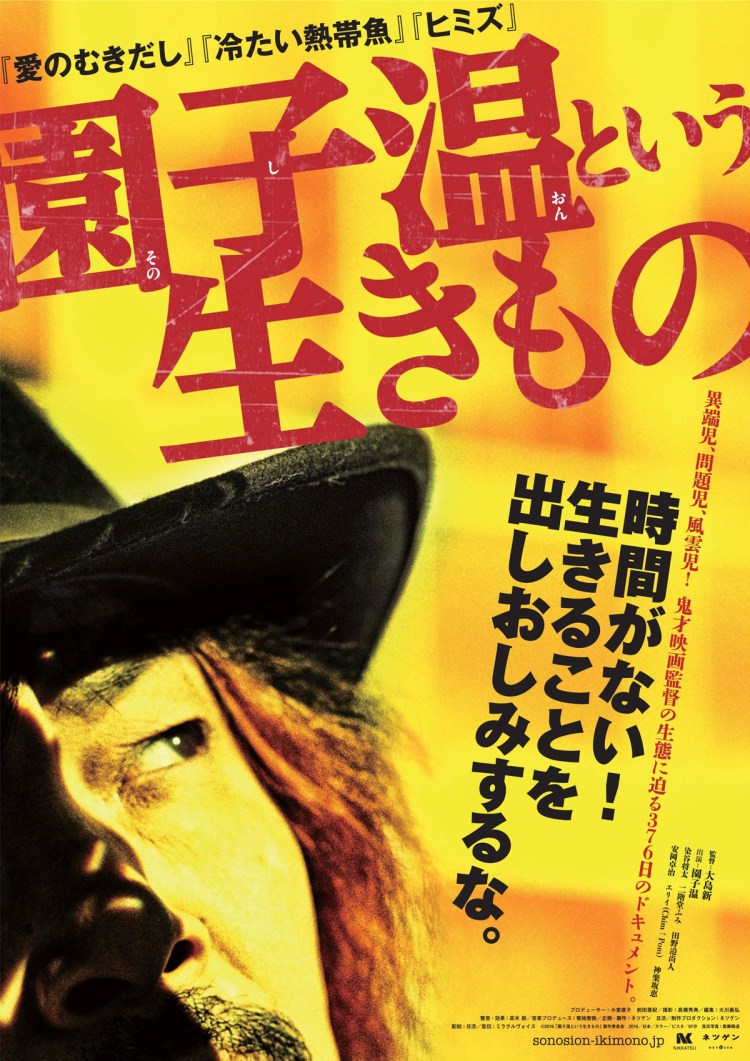

Sion Sono has acquired something of a reputation for controversy. His frequent denouncements of his nation’s cinema in which he sets himself up as a kind of “anti-Ozu” perhaps place him in line with the great 1960s iconoclast Nagisa Oshima who also proclaimed that his distaste for Japanese cinema extended to “absolutely all of it”. Funnily enough, The Sion Sono (園子温という生きもの, Sono Sion to Iu Ikimono) – a documentary exploring the director’s work, is helmed by Oshima’s son, Arata, though he is at pains to show a different side to the artist known as Sion Sono, keying in to the various aways his art reflects his life and vice versa.

Sion Sono has acquired something of a reputation for controversy. His frequent denouncements of his nation’s cinema in which he sets himself up as a kind of “anti-Ozu” perhaps place him in line with the great 1960s iconoclast Nagisa Oshima who also proclaimed that his distaste for Japanese cinema extended to “absolutely all of it”. Funnily enough, The Sion Sono (園子温という生きもの, Sono Sion to Iu Ikimono) – a documentary exploring the director’s work, is helmed by Oshima’s son, Arata, though he is at pains to show a different side to the artist known as Sion Sono, keying in to the various aways his art reflects his life and vice versa.

Shot during 2015, the documentary follows the twin processes of the production of The Whispering Star (one of five films Sono would release that year), and a landmark art exhibition which led straight back to the director’s origins as an avant-garde street protestor with the performance art collective “Tokyo Gagaga”. These joint concerns perhaps highlight a minor conflict in Sono’s working life as he reveals during a casual conversation in referencing the “indecent” work that had been mostly occupying his time over the previous year. Expressing both fear and gratitude for finally gaining the opportunity to work a more personal project (the script for The Whispering Star had been written almost 20 years previously), Sono jokes that he’ll finally be getting “clean” only to immediately relapse by making The Virgin Psychics – the big screen adaptation of a sci-fi TV series he had also directed which largely consisted of lewd juvenile humour.

