Following the first previews around six weeks ago, the world’s biggest festival dedicated to Japanese cinema has now unveiled the full lineup for 2017! Taking place in Frankfurt from May 23 – 28, Nippon Connection is divided into six strands featuring everything from the latest blockbusters to retrospectives, animation, a children’s section and a selection of cultural events and lectures. There are around 100 films on offer and we’ll be previewing some of the strands separately over the next few days beginning with:

Following the first previews around six weeks ago, the world’s biggest festival dedicated to Japanese cinema has now unveiled the full lineup for 2017! Taking place in Frankfurt from May 23 – 28, Nippon Connection is divided into six strands featuring everything from the latest blockbusters to retrospectives, animation, a children’s section and a selection of cultural events and lectures. There are around 100 films on offer and we’ll be previewing some of the strands separately over the next few days beginning with:

Nippon Cinema

The Nippon Cinema section aims to showcase some of the biggest mainstream cinema hits of recent times with a few old favourites thrown in to boot. The Nippon Cinema award, bestowed by the festival’s audience, includes a prize of €2000 sponsored by Bankhaus Metzler.

Kenji Yamauchi adapts his own play At the Terrace – a tense yet farcical comedy of manners in which the artifice of propriety is gradually stripped away from a collection of wealthy party guests. Check out our review for a more detailed description.

Kenji Yamauchi adapts his own play At the Terrace – a tense yet farcical comedy of manners in which the artifice of propriety is gradually stripped away from a collection of wealthy party guests. Check out our review for a more detailed description.

Katsuya Tomita makes a welcome return following his critically acclaimed Saudade with a lengthy yet engrossing tale of love and the red light district as a Thai girl tries to make a life for herself in Bangkok’s Japan-centric hostess bars and brothels. Take a look at our review of Bangkok Nites from late last year for more information on this impressive, expansive film.

Katsuya Tomita makes a welcome return following his critically acclaimed Saudade with a lengthy yet engrossing tale of love and the red light district as a Thai girl tries to make a life for herself in Bangkok’s Japan-centric hostess bars and brothels. Take a look at our review of Bangkok Nites from late last year for more information on this impressive, expansive film.

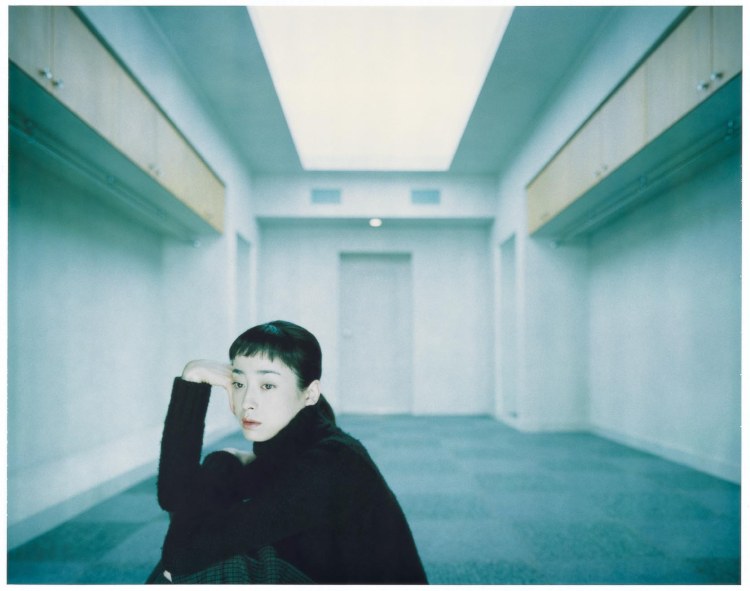

Shunji Iwai is another director making a welcome return with the equally epic A Bride for Rip Van Winkle. This quietly melancholy tale of a drifting shy girl gently nudged into a more positive place through a series of seeming crises is another beautifully drawn character study from Iwai who has been absent from cinema screens for far too long. Check out our review here.

Shunji Iwai is another director making a welcome return with the equally epic A Bride for Rip Van Winkle. This quietly melancholy tale of a drifting shy girl gently nudged into a more positive place through a series of seeming crises is another beautifully drawn character study from Iwai who has been absent from cinema screens for far too long. Check out our review here.

Daguerreotype is something of a departure from the other films on offer as it’s entirely in French. Starring one of France’s best young actors in Tahar Rahim, the film also marks the first production mounted outside of Asia for veteran director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Taking him back to his psychological horror roots, Daguerreotype is a creepy gothic ghost story inspired both by Edgar Allen Poe and his Japanese namesake, Edogawa Rampo.

Daguerreotype is something of a departure from the other films on offer as it’s entirely in French. Starring one of France’s best young actors in Tahar Rahim, the film also marks the first production mounted outside of Asia for veteran director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Taking him back to his psychological horror roots, Daguerreotype is a creepy gothic ghost story inspired both by Edgar Allen Poe and his Japanese namesake, Edogawa Rampo.

