“Freedom is disappearing from our world. Everyone rise up!” screams an accidental revolutionary having achieved a kind of self-actualisation in wresting the leading role not only in the film within the film but in the film itself in an act of characteristically meta Sion Sono playfulness. Harking back to the earlier days of his more recently prolific career, Red Post on Escher Street (エッシャー通りの赤いポスト, Escher dori no akai post) is perhaps a thinly veiled though affectionate attack on the mainstream Japanese cinema industry, a defence not only of “jishu eiga” but a “jishu” life in the meditation that a crowd is composed of many faces in which we are all simultanteously extra and protagonist.

In a sense perhaps Sono’s stand-in, the director at the film’s centre, Tadashi Kobayashi (Tatsuhiro Yamaoka), is a festival darling who made his name with a series of critically acclaimed independent films but has since been dragged towards the mainstream while forced into a moment of reconsideration following the sudden death of his muse and lover. Kobayashi’s ambition is to produce another DIY film of the kind that first sparked his creative awakening, but it’s clear from the get go that his desires and those of his backers to not exactly match. Middle man producer Muto (Taro Suwa), sporting a sling and broken leg after being beaten up by the jealous boyfriend of a starlet he’d been “seeing”, is under strict instructions to ensure Kobayashi casts names and most particularly the series of names the studio want. To convince him, they go so far as to have the established “stars” (seemingly more personalities than actresses) join the open auditions at which the director hoped to find fresh faces, hoping he can be persuaded to cast them instead. The irony is that the studio want Kobayashi’s festival kudos, but at the same time deny him the freedom to make the kind of films that will appeal to the international circuit, the director frequently complaining the producers keep mangling his script with their unhelpful notes.

A handsome young man, Kobayashi has also inspired cult-like devotion among fans including a decidedly strange group of devotees branding themselves the “Kobayashi True Love Club” who each wear Edwardian-style white lace dresses and straw hats while singing a folksong everywhere they go. Nevertheless, most of the hopefuls are ordinary young women with an interest in performing or merely for becoming famous. Their stories are the story, a series of universes spinning off from the central spine from a troupe kimono’d actresses performing a play about female gamblers, to a young widow taking on the mission of making her late husband’s acting dreams come true, and a very intense woman with an extremely traumatic past. The audition speech finds each of the hopefuls vowing to drag their true love back from “the crowd” into which he fears he is dissolving, only for them later to save themselves by removing their “masks” to reclaim their individual identity and agency as protagonists in their own lives rather than passively accept their relegation to the role of extra.

Then again, there are those who wilfully embrace the label such as a faintly ridiculous old man who commands near cult-like adoration from his disciples of professional supernumeraries for his ability to hog the screen even if his less than naturalistic acting is at best a distraction from the main action. Without extras, he points out, the screen would become a lonely place, lacking in life and energy though he at least seems to be content to occupy a liminal space never desiring the leading role but seizing his 15 seconds of fame as a prominent bystander. Others however are not, determined to elbow aside the vacuous leading players and reclaim their space. Subtly critiquing the seamier ends of the industry from the lecherous producers who always seem to be draped with a young woman eager for fame and fortune, to the machinations of star makers and manipulations of talentless celebrities, the film makes an argument for sidestepping an infinitely corrupt system in suggesting the jishu way is inherently purer but nevertheless ends on a note of irony as its defiant act of guerrilla filmmaking is abruptly shutdown by the gloved hand of state authority.

Red Post on Escher Street streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Sion Sono has been especially prolific of late, though much of his recent output has leant towards the populist rather than the art house. Having garnered a reputation for vulgar excess over the last twenty years or so, Sono returns to his Tarkovskian roots with The Whispering Star (ひそひそ星, Hiso Hiso Boshi) – a contemplative exercise in stillness which has more in common with

