Contemporary Japanese cinema has gone lukewarm on the idea of family, presenting it more often as a toxic rather than supporting presence. Among the few remaining positive voices, Ryota Nakano’s previous films Capturing Dad and Her Love Boils Bathwater never made any attempt to pretend that families are always perfect or that the family as a concept is one which must always be defended, but ultimately found warmth and solace in the mutual act of pulling together as the sometimes wounded protagonists found strength rather than suffocation in unconditional love.

A Long Goodbye (長いお別れ, Nagai Owakare) finds something much the same as three women are forced to deal in different ways with their relationships with austere father Shohei (Tsutomu Yamazaki), once an authoritarian head master but now suffering from dementia and rapidly losing the ability to read. The first signs of decline are felt in 2007, prompting mum Yoko (Chieko Matsubara) to ring both of her increasingly distant, almost middle-aged daughters, and invite them to their father’s 70th birthday party,

33-year-old Fumi (Yu Aoi) is in the middle of breaking up with a boyfriend who’s giving up on his dreams of being a novelist to take over the family potato farm. Fumi’s dream is owning her own restaurant, but somehow it seems a long way off. Older sister Mari (Yuko Takeuchi), meanwhile, is a housewife and mother living with her fish scientist husband Shin (Yukiya Kitamura) and son Takashi (Yuito Kamata) in California. Lonely in her marriage, Mari struggles with her English and finds it difficult to make friends with her husband’s colleagues who openly criticise her language skills from across the room while Shin makes no attempt to defend her.

Meanwhile, Yoko carries the heaviest burden alone in trying to manage her husband’s decline even as he begins to wander off, forever asking to go “home” even when he is already there. The concept of “home” however may be difficult to define in a rapidly changing society. All the way across the sea, Mari frets about her parents and feels guilty that, as the older sister, she should be doing more and has unfairly left everything to Fumi just because she happens to be in closer proximity. She is then slightly perturbed to realise that Fumi hasn’t seen their parents since the previous New Year and is equally shocked at the noticeable change in her father who goes off on random tangents and suddenly loses his temper over trivial things.

Mari flies back to Japan when crises occur but her husband is not as understanding as one might expect. His research concerns fish which adapt to their environment and it’s clear he’s begun to follow their example, falling wholesale for Western individualism. He criticises Mari’s anxiety for her parents’ health by reminding her that her “family” is her husband and son, bearing no responsibility for additional relatives. Shin now believes strongly in individual responsibility, that Shohei and Yoko need to look after themselves. As such he takes little interest in his family leaving all the childcare duties to Mari in somehow believing that children raise themselves. When the teenage Takashi (Rairu Sugita) goes off the rails and starts skipping school, Mari turns to the time old philosophy that he needs a good talking to from his father, but all Shin can come up with is that his son’s his own man and he’s sure he has his reasons.

The young Takashi is acclimatising too, getting himself a red-haired Californian girlfriend who’s obsessed with J-pop and kanji, but later replaces him with another Asian guy when he goes back to Japan to spend time with Shohei while he’s still somewhat present. Meanwhile, Fumi works hard to realise her dream but encounters a series of disappointments both romantic and professional as she too reconsiders the idea of family and whether it’s truly possible to slide into one that has already fractured. Becoming responsible for her parents’ care shifts her into a maternal role she might not have expected, maturing in a slightly different direction while Mari remains trapped and lonely, neglected by her newly individualist husband who only cares about his research and shut out by her understandably angsty teenage son.

Crises are, however, good for bringing people back together. Shohei it seems was a typical father of his times, distant and authoritarian, perhaps not always easy to be around. Fumi worries that she disappointed him, not becoming a teacher as he’d hoped while also failing to achieve her dreams of becoming a restaurateur, while Mari just wants what her parents had in a loving and supportive marriage surrounded by the warmth of family. Shohei might not always have shown it, but there’s a lot unsaid in his constant desire to go “home” back to the time his kids were small. Home is where the heart is after all, even if you don’t quite remember the way.

Original trailer (No subtitles)

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair.