Dawn of the Felines is one of the films created for Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno reboot project which is also being celebrated with a Roman Porno retrospective (more on this later on). Directed by Devil’s Path director Kazuya Shiraishi, this melancholy tale of three girls working in Tokyo’s red light district takes its name from Noboru Tanaka’s classic pink film Night of the Felines.

Dawn of the Felines is one of the films created for Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno reboot project which is also being celebrated with a Roman Porno retrospective (more on this later on). Directed by Devil’s Path director Kazuya Shiraishi, this melancholy tale of three girls working in Tokyo’s red light district takes its name from Noboru Tanaka’s classic pink film Night of the Felines.

Directed by one of Japan’s foremost blockbuster helmers Shinsuke Sato (whose I am a Hero is also screening in the festival) Death Note: Light up The New World is the latest in a series of films inspired by Tsugumi Ohba’s manga in which a death god drops his precious ledger which has the power to kill anyone whose name is written inside it. Starring some of Japan’s best young actors in Masahiro Higashide, Sosuke Ikematsu, and Masaki Suda this latest installment promises exciting thrills with a philosophical edge.

Directed by one of Japan’s foremost blockbuster helmers Shinsuke Sato (whose I am a Hero is also screening in the festival) Death Note: Light up The New World is the latest in a series of films inspired by Tsugumi Ohba’s manga in which a death god drops his precious ledger which has the power to kill anyone whose name is written inside it. Starring some of Japan’s best young actors in Masahiro Higashide, Sosuke Ikematsu, and Masaki Suda this latest installment promises exciting thrills with a philosophical edge.

If Death Note wasn’t nihilistic enough for you, the festival will also feature Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies. This hard-hitting tale of violent youth and hopeless futures again stars some of Japan’s best younger actors in Yuya Yagira, Masaki Suda, Nana Komatsu and Sosuke Ikematsu. Director Tetsuya Mariko is also expected to attend the festival in person to present the film. Review.

If Death Note wasn’t nihilistic enough for you, the festival will also feature Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies. This hard-hitting tale of violent youth and hopeless futures again stars some of Japan’s best younger actors in Yuya Yagira, Masaki Suda, Nana Komatsu and Sosuke Ikematsu. Director Tetsuya Mariko is also expected to attend the festival in person to present the film. Review.

Moving back in time a little, 2015’s The Emperor in August is Masato Harada’s attempt to chronicle the last days of the war as Japan reconciles itself to surrender and considers the best way to do it. The film stars veteran actor Koji Yakusho who will also be receiving the festival’s Nippon Honour Award in celebration of his long and successful career.

Moving back in time a little, 2015’s The Emperor in August is Masato Harada’s attempt to chronicle the last days of the war as Japan reconciles itself to surrender and considers the best way to do it. The film stars veteran actor Koji Yakusho who will also be receiving the festival’s Nippon Honour Award in celebration of his long and successful career.

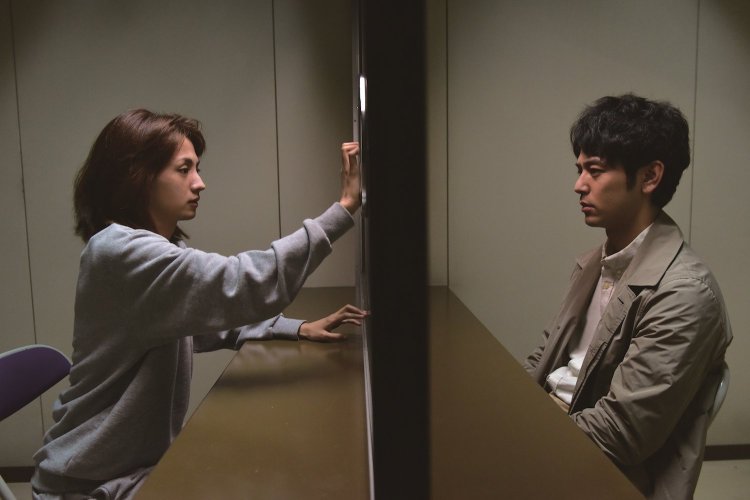

The debut film from Kei Ishikawa, Gukoroku: Traces of Sin stars Satoshi Tsumabuki as an ambitious reporter trying to find the truth behind the brutal, unsolved murder of an ordinary Tokyo family.

The debut film from Kei Ishikawa, Gukoroku: Traces of Sin stars Satoshi Tsumabuki as an ambitious reporter trying to find the truth behind the brutal, unsolved murder of an ordinary Tokyo family.

In the first of two films presented at the festival, SABU goes on an existential journey in Happiness as a mysterious man appears in town with a strange helmet which allows the wearer to re-experience the happiest moment of their lives. Stars veteran actor Masatoshi Nagase.

In the first of two films presented at the festival, SABU goes on an existential journey in Happiness as a mysterious man appears in town with a strange helmet which allows the wearer to re-experience the happiest moment of their lives. Stars veteran actor Masatoshi Nagase.