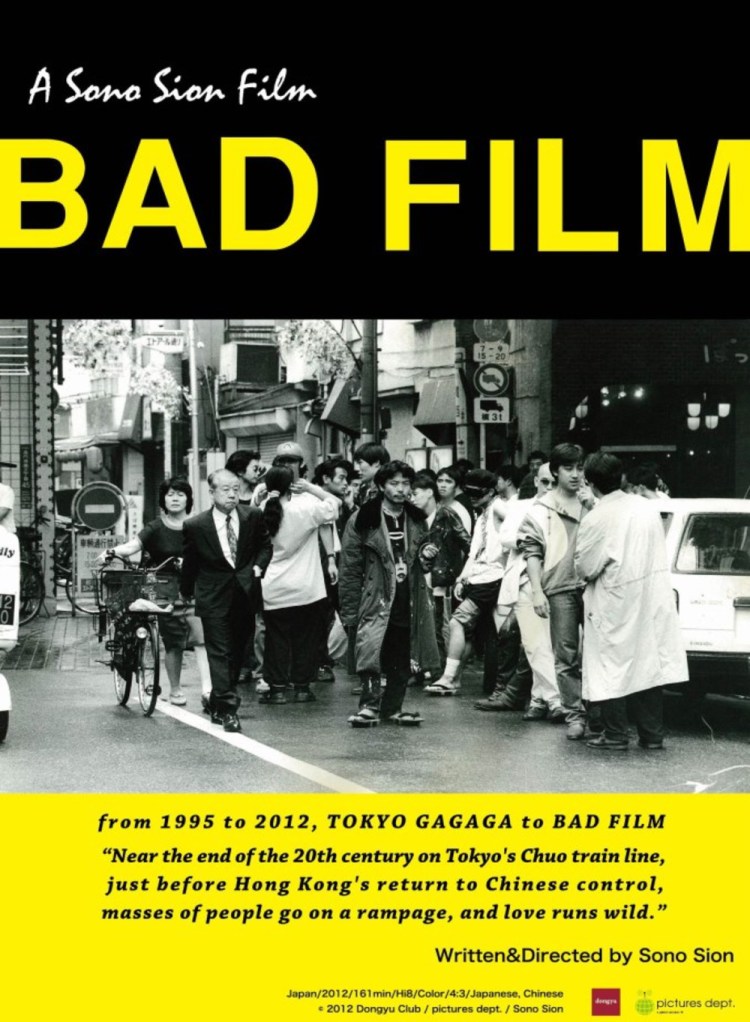

Sion Sono has been especially prolific of late, though much of his recent output has leant towards the populist rather than the art house. Having garnered a reputation for vulgar excess over the last twenty years or so, Sono returns to his Tarkovskian roots with The Whispering Star (ひそひそ星, Hiso Hiso Boshi) – a contemplative exercise in stillness which has more in common with  The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

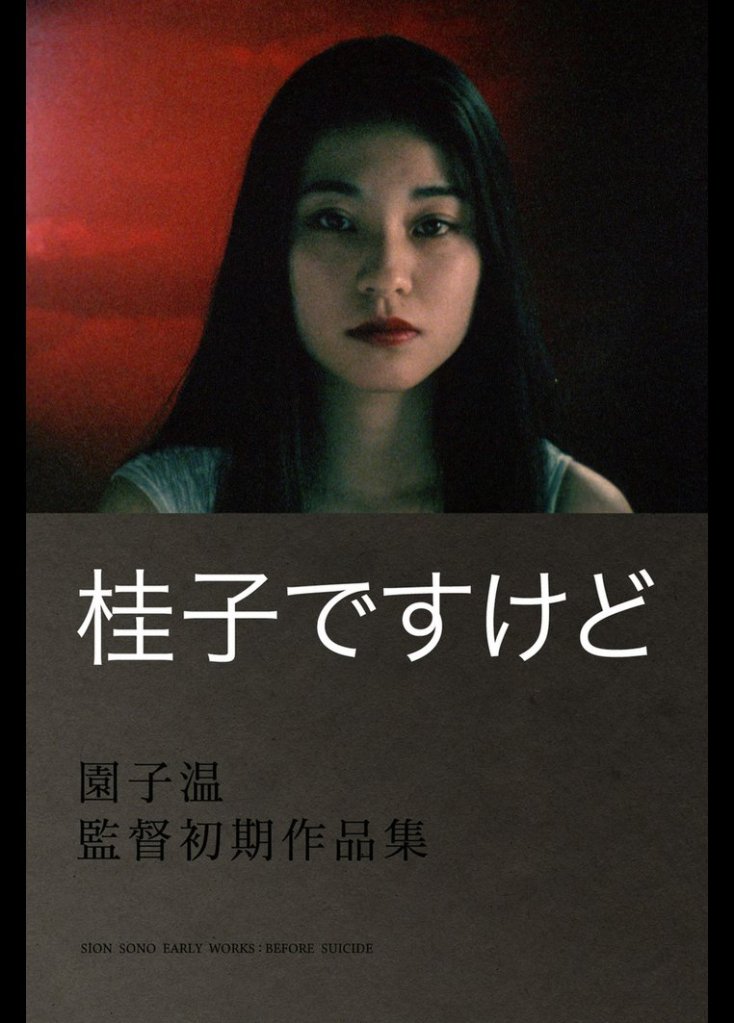

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth.

I was 21 years when I wrote this song, I’m 22 now but I won’t be for long…the leaves that are green are turning to brown for the heroine of Keiko Desu Kedo (桂子ですけど, “I am Keiko”). Approaching her 22nd birthday and with the recent death of her father ever present in her mind, she’s begun to feel the passage of time even more keenly. She doesn’t want to miss out on or forget anything so she’s going to share with us the last three weeks of her 21st year on Earth.

Enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry Sion Sono has always been prolific but recent times have seen him pushing the limits of the possible and giving even Takashi Miike a run for his money in the release stakes. Indeed, Takashi Miike is a handy reference point for Sono’s take on Shinjuku Swan (新宿スワン) – an adaptation of a manga which has previously been brought to the small screen and is also scripted by an independent screenwriter rather than self penned in keeping with the majority of Sono’s directing credits. Oddly, the film shares several cast members with Miike’s Crows Zero movies and even lifts a key aesthetic directly from them. In fact, there are times when Shinjuku Swan feels like an unofficial spin-off to the Crows Zero world with its macho high school era tussling relocated to the seedy underbelly of Kabukicho. Unfortunately, this is somewhat symptomatic of Sono’s failure, or lack of will, to add anything particularly original to this, it has to be said, unpleasant tale.

Enfant terrible of the Japanese film industry Sion Sono has always been prolific but recent times have seen him pushing the limits of the possible and giving even Takashi Miike a run for his money in the release stakes. Indeed, Takashi Miike is a handy reference point for Sono’s take on Shinjuku Swan (新宿スワン) – an adaptation of a manga which has previously been brought to the small screen and is also scripted by an independent screenwriter rather than self penned in keeping with the majority of Sono’s directing credits. Oddly, the film shares several cast members with Miike’s Crows Zero movies and even lifts a key aesthetic directly from them. In fact, there are times when Shinjuku Swan feels like an unofficial spin-off to the Crows Zero world with its macho high school era tussling relocated to the seedy underbelly of Kabukicho. Unfortunately, this is somewhat symptomatic of Sono’s failure, or lack of will, to add anything particularly original to this, it has to be said, unpleasant tale.