What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of Judge for an Iwai-inflected tale of life thrown into sharp relief by impending death. Less a maudlin meditation on the will to life, If Cats Disappeared from the World (世界から猫が消えたなら, Sekai kara Neko ga Kieta nara) is an existential journey into the mind of a man who believed himself an irrelevance, beloved by no one and living an unfulfilling existence, only to rediscover his essential place in the world at the moment he’s about to vacate it.

What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of Judge for an Iwai-inflected tale of life thrown into sharp relief by impending death. Less a maudlin meditation on the will to life, If Cats Disappeared from the World (世界から猫が消えたなら, Sekai kara Neko ga Kieta nara) is an existential journey into the mind of a man who believed himself an irrelevance, beloved by no one and living an unfulfilling existence, only to rediscover his essential place in the world at the moment he’s about to vacate it.

An unnamed 30 year old postman (Takeru Satoh) has a freak bicycle accident and is subsequently informed that he has an aggressive brain tumour which may take his life at any moment. Following this traumatic news, the postman returns home to discover his own doppelgänger there, waiting for him. The doppelgänger tells him that he will die tomorrow, unless the postman accepts the offer the doppelgänger is about to make him. There are too many unnecessary and irritating things in the modern world, in return for postponing the postman’s death sentence, the doppelgänger will erase one thing from human society – if only the postman will agree.

As in many similarly themed films of recent times, memories are stored not on hard drives or even in notebooks but in seemingly irrelevant objects with unexpected sentimental value. Quite literally “material culture”, it is the objects which provide the path back to the past and their destruction represents not only the severing of a connection but a kind of erasure of the past itself.

The doppelgänger sets about deleting various items at will which might previously have seemed irrelevant to the postman but turn out to have fundamental connections to the most important aspects of his life. The first item to go is phones (all phones, not just mobiles) which reminds him of his first love (Aoi Miyazaki) whom he met after she dialled a wrong number and recognised the score to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis which he happened to be watching at the time. Phones and movies – the second item on the doppelgänger’s hit list, brought the two together but it couldn’t have happened without the cinephile best friend (Gaku Hamada) the postman met at university who has been his movie mule ever since. Delete the phone and the movies and the postman loses his first love and best friend to win the right to live on alone for just one day. Cats turn out to have an even more essential role in the postman’s life, one which is painful for him to consider but impossible to ignore.

The protagonist’s occupation, which becomes his name and defining feature, is an ironic one. A mere conveyor of items charged with other people’s memories. he feels like an empty vessel, trapped in an existence devoid of meaning. Yet his strange doppelgänger pushes him to reconsider his place in the world, re-entering a sphere he had long absented himself from. Remembering long forgotten yet life changing holidays with the love of his life or finally coming to understand the silent signs of devotion in his emotionally distant father (Eiji Okuda), the postman finally writes his own letter, the first and last of his life, answering the questions he never wanted to ask.

Finally learning to accept his fate, the postman rediscovers the meaning of life. He may leave with regrets and dreams never to be fulfilled, but wants to believe his life has made a difference, meant something at least. Only as he’s about to leave it does the postman feel himself connected to the world, finally noticing the beauty all around him.

On learning of his condition, the postman’s first thoughts turn to all the movies he’ll never see and the books he’ll never read. The doppelgänger’s determination to delete the movies provokes a quietly passionate defence of the arts but, apparently, they are not worth dying for. Nagai films with a low-key dreaminess as magical realism mixes with wistful nostalgia in the melancholy world of a man who has no future finally falling in love with the past. A celebration of the interconnectedness of all things in a world of increasing isolation, If Cats Disappeared from the World advises you make the most of your time, making the difference only you can make before it’s too late.

Hong Kong trailer (English subtitles)

Fear of “broadcasting” is a classic symptom of psychosis, but supposing there really was someone who could hear all your thoughts as clearly as if you’d spoken them aloud, how would that make you feel? The shy daydreamer at the centre of The Kodai Family (高台家の人々, Kodaike no Hitobito) is about to find out as she becomes embroiled in a very real fairytale with a handsome prince whose lifelong ability to read minds has made him wary of trying to form genuine connections with ordinary people. Walls come down only to jump back up again when the full implications become apparent but there are taller walls to climb than that of discomfort with intimacy including snobby mothers and class based insecurities.

