With the Olympics still two years away, the Japanese economy had begun to improve by 1962 and the salaryman dream was on the horizon for all. But for young couples trying to make it in the post-war society things were perhaps far from easy and having more to want coupled with the anxieties of a newly consumerist society only left them with additional burdens. A surprisingly moving evocation of the cycle of life, Kon Ichikawa’s Being Two Isn’t Easy (私は二歳, Watashi wa Nisai) is as much about the trials and tribulations of its toddler hero’s parents as they try to navigate their new roles in a world which now seems fraught with potential dangers.

This difference in perspective is brought home in the opening sequence in which soon-to-be two Taro (Hiro Suzuki) recalls his own birth in a slightly creepy voiceover, lamenting his mother cooing over him excited that he is smiling for her though he is not yet able to focus and has no idea the vague shadow above him is his mother or even what a mother is. His smiling is simply involuntary muscle contraction as he learns how to manipulate his body. Nevertheless, little Taro is a definite handful taxing his poor mother Chiyo (Fujiko Yamamoto) with frequent attempts to escape, managing to get out of the apartment and start climbing the stairs the instant she’s turned her back. “Always finding fault, that’s why grown-ups are unhappy” Taro complains, irritated that even though he’s quite proud of himself for figuring out not only how to undo the screws on his playpen but the string his parents had tied around it for extra protection, he’s not received any praise or congratulation and it feels like they’re annoyed with him.

The landlord alerted by the commotion somewhat ironically remarks that “Japanese houses are best for Japanese babies” (being at least usually all on one level even if they also sometimes have their share of dangerously precipitous staircases), implicitly criticising the new high rise society. There do indeed seem to be dangers everywhere. Another baby playing on the balcony eventually falls because the screws are rusty on the railings only to be caught by a passing milkman in what seems to be an ironic nod to the film’s strange fascination with the new craze in cow’s milk to which Taro’s father Goro (Eiji Funakoshi) attributes Westerners’ ability to grow up big and strong. Taro does seem to get sick a lot, the doctor more or less implying that his sickliness is in part transferred anxiety from an overabundance of parental love. Visited by her older sister who lives on a farm in the country and has eight children, Chiyo becomes broody for a second baby (though not another six!) but Goro isn’t so sure, not just because of the additional expense or the fact that their danchi apartment is already cramped with the two of them and a toddler, but reflecting that he already lives in a world of constant fear why would you want to double it worrying about two kids instead of one?

Nevertheless, Goro is certainly a very “modern” man. He helps out with the housework and is an active father, taking on his share of the childcare responsibilities and very invested in his son. He accepts that his wife also “works” even if he also insists it’s not the same because she doesn’t have to bow to Taro and is not subject to the petty humiliations of the salaryman life. Tellingly, this changes slightly when the couple end up leaving the danchi for a traditional Japanese home to move in with Goro’s mother after his brother gets a job transfer. Grandma (Kumeko Urabe) is actively opposed to him helping out around the house, viewing it as distasteful and unmanly not to say a black mark against Chiyo for supposedly not proving up to her wifely duties. Living with Grandma also introduces a maternal power struggle under the older woman’s my house my rules policy which extends to criticising Chiyo’s parenting philosophy not to mention refusing to trust “modern technology” by insisting on rewashing everything that’s been through the washing machine by hand.

Yet when Taro becomes sick again it’s perhaps Grandma who has a surprisingly consumerist view of medical care. Exasperated by the couple’s failure to get Taro to take his medicine she offends the doctor by insisting on him having an injection as if you haven’t really been treated without one. Eventually she takes him to another clinic where they get on a conveyor belt of doctoring, rushed through from a disinterested receptionist to a physician who yells “bronchitis” to a nurse who violently sticks the baby in the arm. After that Taro vows never to trust grown-ups, though Grandma only gives in when she realises injections are not an instacure and didn’t do any good.

For all that however there’s a poignancy in Taro’s reflecting on his birthday cake with its two candles that Grandma’s must have many more and in fact be brighter than the moon with which he has a strange fascination. He’s just turning two. He used to be a baby but now he’s a big boy and soon he’ll be a man. Goro reflects on time passing, for the moment he’s a father but might be a grandad soon enough. The wheel keeps turning which perhaps puts the hire purchase fees on the TV he bought to keep Grandma occupied and out of the way into perspective. From the experimental opening to the occasional flashes of animation and that banana moon, Ichikawa paints a whimsical picture of the post-war world as seen through the eyes of a wise child but ironically finds a wealth of warmth and comfort even in an age of anxiety.

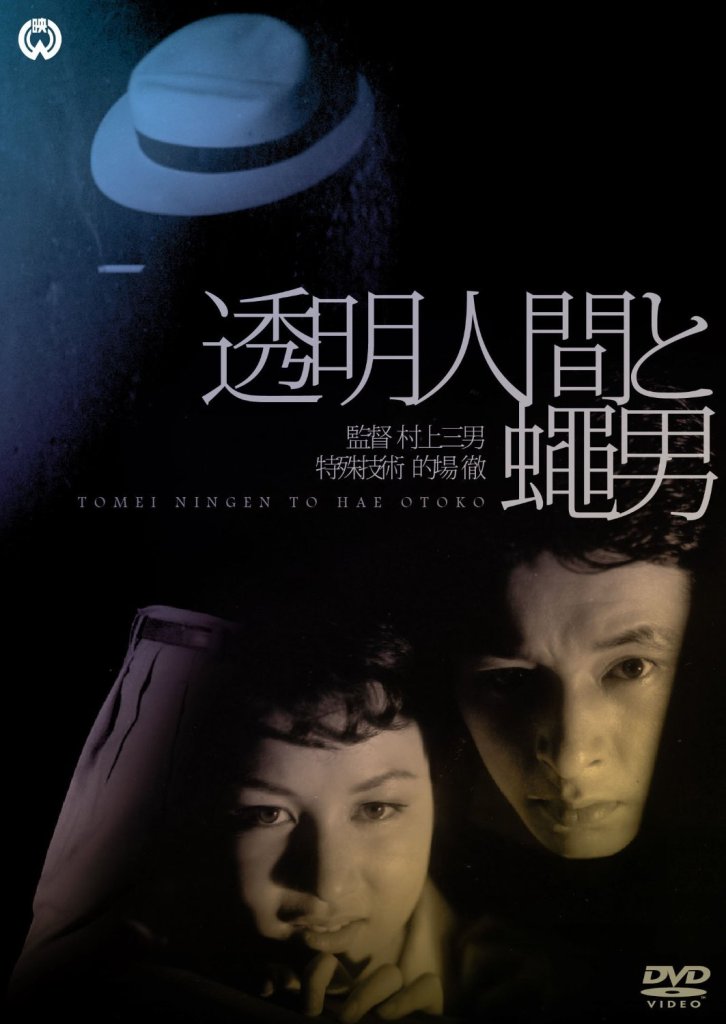

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on