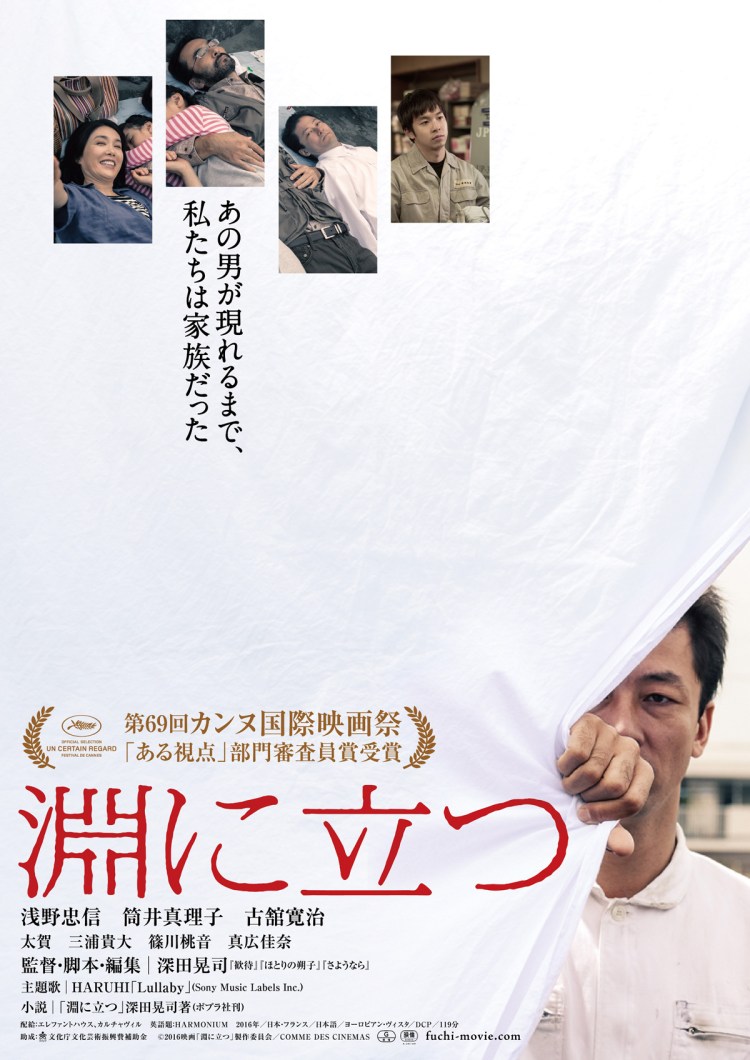

Koji Fukada returns to the themes of family and disruptive interlopers but skews darker than ever before in Harmonium. Tadanobu Asano stars as the home invader recently released from prison and taking refuge with “an old friend” but there’s something decidedly strange about his relationship with the father of the family and generally ominous presence. You can check our review of the film from late last year here.

Koji Fukada returns to the themes of family and disruptive interlopers but skews darker than ever before in Harmonium. Tadanobu Asano stars as the home invader recently released from prison and taking refuge with “an old friend” but there’s something decidedly strange about his relationship with the father of the family and generally ominous presence. You can check our review of the film from late last year here.

Her Love Boils Bathwater officially opens the festival and stars Rie Miyazawa as a single mother diagnosed with a terminal illness who is determined to bring her disparate family back together and save the family bathhouse in the process. Rie Miyazawa picked up the best actress award at this year’s Japan Academy Prize ceremony for her role in film which is far funnier than its synopsis sounds.

Her Love Boils Bathwater officially opens the festival and stars Rie Miyazawa as a single mother diagnosed with a terminal illness who is determined to bring her disparate family back together and save the family bathhouse in the process. Rie Miyazawa picked up the best actress award at this year’s Japan Academy Prize ceremony for her role in film which is far funnier than its synopsis sounds.

From one hero to another, the second movie helmed by director Shinsuke Sato to feature in the festival stars comedian Yo Oizumi as a mildmannered, unsuccessful mangaka who finds hidden reserves inside himself when faced with the zombie apocalypse. I am a Hero is adapted from the manga by Kengo Hanazawa and you can check out our review of the film here.

From one hero to another, the second movie helmed by director Shinsuke Sato to feature in the festival stars comedian Yo Oizumi as a mildmannered, unsuccessful mangaka who finds hidden reserves inside himself when faced with the zombie apocalypse. I am a Hero is adapted from the manga by Kengo Hanazawa and you can check out our review of the film here.

From one plucky underdog to another – Let’s Go Jets! From Small Town Girls to U.S. Champions?! stars a team of aspiring Japanese cheerleaders who want to strut their stuff all the way to the top spot in the US championships.

From one plucky underdog to another – Let’s Go Jets! From Small Town Girls to U.S. Champions?! stars a team of aspiring Japanese cheerleaders who want to strut their stuff all the way to the top spot in the US championships.

Miwa Nishikawa returns with The Long Excuse – an adaptation of her own novel starring Masahiro Motoki as a self centered author and minor celebrity who is unmoved when his wife dies in a bus accident but finds his humanity reawakening after bonding with the bereaved children of the best friend who died beside her.