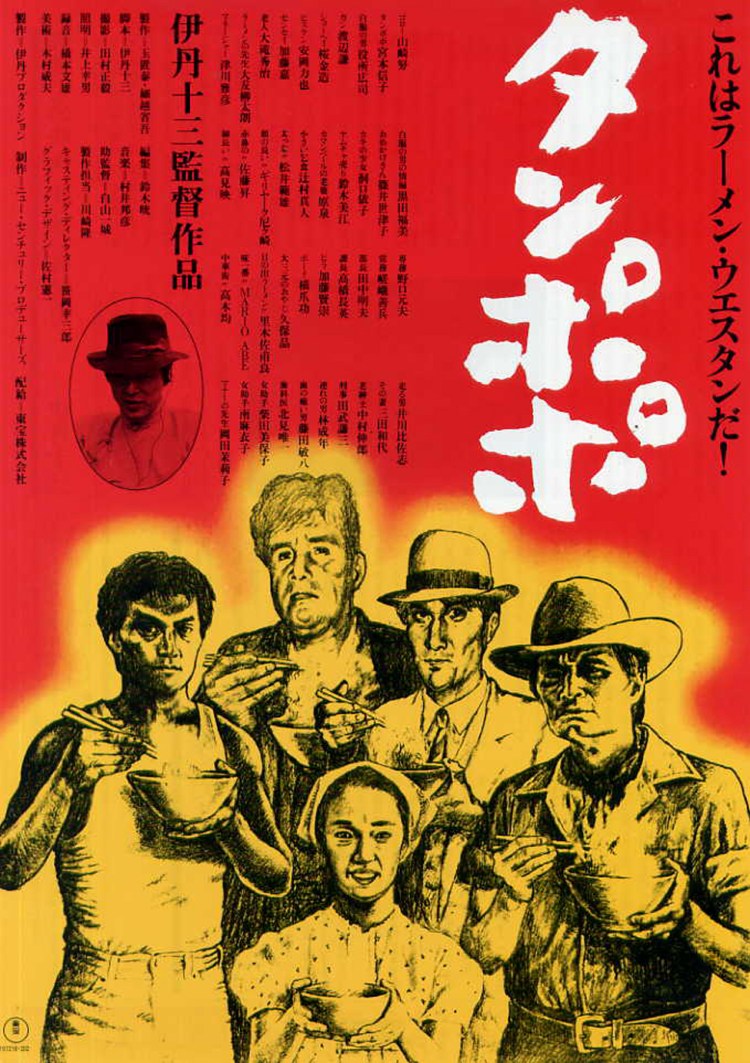

Fear of “broadcasting” is a classic symptom of psychosis, but supposing there really was someone who could hear all your thoughts as clearly as if you’d spoken them aloud, how would that make you feel? The shy daydreamer at the centre of The Kodai Family (高台家の人々, Kodaike no Hitobito) is about to find out as she becomes embroiled in a very real fairytale with a handsome prince whose lifelong ability to read minds has made him wary of trying to form genuine connections with ordinary people. Walls come down only to jump back up again when the full implications become apparent but there are taller walls to climb than that of discomfort with intimacy including snobby mothers and class based insecurities. Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Back in the real world, politics has never felt so unfunny. This latest slice of unlikely political satire from Japan may feel a little close to home, at least to those of us who hail from nations where it seems perfectly normal that the older men who make up the political elite all attended the same school and fully expected to grow up and walk directly into high office, never needing to worry about anything so ordinary as a career. Taking this idea to its extreme, elite teenager Teiichi is not only determined to take over Japan by becoming its Prime Minister, but to start his very own nation. In Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High (帝一の國, Teiichi no Kuni) teenage flirtations with fascism, homoeroticism, factionalism, extremism – in fact just about every “ism” you can think of (aside from altruism) vie for the top spot among the boys at Supreme High but who, or what, will finally win out in Teiichi’s fledging, mental little nation?

Back in the real world, politics has never felt so unfunny. This latest slice of unlikely political satire from Japan may feel a little close to home, at least to those of us who hail from nations where it seems perfectly normal that the older men who make up the political elite all attended the same school and fully expected to grow up and walk directly into high office, never needing to worry about anything so ordinary as a career. Taking this idea to its extreme, elite teenager Teiichi is not only determined to take over Japan by becoming its Prime Minister, but to start his very own nation. In Teiichi: Battle of Supreme High (帝一の國, Teiichi no Kuni) teenage flirtations with fascism, homoeroticism, factionalism, extremism – in fact just about every “ism” you can think of (aside from altruism) vie for the top spot among the boys at Supreme High but who, or what, will finally win out in Teiichi’s fledging, mental little nation? Hiroshi Nishitani has spent the bulk of his career working in television. Best known for the phenomenally popular Galileo starring Masaharu Fukuyama which spawned a number of big screen spin-offs including an adaptation of the series’ inspiration The Devotion of Suspect X and

Hiroshi Nishitani has spent the bulk of his career working in television. Best known for the phenomenally popular Galileo starring Masaharu Fukuyama which spawned a number of big screen spin-offs including an adaptation of the series’ inspiration The Devotion of Suspect X and

