Recently released from prison, a young man discovers that it might be easier to be free behind bars than amid the incredibly homosocial world of urban gangsterdom in Chu Ping’s poignant LGBTQ+ drama, Silent Sparks (愛作歹, ài zuò dǎi). Pua (Akira Huang Guang-Zhi) is a kind of silent spark himself. As the gang boss describes him, he’s too rowdy and can’t keep his cool, which makes him a liability, but he’s also reticent and lonely, not to mention hurt by the seeming rejection when the man he fell in love with in prison ignores him on his release.

There is indeed a latent violence in Pua that hints at his frustration and inability to express himself. When we see him enter prison, he appears as a small boy lost in his own thoughts and silently crying, though he was sent there for breaking a man’s leg in a fight. Though he’s served his time, Pua is still paying off the monetary compensation he owes to the man whose leg he broke and otherwise struggles to get by, which leaves him almost dependent on the gang boss who agrees to take him under his wing as a favour to his mother. It seems that he once knew Pua’s long-absent father, presumably also a gangster, and plays a quasi-paternal role but only half-heartedly in seeing Pua more as a resource to be employed or otherwise an irritating burden he can’t quite seem to shake.

It was the gang boss who asked Mi-ji (Shih Ming-Shuai), his right-hand man, to “look after” Pua in prison. The boss sneers a little, and claims responsibility for saving him, adding that things could have ended up “real nasty” for him inside, by which he means “getting it up your ass”. The irony is that Mi-ji was Pua’s prison lover and Pua is excited about the idea of his release fully expecting to pick up where they left off. But the reunion between them is awkward. Mi-ji is not happy to see him. He speaks tersely and makes it clear he’s not exactly keen for a catch up while keeping one eye on the room in case anyone is getting the right idea. Though Pua continues to pursue him, Mi-ji is avoidant. Perhaps for him, it really was a prison thing that he’s embarrassed about on the outside, whereas Pua is more secure in his sexuality and less afraid of its exposure, only longing to resume the intimacy they once shared.

Mi-ji’s ambivalence hints at the toxic masculinity and entrenched homophobia of the world around them in which homosexuality is not really accepted and “getting it up your ass” is synonymous with defeat and humiliation. The irony is that Pua and Mi-ji were freer in prison where they could embrace their love without shame. Pua is imprisoned within the outside side world by virtue of being unable to be his authentic self, but is also trapped by his socio-economic prospects, which leave him dependent on the underworld and the dubious paternity of the gang boss. Expressing his frustration through violence damns him further in leaving him with mounting debts he can only hope to satisfy through acts of criminality. It is really on this side of the bars that the “real” prison lies, and it’s from this world that Pua longs to be released to return to the prison utopia of his love with Mi-ji.

Still, he cannot really escape his destiny, as his mother keeps reminding having read his tragic gangster fortune and trying to get him to eat rice noodles for 100 days to change his fate only to get her heart broken realising salvation for her son might mean something quite different than she had imagined and also take him away from her. Gritty in its gangland setting and hinting at the connections between political corruption and organised crime Chu’s slow-burn drama makes a hell of the contemporary society in which men like Pua find themselves trapped by toxic masculinities and hierarchal violence under an intensely patriarchal social order that permits them little sense of possibility or the ability to be their authentic selves and true freedom is to be found only within the homosocial world of a more literal “prison”.

Silent Sparks screens at Rio Cinema 5th May as part of this year’s Queer East.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)

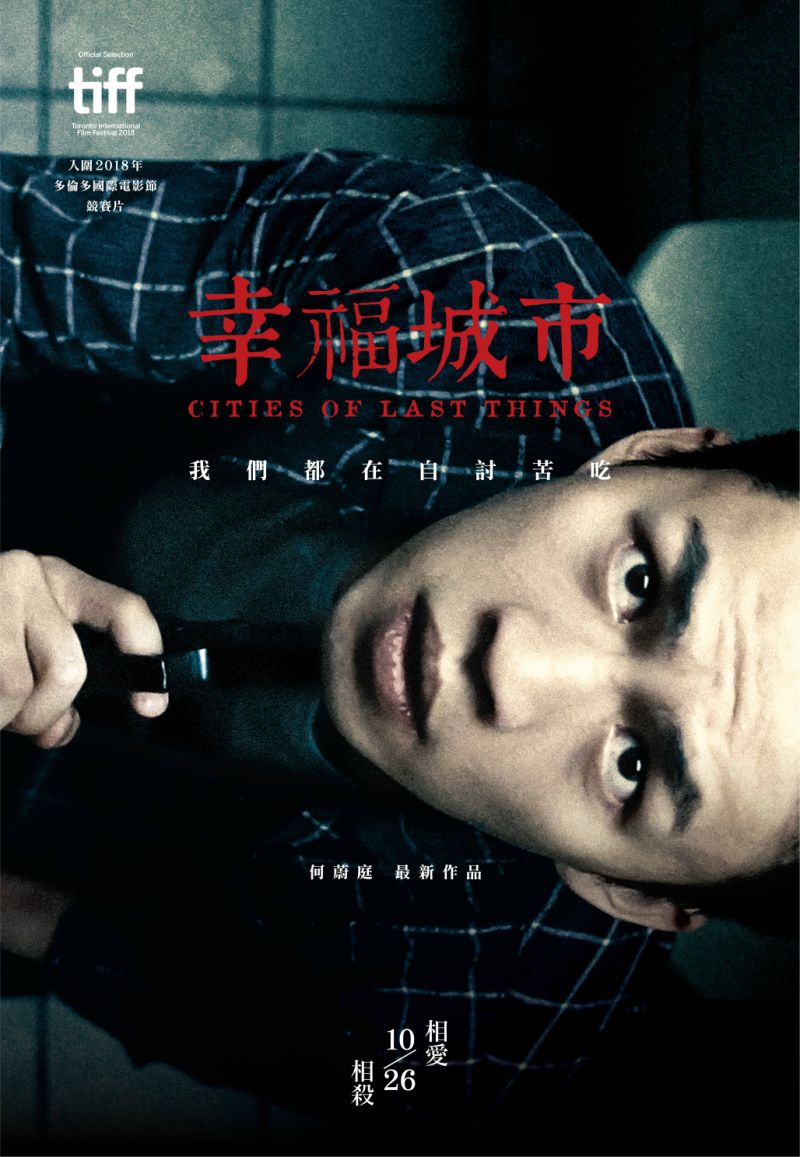

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.

A sense of finality defines the appropriately titled Cities of Last Things (幸福城市, Xìngfú Chéngshì), even as it works itself backwards from the darkness towards the light. Still more ironic, the Chinese title hints at “Happiness City” (neatly subverting Hou Hsiao-hsien’s “City of Sadness”) but that, it seems, is somewhere its hero has never quite felt himself to be. Embittered by a series of abandonments, betrayals, and impossibilities, he grows resentful of the brave new world in which old age has marooned him.