Miwa Nishikawa returns with The Long Excuse – an adaptation of her own novel starring Masahiro Motoki as a self centered author and minor celebrity who is unmoved when his wife dies in a bus accident but finds his humanity reawakening after bonding with the bereaved children of the best friend who died beside her.

SABU’s second film in the festival, Mr. Long, sees a hardened Taiwanese hitman taken in by a kindly little boy and his family after a job goes badly wrong.

SABU’s second film in the festival, Mr. Long, sees a hardened Taiwanese hitman taken in by a kindly little boy and his family after a job goes badly wrong.

Nobuhiro Yamashita is another director with not one but two films making it into the festival this year. The first of them, My Uncle, is a hilarious tale of an exasperated nephew’s eventual bonding with his father’s younger brother – a part time professor of philosophy who has an answer for everything but spends most of his time lying on his futon “thinking” or “resting his brain” by reading children’s manga. Check out our review here.

Nobuhiro Yamashita is another director with not one but two films making it into the festival this year. The first of them, My Uncle, is a hilarious tale of an exasperated nephew’s eventual bonding with his father’s younger brother – a part time professor of philosophy who has an answer for everything but spends most of his time lying on his futon “thinking” or “resting his brain” by reading children’s manga. Check out our review here.

Yamashita’s second entry, Over the Fence, is a slightly less cheerful affair. Joe Odagiri stars as a recently divorced man returing to his hometown of Hakodate who eventually learns to open himself up to new possibilities through an intense relationship with zookeeper/hostess Yu Aoi whose emotional volatility neatly counters his internal numbness. Review here.

Yamashita’s second entry, Over the Fence, is a slightly less cheerful affair. Joe Odagiri stars as a recently divorced man returing to his hometown of Hakodate who eventually learns to open himself up to new possibilities through an intense relationship with zookeeper/hostess Yu Aoi whose emotional volatility neatly counters his internal numbness. Review here.

Rumour and speculation dominate a housing estate when one half of a recently arrived older couple abruptly disappears. Moonlight flit? Murder? Divorce, affairs, scandal? The truth is stranger than fiction in Junji Sakamoto’s absurd comedy The Projects.

Rumour and speculation dominate a housing estate when one half of a recently arrived older couple abruptly disappears. Moonlight flit? Murder? Divorce, affairs, scandal? The truth is stranger than fiction in Junji Sakamoto’s absurd comedy The Projects.

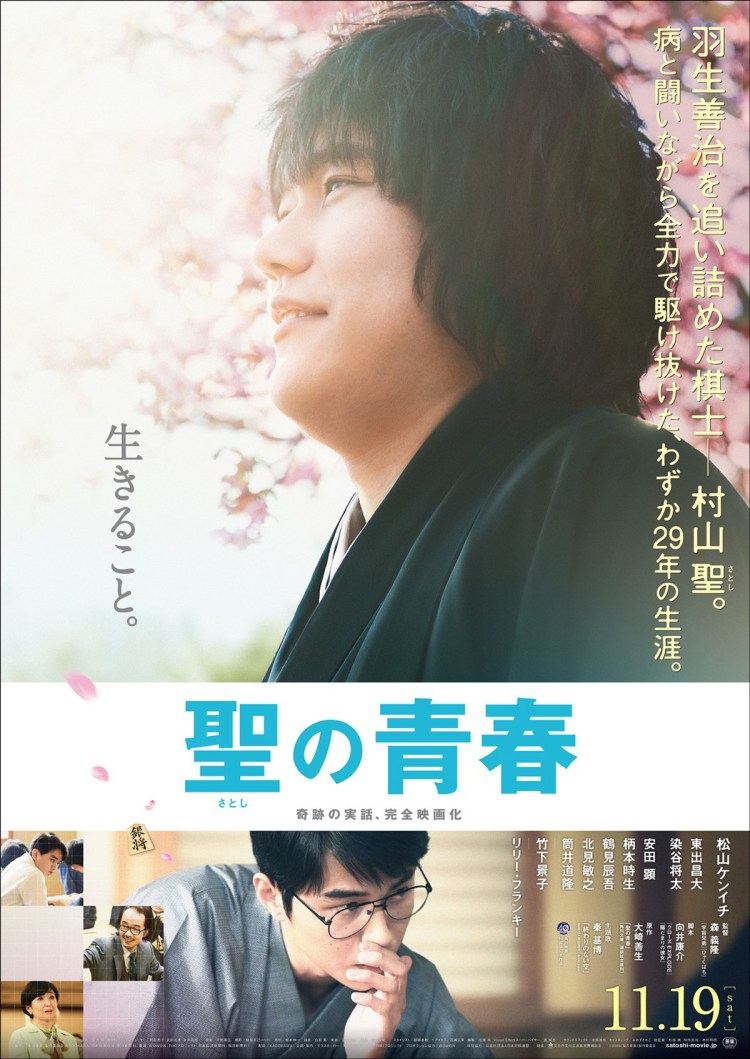

Satoshi: A Move for Tomorrow is the true life story of tragic shogi player Satoshi Murayama who first developed a love of the game during a childhood illness and subsequently devoted his entire life to its mastery despite his declining health. Review.

