise what he sees as abnormal in what amounts to a modern day lobotomy.

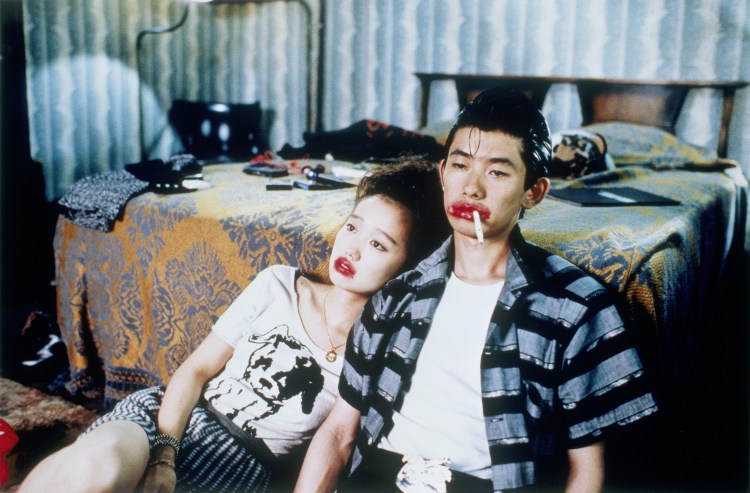

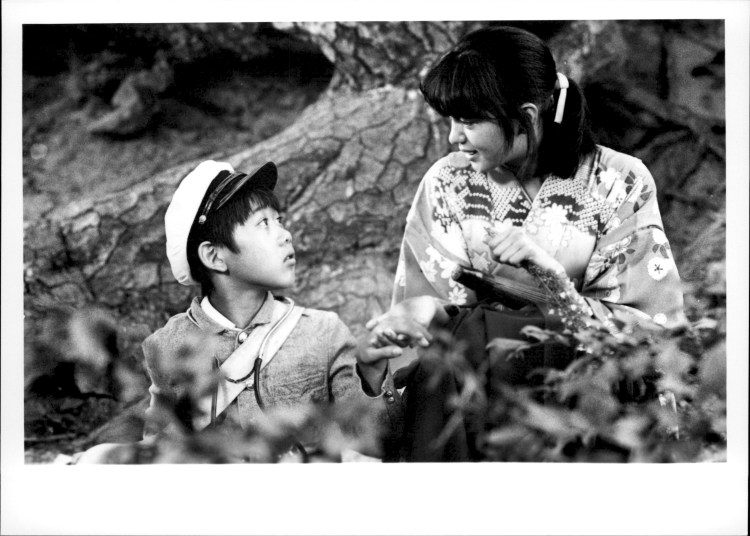

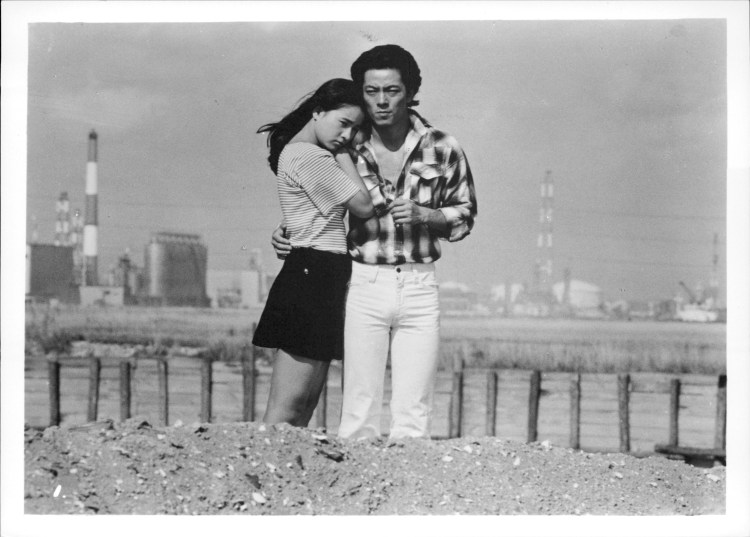

Then again, it’s difficult to argue with the thesis that the relationship between Hijiri and Kosaka is inappropriate given that he is a 27-year-old man and she is a high school girl, which would be one thing if the scientists had not originally forced them together after discovering that Kosaka has the same parasite in his brain and the mutual evolution their pairing would produce would allow them to remove the problematic bug more easily. As the pair hang out together doing “normal” things such as riding public transportation and eating in cafes, gradually the masks and earphones disappear as they give each other the strength to face a hostile environment with an open question mark over whether it’s all down to the bugs or they’ve fallen in love for real. Hijiri’s dilemma is just as in the story she tells of a man who was infected with a parasite that made him love his cat to the exclusion of all else, if they really want to be “cured” or if the price of sacrificing their love and the essence of who they are is worth paying for the right to reenter mainstream society.

As Izumi admits, our bodies are full of bugs and perhaps some of them have more power over us than we’d like think. How much control do you really have over your own biology anyway? Kakimoto’s quirky drama only ever flirts with darkness in Kosaka’s original desire to burn the world out of his intense resentment, and in the mad scientist grandfather’s patriarchal insistence on controlling his granddaughter’s emotional life, removing any hint of what is deemed unconventional to turn her into a perfectly “normal” member of a conservative society. Suggesting that romantic destiny may indeed be akin to a parasitic infection, the film nevertheless comes down on the side of the lovers as they discover solidarity in difference and decide to live their lives the way they see fit parasites or not.

Parasite in Love streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (no subtitles)