An earnest young man, grieving son, and feisty princess team up to stop the evil Demon Society from becoming all-powerful rulers of their land in an adaptation of classic Taiwanese comic book Shiro – Hero of Heroes (諸葛四郎 – 英雄的英雄, Zhūgě Sìláng – yīngxióng de yīngxióng). Created by Yeh Hong-Chia in the late 1950s, the series has become a nostalgic touchstone for generations of children and is about to reach new ones with a feature-length 3D CGI animation following Zhuge Shiro (Wang Chen-hua) on another exciting adventure to reunite the magical Dragon and Phoenix swords and stop their awesome power from falling into the wrong hands.

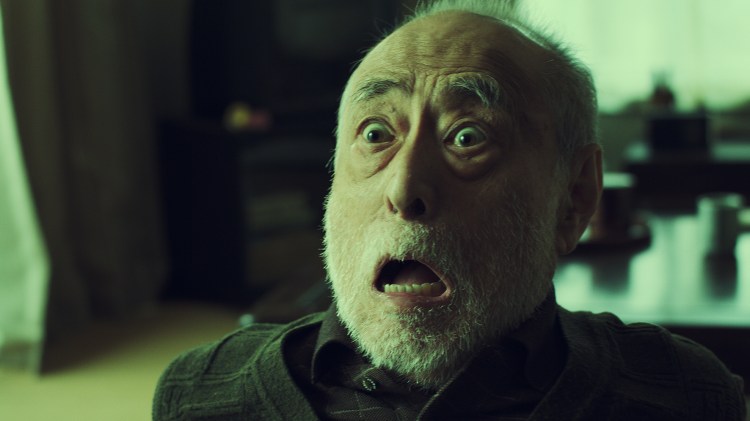

Unfortunately the Dragon Sword has already been lost, much to the king’s regret. When Demon Society raid the palace during a festival and place a mask over the princess’ face, the king puts the land on lockdown and summons the nation’s locksmiths to try and free her only to realise there’s no way to unpick Demon Society’s diabolical locks without giving in to their demands to surrender the Phoenix Sword. Luckily hero of heroes Zhuge Shiro just happens to be in town on the invitation of his locksmith uncle and pledges to help the king salvage his fracturing relationship with his daughter who resents his hesitation to exchange the sword for her wellbeing and make sure Demon Society doesn’t get its hands on the swords’ unleashed power.

Though this is in many ways a tale aimed at younger audiences, the incredibly witty script moving to the rhythms of traditional opera includes a series of meta jokes for grownups from a silly reference to a limited edition dart and workplace exploitation to subtle digs at societal authoritarianism along with a small cameo from a wandering cartoonist whose work is censored by the powers that be. Having faced Demon Society several times before, Zhuge Shiro is a pure hearted young man wise beyond his years with a strong sense of justice. His first act of goodness is standing up to an officious guard, General Shan, who won’t let a worried father with a sick child enter the town to find a doctor, while he soon earns the respect of the king through his compassion and emotional intelligence in trying to explain the king’s dilemma to the princess. He does however engage in a little sexism which the princess herself is quick to push back against, pointng out that she’s a skilled fighter herself and does not need protecting but will be joining him on this mission whether he likes it or not.

Similarly, Zhuge Shiro gains another comrade in Zhen Ping (Chiang Tieh-Cheng) who is originally under the misapprehension that Zhuge Shiro is responsible for his father’s death only to later realise it was all the fault of Demon Society. To reunite the swords and save the kingdom, the trio find themselves battling through the villain’s booby trapped lair and discovering that the swords’ power lies in a different place than they first might have assumed, one Demon Society is largely unable to appreciate and therefore to benefit from even if they had managed to hold both swords in tandem. In other words, it’s brotherhood and justice which eventually enable the trio to prosper while the bumbling masked demons only make fools of themselves in their intense greed and villainy.

Staying close to the aesthetic of the comic book, the film’s highly stylised designs closely match those of the original characters from back in the late 1950s if perhaps a little cuter and rounder in keeping with contemporary CGI animation while it moves to a comic beat inspired by traditional opera interspersed with a few song and dance numbers and exciting martial arts fight scenes as the trio face off against the minions of Demon Society while standing up for justice. Just as the king learns the real meaning of treasure, the trio discover a brotherly bond and a new mission to rid the land of the evils of Demon Society while accepting that even villains can change their ways and should be allowed a chance to redeem themselves, and those who may seem obviously villainous might be alright on the inside. In any case, Zhuge Shiro embarks on what could be the first of many adventures in charming style taking down the bad guys with good humour and righteousness fuelled by the power of friendship.

Shiro – Hero of Heroes screens in Chicago on Oct. 23 as part of the 15th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Original trailer (English subtitles)