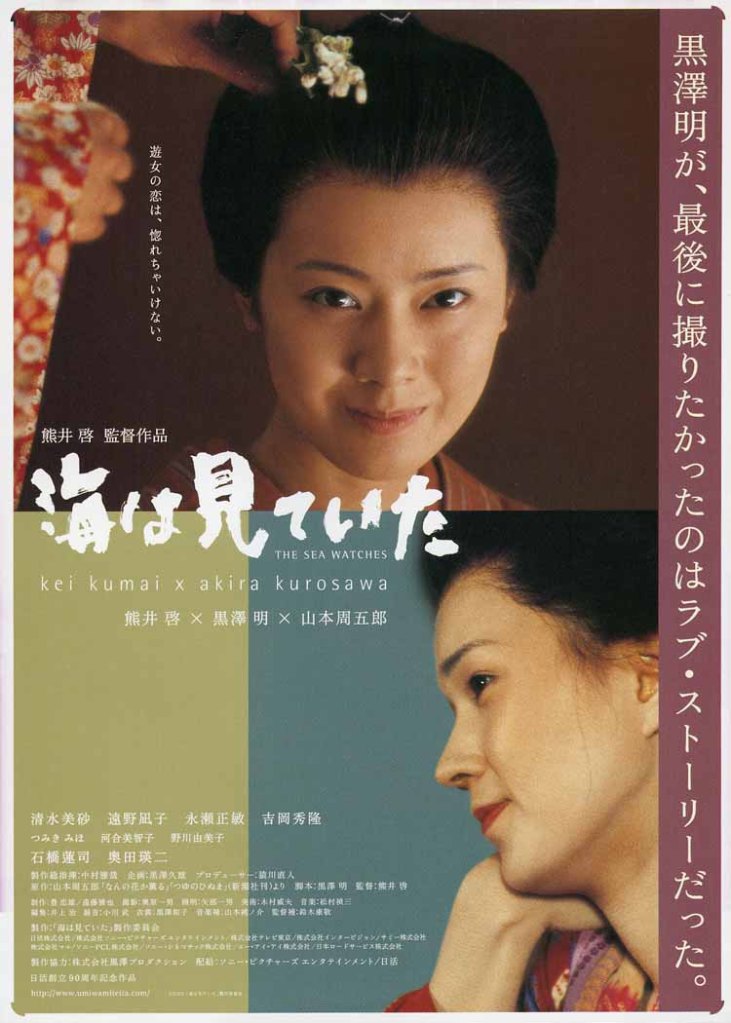

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair. Akira Kurosawa’s later career was marred by personal crises related to his inability to obtain the kind of recognition for his films he’d been used to in his heyday during the golden age of Japanese cinema. His greatest dream was to die on the set, but after suffering a nasty accident in 1995 he was no longer able to realise his ambition of directing again. However, shortly after he died, the idea was floated of filming some of the scripts Kurosawa had written but never proceed with to the production stage including The Sea is Watching (海は見ていた, Umi wa Miteita) which he wrote in 1993. Based on a couple of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto, The Sea is Watching would have been quite an interesting entry in Kurosawa’s back catalogue as it’s a rare female led story focussing on the lives of two geisha in Edo era Japan.

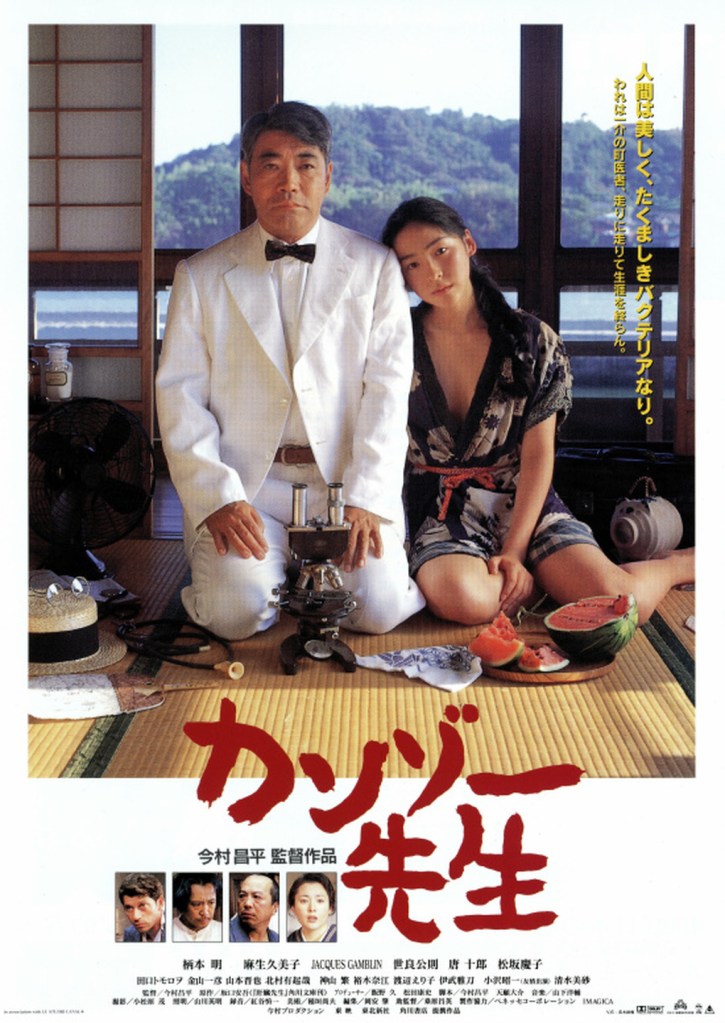

Akira Kurosawa’s later career was marred by personal crises related to his inability to obtain the kind of recognition for his films he’d been used to in his heyday during the golden age of Japanese cinema. His greatest dream was to die on the set, but after suffering a nasty accident in 1995 he was no longer able to realise his ambition of directing again. However, shortly after he died, the idea was floated of filming some of the scripts Kurosawa had written but never proceed with to the production stage including The Sea is Watching (海は見ていた, Umi wa Miteita) which he wrote in 1993. Based on a couple of short stories by Shugoro Yamamoto, The Sea is Watching would have been quite an interesting entry in Kurosawa’s back catalogue as it’s a rare female led story focussing on the lives of two geisha in Edo era Japan. A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II.

A late career entry from socially minded director Shohei Imamura, Dr. Akagi (カンゾー先生, Kanzo Sensei) takes him back to the war years but perhaps to a slightly more bourgeois milieu than his previous work had hitherto focussed on. Based on the book by Ango Sakaguchi, Dr. Akagi is the story of one ordinary “family doctor” in the dying days of World War II. The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go.

The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go.