Ever get that feeling someone is looking at you, but actually they were looking at someone else? The mismatched cops at the centre of Jonnie To’s black comedy love farce Blind Detective (盲探) seem to encounter this phenomenon more often than most as To and screenwriter Wong Ka-Fai delight in waltzing the audience towards an unexpected conclusion filled with ironic symmetries and persistent doubling as the detectives role-play their way towards truths literal and emotional.

Former policeman Johnston (Andrew Lau Tak-wah) lost his sight after ignoring an eye problem in order to solve his case and has been working as a kind of private detective ever since, looking into cold cases with reward money attached. His old buddies, however, have a habit of exploiting him as they do while trying to stop a series of sulphuric acid attacks unfairly denying him his payout by following him and then technically arresting the criminal “first” so his work doesn’t count. That is however how he first meets agile yet clueless heiress/struggling investigator Ho (Sammi Cheng Sau-man) who lives in a palatial flat left to her by her parents. Regarding him as the god of solving crime, Ho asks Johnston to help her solve a mystery which has plagued her since childhood in the disappearance of Minnie (Lang Yueting), an “unsociable” young girl with no friends who confessed to her that she was worried about becoming the kind of person who could kill for love as her mother and grandmother had done. Little Ho was frightened and stopped hanging out with Minnie even though she stood outside her apartment block just staring up at her in loneliness. Adult Ho feels guilty and ashamed, hoping she can make amends by finding out what happened to her friend.

Like the earlier Mad Detective, Johnston has a special gift and unconventional investigational style which involves a lot of method acting and physical role-play even going to far as to force Ho into getting the same tattoo as one of the victims in a case he’s pursuing. His sightlessness at times allows him to see what others do not, but even his gaze is occasionally misdirected. Ironically enough he’d put off asking out his crush until after he finished his case only to then go blind, while she in turn had put off seeking out hers until after her competition only to lose sight of him, Johnston never realising that when he thought she was looking at him she was actually looking at someone else. The same thing happens with Ho and Minnie, Ho unaware of all the facts never realising there might have been another reason for Minnie’s behaviour. Frequently they look for one thing and find something else, accidentally uncovering a prolific cross-dressing cannibal caveman serial killer living alone in the woods surrounded by skeletons which turns out to have little relationship to their original case save for its tangential link in the killer’s preference for brokenhearted women.

Everything is disguised as something else, the killer of the first case setting up the crime scene to look like his victims killed each other with no one else present while two brokenhearted souls stowaway in wardrobes hoping to reunite with lovers who have rejected them, the second later changing their appearance in order to get a second chance. Love does indeed make you do strange things, the sulphuric acid thrower apparently taking some kind of indirect revenge for his wife’s infidelity as he reveals through a manic phone call first berating and then forgiving her while randomly buying a big bottle helpfully marked “sulphuric acid” from a local supermarket. Yet in this screwball comedy throwback it takes a little while for the oblivious Johnston to realise that he’s fallen for his infatuated new partner who can’t quite be sure he hasn’t fallen for her bank balance instead.

Despite the persistent darkness of serial killings and crimes of passions, Blind Detective is at heart a romantic comedy filled with absurdist, slapstick humour in which the heroes literally tango their way to emotional authenticity, a dance which in part at least requires each partner to look away from the other. To’s delightfully arch comical mystery romance is a tale of misdirected glances and buried truths but eventually allows its equally burdened detectives to step away from their personal baggage and embrace a happier future.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Recent Hong Kong action cinema has not exactly been known for its hero cops. Most often, one brave and valiant officer stands up for justice when all around him are corrupt or acting in self interest rather than for the good of the people. Shock Wave (拆彈專家) sees Herman Yau reteam with veteran actor Andy Lau turning in another fine action performance at 55 years of age as a dedicated, highly skilled and righteous bomb disposal officer who becomes the target of a mad bomber after blowing his cover in an undercover operation. These are universally good cops fighting an insane terrorist whose intense desire for revenge and familial reunion is primed to reduce Hong Kong’s central infrastructure to a smoking mess.

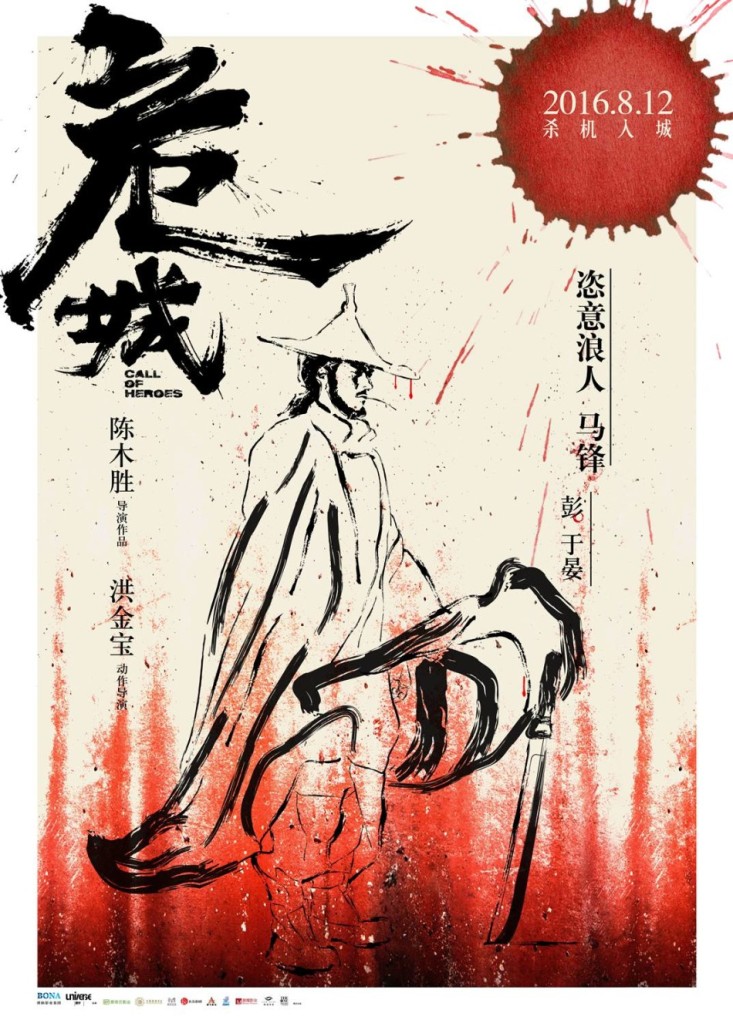

Recent Hong Kong action cinema has not exactly been known for its hero cops. Most often, one brave and valiant officer stands up for justice when all around him are corrupt or acting in self interest rather than for the good of the people. Shock Wave (拆彈專家) sees Herman Yau reteam with veteran actor Andy Lau turning in another fine action performance at 55 years of age as a dedicated, highly skilled and righteous bomb disposal officer who becomes the target of a mad bomber after blowing his cover in an undercover operation. These are universally good cops fighting an insane terrorist whose intense desire for revenge and familial reunion is primed to reduce Hong Kong’s central infrastructure to a smoking mess. A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world.

A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world.