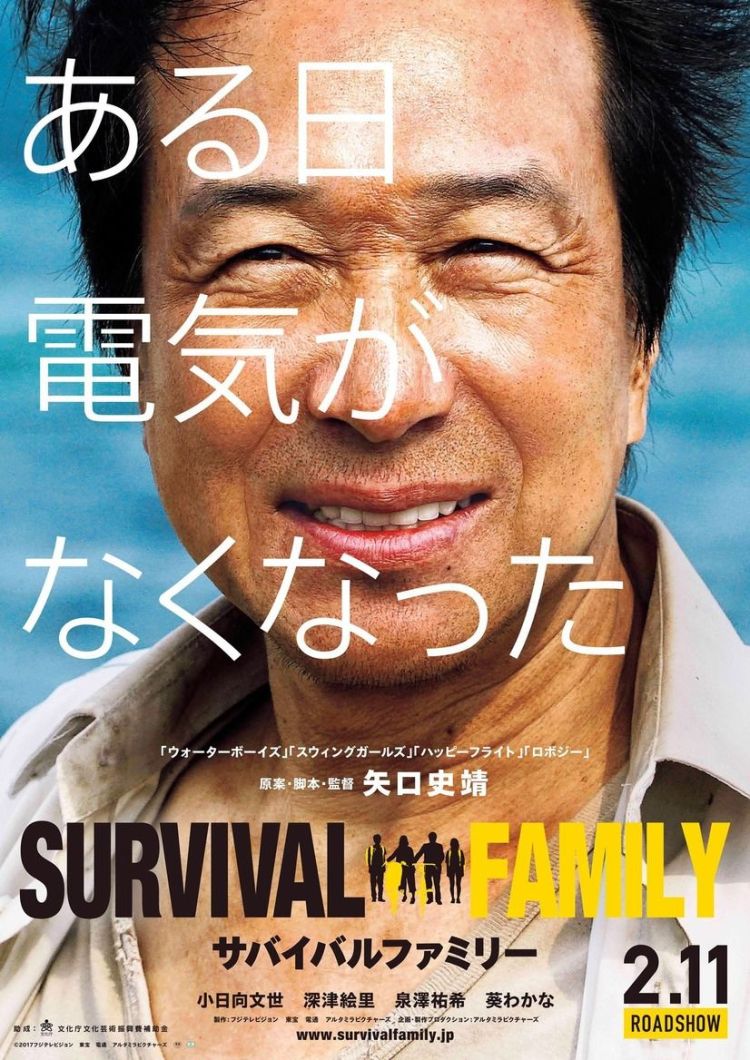

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world. Placed between

Placed between  1969. Man lands on the moon, the cold war is in full swing, and Star Trek is cancelled prompting a mass write-in campaign from devoted sci-fi enthusiasts across America. The tide was also turning politically as the aforementioned TV series’ utopianism came to gain ground among liberal thinking people who rose up to oppose war, racial discrimination and sexism. It was in this year that Godzilla creators Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya brought their talents to America with a very contemporary take on science fiction in Latitude Zero (緯度0大作戦, Ido Zero Daisakusen). Starring Hollywood legend Joseph Cotten, Latitude Zero gives Jules Verne a new look for the ‘60s filled with solid gold hotpants and bulletproof spray tan.

1969. Man lands on the moon, the cold war is in full swing, and Star Trek is cancelled prompting a mass write-in campaign from devoted sci-fi enthusiasts across America. The tide was also turning politically as the aforementioned TV series’ utopianism came to gain ground among liberal thinking people who rose up to oppose war, racial discrimination and sexism. It was in this year that Godzilla creators Ishiro Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya brought their talents to America with a very contemporary take on science fiction in Latitude Zero (緯度0大作戦, Ido Zero Daisakusen). Starring Hollywood legend Joseph Cotten, Latitude Zero gives Jules Verne a new look for the ‘60s filled with solid gold hotpants and bulletproof spray tan.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai. Ishiro Honda returns to outer space after The Mysterians with another dose of alien paranoia in the SFX heavy Battle in Outer Space (宇宙大戦争, Uchu Daisenso). Where many other films of the period had a much more ambivalent attitude to scientific endeavour, Battle in Outer Space paints the science guys as the thin white line that stands between us and annihilation by invading forces wielding superior technology. Far from the force which destroys us, science is our salvation and the skill we must improve in order to defend ourselves from hitherto unknown threats.

Ishiro Honda returns to outer space after The Mysterians with another dose of alien paranoia in the SFX heavy Battle in Outer Space (宇宙大戦争, Uchu Daisenso). Where many other films of the period had a much more ambivalent attitude to scientific endeavour, Battle in Outer Space paints the science guys as the thin white line that stands between us and annihilation by invading forces wielding superior technology. Far from the force which destroys us, science is our salvation and the skill we must improve in order to defend ourselves from hitherto unknown threats.