To rewind slightly, Sion Sono had been making films for almost 20 years before getting mainstream festival attention in the early 2000s with Suicide Club and Noriko’s Dinner Table. His profile was further enhanced by the international success of serial killer thriller Cold Fish and the Venice recognition of Himizu even if it’s the 4-hour epic and sleeper cult hit Love Exposure which has become synonymous with his name for many Western viewers. In the opening to camera interview, Sono is asked about his “controversial” image and overseas success to which he laments that Japanese audiences are wary of anything unconventional and particularly allergic to the “wacky Japan” tag that often dogs attempts to sell Japanese media overseas. Unorthodox views or ways of working are unwelcome, as are those who live in unorthodox ways.

Perhaps for these reasons, 2015 saw Sono diving headfirst into the populist with mixed results. Avowing at a press conference that he believes in “quantity over quality”, Sono commits himself to simply making films hoping some of them might turn out OK. Thus his more straightforwardly commercial projects, Shinjuku Swan for example, are often filled with unconventional ideas but perhaps lack the sense of attack found in his more potent work, covering a lack of substance with intentional boldness. The Whispering Star, as we see, brings him full circle. Picking up the Tarkovskian influences seen in one of his most impressive early features – the sadly neglected The Room, the minimalist sci-fi drama also encompasses his compassion for the people of Fukushima whose ongoing strife has become a recurrent concern from the ruined landscapes of Himizu to the more directly political Land of Hope.

It’s this essential sense of compassion which Oshima’s documentary seems keenest to capture. Through in person interviews with some of Sono’s frequent collaborators including Himizu’s Shota Sometani and Fumi Nikaido who characterise the director as an eccentric uncle, and his actress wife Megumi Kagurazaka (the lead in Whispering Star) who breaks down in tears remembering the sometimes difficult days of their earlier collaborations, Sono’s art emerges less as an attack on a conservative society than an exercise in melancholy sarcasm that, at heart, believes the world can be better than it is. A friend of his puts this quality best when she (part correcting herself for triteness) states that despite his sometimes controversial approach, she believes he just wants everyone to be happy and is attempting to transcend his own ideas in order to cut through to something new.

Then again perhaps Sono puts this best himself in accidentally citing a life philosophy. Art is not about good and bad; life is not about good and bad. “Paint! Express! Live!” – what better encapsulation of an artist’s credo could there be?

Released by Third Window Films as part of a double feature pack with The Whispering Star.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has taken a turn for the romantic in his later career. Both 2013’s Real (リアル 完全なる首長竜の日, Real: Kanzen Naru Kubinagaryu no Hi) and

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has taken a turn for the romantic in his later career. Both 2013’s Real (リアル 完全なる首長竜の日, Real: Kanzen Naru Kubinagaryu no Hi) and