Satoshi: A Move for Tomorrow is the true life story of tragic shogi player Satoshi Murayama who first developed a love of the game during a childhood illness and subsequently devoted his entire life to its mastery despite his declining health. Review.

Godzilla is back and bigger than ever! Directed by Evangelion’s Hideaki Anno along with live action Attack on Titan director Shinji Higuchi Shin Godzilla (Godzilla Resurgence) is equal parts classic monster movie and biting political satire.

Godzilla is back and bigger than ever! Directed by Evangelion’s Hideaki Anno along with live action Attack on Titan director Shinji Higuchi Shin Godzilla (Godzilla Resurgence) is equal parts classic monster movie and biting political satire.

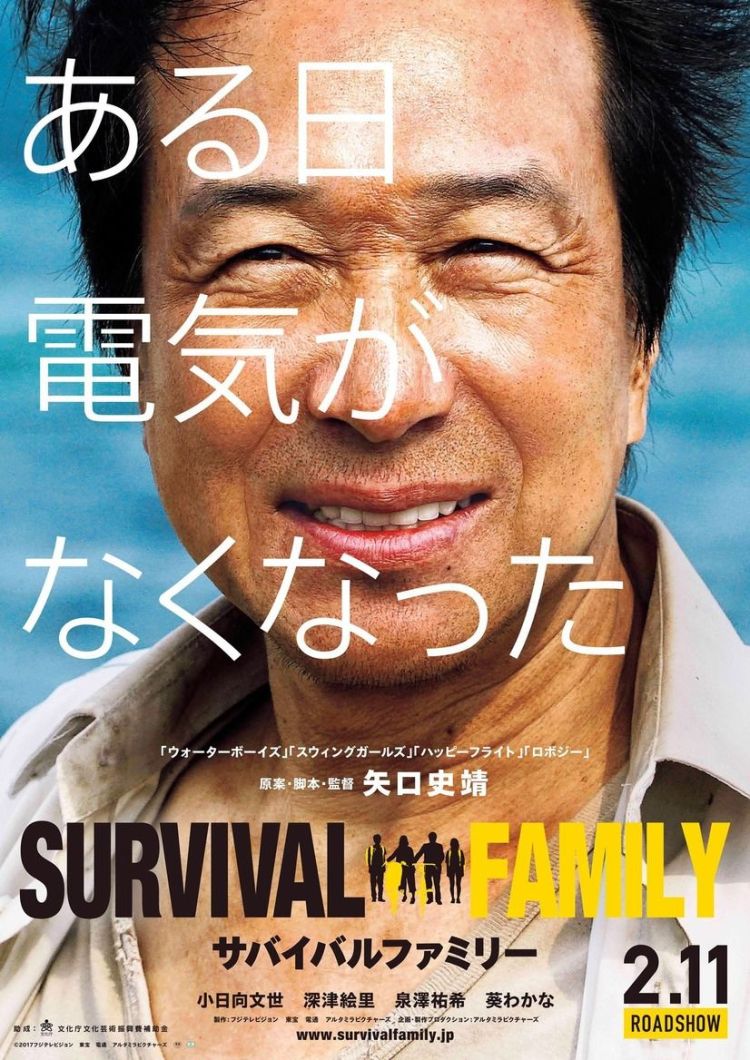

Godzilla’s not the only existential threat posed to Japanese society as one ordinary family find out in Shinobu Yaguchi’s black out drama. Survival Family begins with the unthinkable as a simple power outage lasts for days with no official explanation. After waiting patiently for the problem to be resolved, the Suzuki family decide to escape the city to find Mrs. Suzuki’s survivalist father in the hope that he will know how to cope with the post-electric world. Review.

Godzilla’s not the only existential threat posed to Japanese society as one ordinary family find out in Shinobu Yaguchi’s black out drama. Survival Family begins with the unthinkable as a simple power outage lasts for days with no official explanation. After waiting patiently for the problem to be resolved, the Suzuki family decide to escape the city to find Mrs. Suzuki’s survivalist father in the hope that he will know how to cope with the post-electric world. Review.

Now for something completely different – Juzo Itami’s noodle western Tampopo will also screen as a Nippon Film Dinner during which bento boxes filled with delicious Japanese treats will be served.

Now for something completely different – Juzo Itami’s noodle western Tampopo will also screen as a Nippon Film Dinner during which bento boxes filled with delicious Japanese treats will be served.

After dinner comes breakfast! This one is screening with German subtitles only but if you can understand German or Japanese or don’t mind not understanding anything at all you can enjoy a delicious breakfast buffet whilst taking in Jun Ichikawa’s adaptation of the Haruki Murakami short story Tony Takitani in which a lonely man meets and falls in love with a beautiful woman only for her obsession with shopping to come between them.

