Love can make you do funny things. It can also blind you to the world’s realities and colour the way you interpret the actions of others. At least, that’s how it is for the protagonists of Mai Sakai’s Cha-cha (チャチャ) who are all suffering with unrequited love and unbeknownst to them quite mistaken in their assumptions about the loves of others while otherwise solipsistically trapped in a bubble of frustrated romance.

Sometime narrator Rin (Sawako Fujima) is resentful of colleague Cha-Cha (Marika Ito) who is, ironically, the the total opposite of herself in that she’s free spirited and eccentric each qualities she assumes attract the opposite sex which Rin fears she herself does not. Chiefly she resents her because she has an unrequited crush on the boss, Kato, who is married with children though the interoffice gossip incorrectly suggests Cha-cha only got her job because she’s sleeping with him. According to Cha-cha, she is quite popular with men though describes herself as not being conventionally attractive and thinks men’s interest in her is usually more to do with conquest than romance. She develops a small crush on a handsome chef, Raku (Taishi Nakagawa), who smokes on their rooftop but though she ends up moving into his ramshackle home he does not appear to be interested in her and may in fact be suffering unrequited love for someone else.

Because of all of these emotions can be awkward or embarrassing, no one really talks about them openly which obviously gives rise to a series of misunderstandings about the feelings and actions of others. Jealous of Cha-Cha, Rin ends up stalking her to find out if she really is sleeping with the boss though as she herself is not willing to be an adulteress it seems like something of a moot point. Cha-Cha likes the chef precisely because they have nothing in common and are in fact total opposites, much as she’s also the total opposite of Rin. She likes the idea that they could lead complementary existences because while she hates melon but likes cucumber, he likes cucumber and hates melon.

She is also possibly drawn to him because they share a certain kind of darkness, admitting that she has a desire to lick the blood of the person she’s dating while he has a secret stash of lenses saved from the animal heads they sometimes get at the restaurant. Ironically, this shared quality may signal doom for their romance or ultimately force them together in a mutual act of settling for second best when their ideal romantic plans are disrupted by an unexpectedly extreme series of events. The most ironic thing is that the only genuine romance where feelings seem to be mutually returned, if imperfectly and with hints of exploitation, is doubted by others and motivates its own series of misapprehensions and petty jealousies.

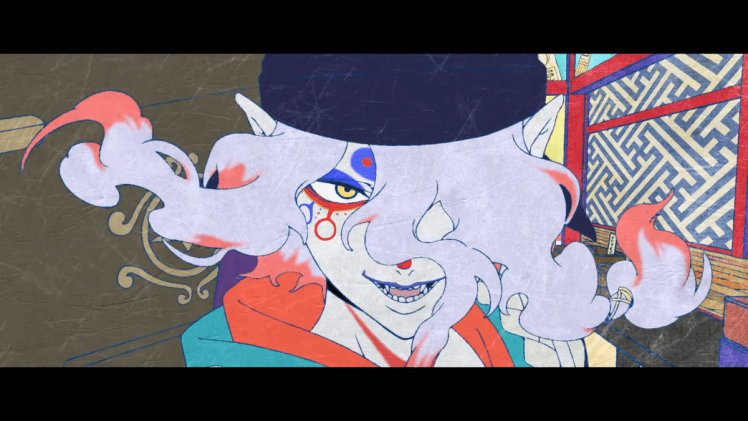

The strange events are at times narrated by a utility pole and telephone box who alone stand sturdy amid the changing and emotionally confusing environment of the present society. They are amused by the bizarre goings on among humans who seem incapable of being clear or honest in their romantic desires and often entirely misread the body language and behaviour of those around them to suit their own narrative. Rin thinks Cha-Cha probably is sleeping with the boss because they ignore each other, while a co-worker who admires her thinks she dislikes the boss because she avoids looking at him and assumes she likes another colleague, Aoki, ironically because she looks at him without bashfulness.

It’s all par for the course in cha cha cha of love, and despite the dark turn the narrative may eventually take Sakai maintains an air of absurdist normality aided by quirky production design and a sense of wonder for a world that remains remains strange and difficult to understand, the protagonists individually blinkered views not withstanding. In any case, Rin’s eventual acceptance of Cha-Cha leads her to a desire to live “a more impulsive life” that will probably never be fulfilled but in some ways perhaps love is better as an unrequited fantasy than compromised reality if only it did not become an all encompassing obsession. As an imperfect man cheerfully in love tells her, perhaps Cha-Cha should focus on how to make herself happy rather than chasing an illusionary dream of love though in the end perhaps it’s all the same anyway.

Cha-Cha screened as part of this year’s JAPAN CUTS.

Trailer (English subtitles)