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

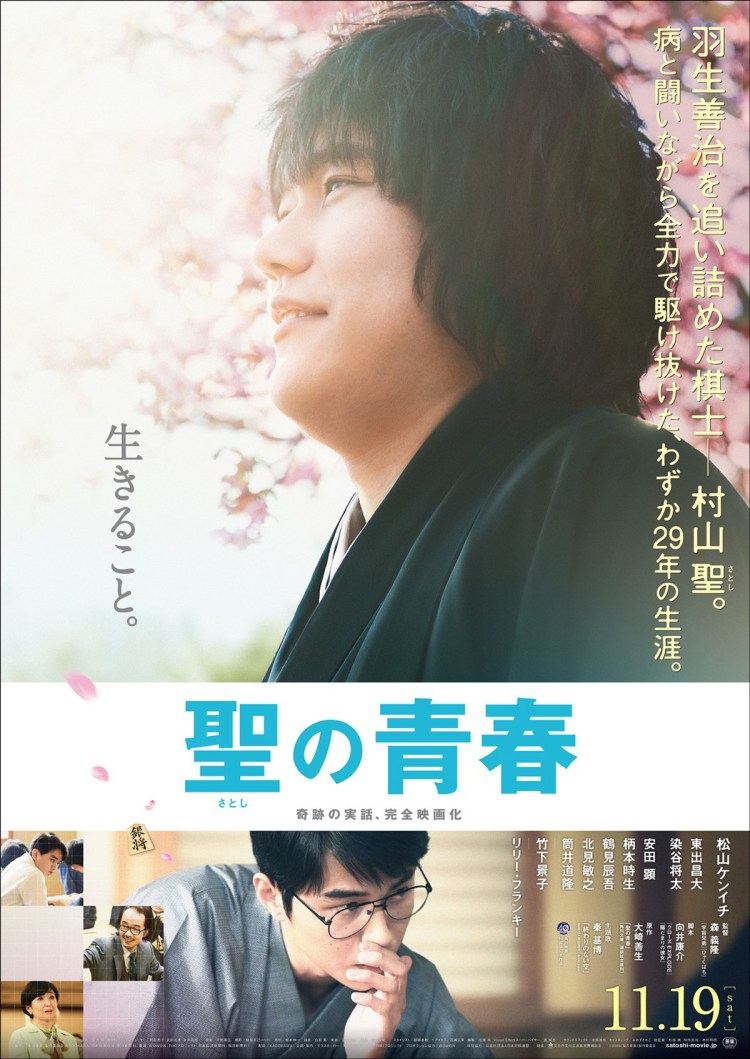

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

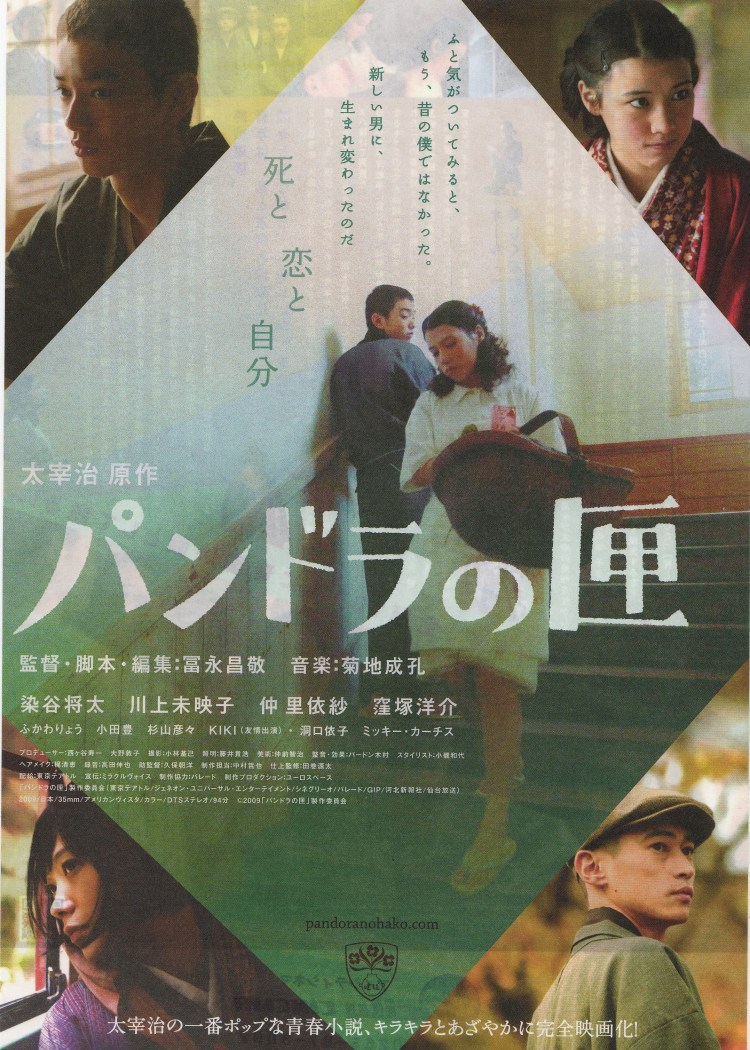

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper. Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic  Review the concluding chapter of Takashi Yamazaki’s Parasyte live action movie (寄生獣 完結編, Kiseiju Kanketsu Hen) first published by

Review the concluding chapter of Takashi Yamazaki’s Parasyte live action movie (寄生獣 完結編, Kiseiju Kanketsu Hen) first published by

Kabukicho Love Hotel (さよなら歌舞伎町, Sayonara Kabukicho), to go by its more prosaic English title, is a Runyonesque portrait of Tokyo’s red light district centered around the comings and goings of the Hotel Atlas – an establishment which rents by the hour and takes care not to ask too many questions of its clientele. The real aim of the collection of intersecting stories is more easily seen in the original Japanese title, Sayonara Kabukicho, as the vast majority of our protagonists decide to use today’s chaotic events to finally get out of this dead end town once and for all.

Kabukicho Love Hotel (さよなら歌舞伎町, Sayonara Kabukicho), to go by its more prosaic English title, is a Runyonesque portrait of Tokyo’s red light district centered around the comings and goings of the Hotel Atlas – an establishment which rents by the hour and takes care not to ask too many questions of its clientele. The real aim of the collection of intersecting stories is more easily seen in the original Japanese title, Sayonara Kabukicho, as the vast majority of our protagonists decide to use today’s chaotic events to finally get out of this dead end town once and for all.