After dinner comes breakfast! This one is screening with German subtitles only but if you can understand German or Japanese or don’t mind not understanding anything at all you can enjoy a delicious breakfast buffet whilst taking in Jun Ichikawa’s adaptation of the Haruki Murakami short story Tony Takitani in which a lonely man meets and falls in love with a beautiful woman only for her obsession with shopping to come between them.

Finally, Akihiko Shiota’s Wet Woman in the Wind is the second of the Roman Porno Reboot movies to be featured in the festival and follows the adventures of a playwright with writer’s block who tries to retreat to the country for some peace, quiet, and time to reflect. Then he hooks up with a nymphomaniac waitress instead!

Finally, Akihiko Shiota’s Wet Woman in the Wind is the second of the Roman Porno Reboot movies to be featured in the festival and follows the adventures of a playwright with writer’s block who tries to retreat to the country for some peace, quiet, and time to reflect. Then he hooks up with a nymphomaniac waitress instead!

That’s all for Nippon Cinema – join us again next time for a look at Nippon Visions, a strand dedicated to bold new innovations and special formats. You can find the full details for all the films, screening times and ticket links on the festival’s official website and you can also keep up with all the latest news via the Nippon Connection Facebook Page, Twitter account, and Instagram channel.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper.

There’s a slight irony in the English title of Yoshitaka Mori’s tragic shogi star biopic, Satoshi: A Move For Tomorrow (聖の青春, Satoshi no Seishun). The Japanese title does something similar with the simple “Satoshi’s Youth” but both undercut the fact that Satoshi (Kenichi Matsuyama) was a man who only ever had his youth and knew there was no future for him to consider. The fact that he devoted his short life to a game that’s all about thinking ahead is another wry irony but one it seems the man himself may have enjoyed. Satoshi Murayama, a household name in Japan, died at only 29 years old after denying chemotherapy treatment for bladder cancer in fear that it would interfere with his thought process and set him back on his quest to conquer the world of shogi. Less a story of triumph over adversity than of noble perseverance, Satoshi lacks the classic underdog beats the odds narrative so central to the sports drama but never quite manages to replace it with something deeper. Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Every keen dramatist knows the most exciting things which happen at a party are always those which occur away from the main action. Lonely cigarette breaks and kitchen conversations give rise to the most unexpected of events as those desperately trying to escape the party atmosphere accidentally let their guard down in their sudden relief. Adapting his own stage play titled Trois Grotesque, Kenji Yamauchi takes this idea to its natural conclusion in At the Terrace (テラスにて, Terrace Nite) setting the entirety of the action on the rear terraced area of an elegant European-style villa shortly after the majority of guests have departed following a business themed dinner party. This farcical comedy of manners neatly sends up the various layers of propriety and the difficulty of maintaining strict social codes amongst a group of intimate strangers, lending a Japanese twist to a well honed European tradition.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair. Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.

Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world. Nippon Connection is the largest festival dedicated to Japanese Cinema anywhere in the world and returns in 2017 for its 17th edition. Once again taking place in Frankfurt, the festival will screen over 100 films from May 23 – 28, many of which will also welcome members of the creative team eager to present to their work to an appreciative audience.

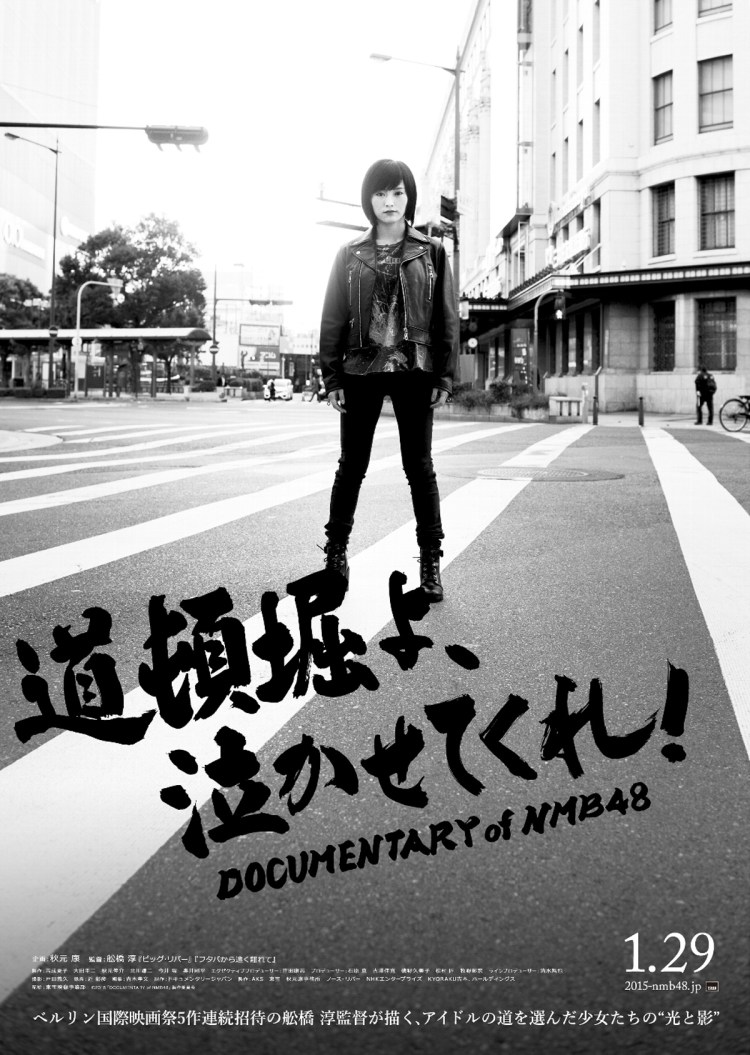

Nippon Connection is the largest festival dedicated to Japanese Cinema anywhere in the world and returns in 2017 for its 17th edition. Once again taking place in Frankfurt, the festival will screen over 100 films from May 23 – 28, many of which will also welcome members of the creative team eager to present to their work to an appreciative audience. Director Atsushi Funahashi has hitherto been known for hard hitting fare such as the Fukushima documentary Nuclear Nation as well as narrative films including the heartrending Cold Bloom and cross cultural odyssey Big River. Consequently he steps into the slowly growing genre of idol documentaries from the refreshing position of a total novice. Adopting an objective viewpoint, Funahashi rigourously dissects this complicated phenomenon whilst taking care never to misrepresent the girls, their dreams, or their devoted fanbase.

Director Atsushi Funahashi has hitherto been known for hard hitting fare such as the Fukushima documentary Nuclear Nation as well as narrative films including the heartrending Cold Bloom and cross cultural odyssey Big River. Consequently he steps into the slowly growing genre of idol documentaries from the refreshing position of a total novice. Adopting an objective viewpoint, Funahashi rigourously dissects this complicated phenomenon whilst taking care never to misrepresent the girls, their dreams, or their devoted fanbase. Shot over six years, 95 and 6 to Go begins with a stalled fim project and some unexpected grandfatherly advice but eventually develops into a moving meditation on life, love, loss, and endurance.

Shot over six years, 95 and 6 to Go begins with a stalled fim project and some unexpected grandfatherly advice but eventually develops into a moving meditation on life, love, loss, and endurance. Previously screened at the BFI London Film Festival, Steven Okazaki’s documentary Mifune: The Last Samurai focuses firmly on Mifune’s place within the history of samurai cinema through exploring not only his life but also the early history of “chanbara” movies and the genre’s later echoes in American cinema as related by talking heads including Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese.

Previously screened at the BFI London Film Festival, Steven Okazaki’s documentary Mifune: The Last Samurai focuses firmly on Mifune’s place within the history of samurai cinema through exploring not only his life but also the early history of “chanbara” movies and the genre’s later echoes in American cinema as related by talking heads including Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese. Back in 2012, Kiyoshi Kurosawa planned his first international movie, 1905, which would have featured 90% Chinese dialogue and was set to shoot in Taiwan with stars Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Shota Matsuda and Atsuko Maeda. Sadly, political concerns of the day put paid to 1905, and so Daguerrotype marks Kurosawa’s first foray into non-Japanese language cinema. Starring one of France’s most interesting young actors in Tahar Rahim, this French language gothic ghost story takes the director back to his eerie days of psychological horror.

Back in 2012, Kiyoshi Kurosawa planned his first international movie, 1905, which would have featured 90% Chinese dialogue and was set to shoot in Taiwan with stars Tony Leung Chiu-Wai, Shota Matsuda and Atsuko Maeda. Sadly, political concerns of the day put paid to 1905, and so Daguerrotype marks Kurosawa’s first foray into non-Japanese language cinema. Starring one of France’s most interesting young actors in Tahar Rahim, this French language gothic ghost story takes the director back to his eerie days of psychological horror.

Masahiro Motoki makes a welcome return to leading man status as a self-centered B-list celebrity and former author who finds himself largely unmoved after his wife is killed in an accident but later bonds with the bereaved children of her best friend who died alongside her.

Masahiro Motoki makes a welcome return to leading man status as a self-centered B-list celebrity and former author who finds himself largely unmoved after his wife is killed in an accident but later bonds with the bereaved children of her best friend who died alongside her. You can check out our

You can check out our  Beyond nihilism, Destruction Babies paints a bleak prognosis for the youth of Japan who live without hope, disconnected from reality, and know only the sensation of violence. You can check out our review of the film

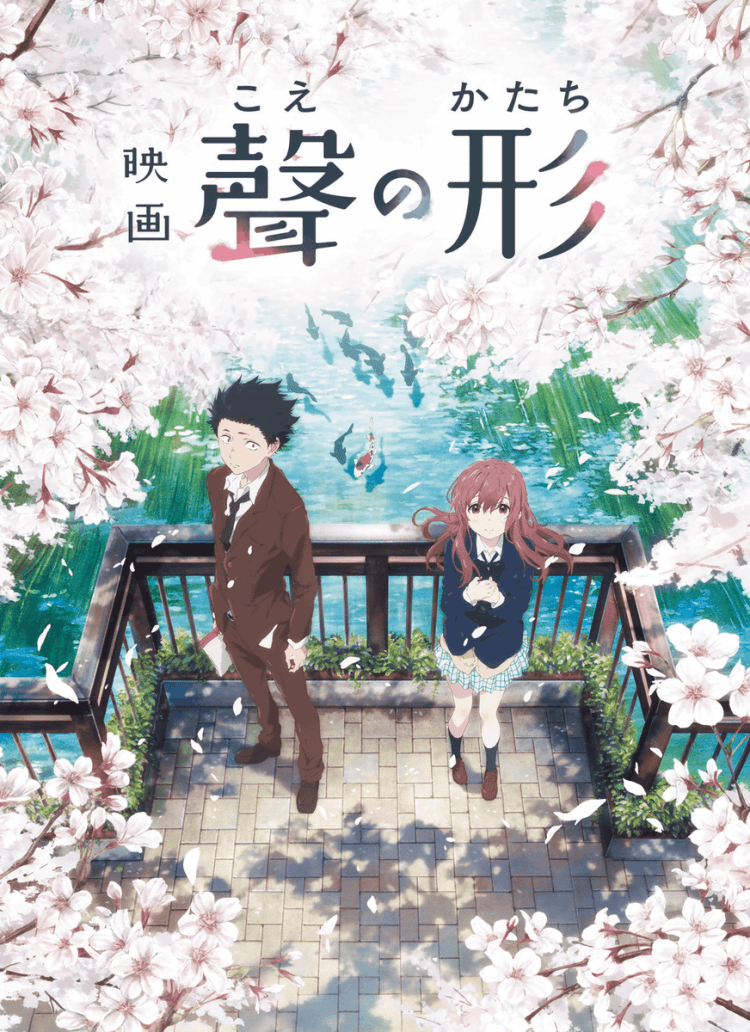

Beyond nihilism, Destruction Babies paints a bleak prognosis for the youth of Japan who live without hope, disconnected from reality, and know only the sensation of violence. You can check out our review of the film  Distributed in the UK by Anime Limited, this alternately heartrending and heartwarming drama examines the effects of social stigma, disibility, and the legacy of cruelty as its perfectly matched central pair confront the ghosts of their respective pasts and futures. You can check out our review from the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme over

Distributed in the UK by Anime Limited, this alternately heartrending and heartwarming drama examines the effects of social stigma, disibility, and the legacy of cruelty as its perfectly matched central pair confront the ghosts of their respective pasts and futures. You can check out our review from the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme over  From the director of Twisted Justice and Devil’s Path, Dawn of the Felines follows the adventures of three prostitutes in Tokyo’s red light district.

From the director of Twisted Justice and Devil’s Path, Dawn of the Felines follows the adventures of three prostitutes in Tokyo’s red light district. Shiota’s film follows a former playwright who tries to get out of town for some peace and quiet but runs into a nymphomaniac waitress instead. Oh well, a change is as good as a rest?

Shiota’s film follows a former playwright who tries to get out of town for some peace and quiet but runs into a nymphomaniac waitress instead. Oh well, a change is as good as a rest?

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness. Post-golden age, Japanese cinema has arguably had a preoccupation with the angry young man. From the ever present tension of the seishun eiga to the frustrations of ‘70s art films and the punk nihilism of the 1980s which only seemed to deepen after the bubble burst, the young men of Japanese cinema have most often gone to war with themselves in violent intensity, prepared to burn the world which they feel holds no place for them. Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies (ディストラクション・ベイビーズ) is a fine addition to this tradition but also an urgent one. Stepping somehow beyond nihilism, Mariko’s vision of his country’s future is a bleak one in which young, fatherless men inherit the traditions of their ancestors all the while desperately trying to destroy them. Devoid of hope, of purpose, and of human connection the youth of the day get their kicks vicariously, so busy sharing their experiences online that reality has become an obsolete concept and the physical sensation of violence the only remaining truth.

Post-golden age, Japanese cinema has arguably had a preoccupation with the angry young man. From the ever present tension of the seishun eiga to the frustrations of ‘70s art films and the punk nihilism of the 1980s which only seemed to deepen after the bubble burst, the young men of Japanese cinema have most often gone to war with themselves in violent intensity, prepared to burn the world which they feel holds no place for them. Tetsuya Mariko’s Destruction Babies (ディストラクション・ベイビーズ) is a fine addition to this tradition but also an urgent one. Stepping somehow beyond nihilism, Mariko’s vision of his country’s future is a bleak one in which young, fatherless men inherit the traditions of their ancestors all the while desperately trying to destroy them. Devoid of hope, of purpose, and of human connection the youth of the day get their kicks vicariously, so busy sharing their experiences online that reality has become an obsolete concept and the physical sensation of violence the only remaining truth.

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective.

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective.