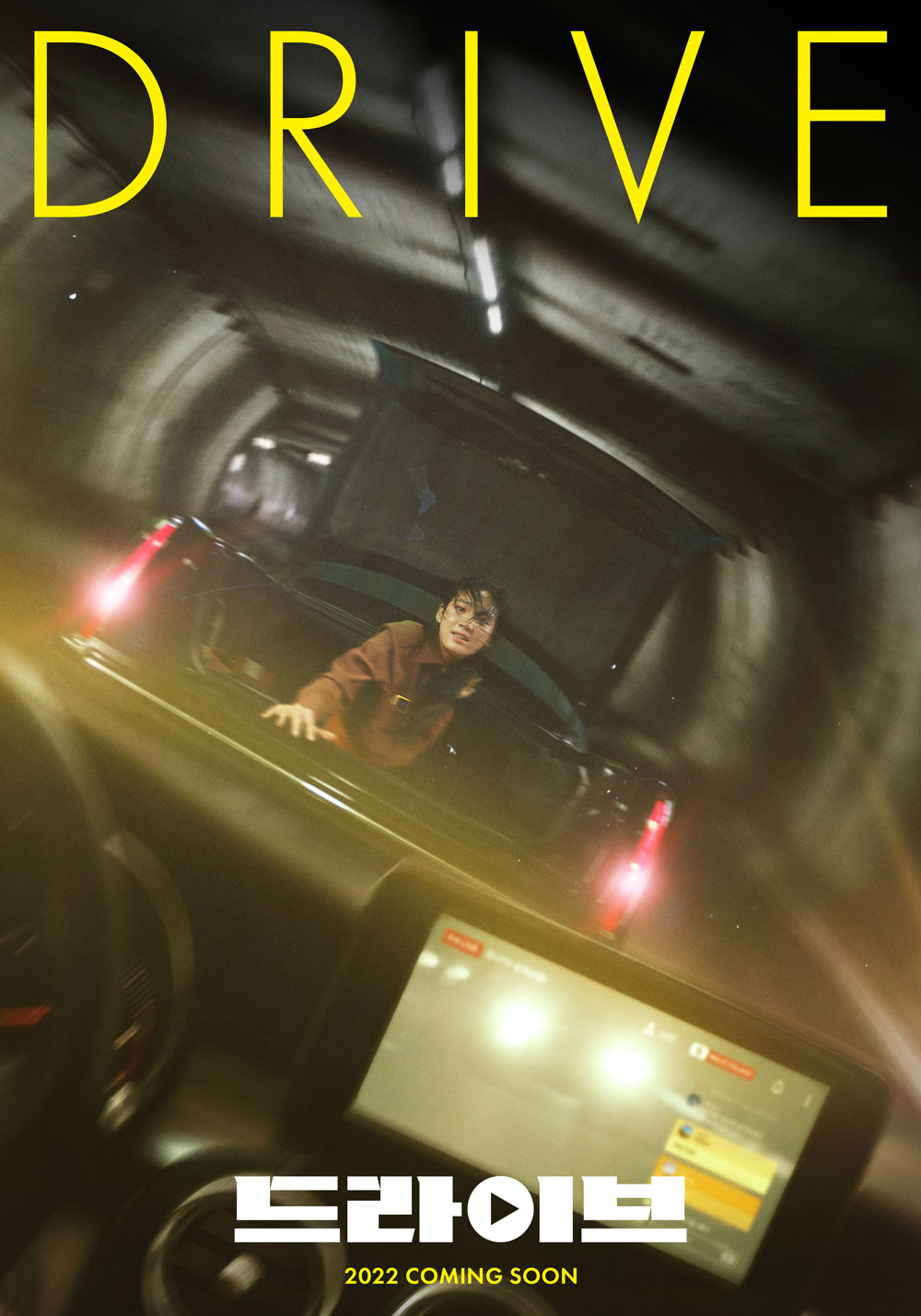

“Be sincere if you want other people’s money” an influencer is told during a contract negotiation, but as she’s forced to admit in Park Dong-hee’s tense kidnap thriller Drive (드라이브) her whole world is hollow. Even so, sincerity was it seems something people wanted from her and tragically did not get, though for others what undoubtedly sells is a fantasy life of “easy” money and total independence free from an oppressive work culture if not quite from the patriarchal society.

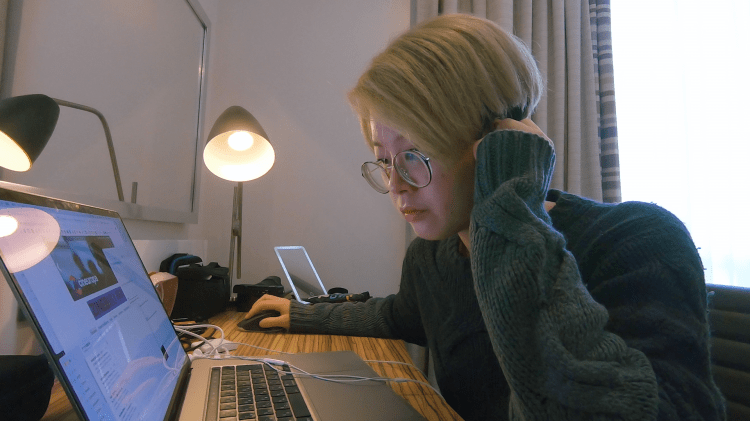

An opening sequence charts the gradual evolution of Yuna (Park Ju-Hyun) from shy young woman venturing into streaming to rising star of the online world. As someone points out she’s good at negotiating though is prepared to screw over even those closest to her in the hope of advancement while indulging in underhanded tactics such as encouraging companies to break contracts with other streamers with the promise of covering their damages. She’s also secretly plotting to throw over her long time manager and join a large media conglomerate even if, as it turns out, the boss is about to make her an indecent proposal.

Yet the truth she’s confronted with after being kidnapped is that none of it’s quite real. She doesn’t actually have vast wealth, nothing really belongs to her but is merely on loan to use as endorsements. Stuffing her in the boot of her own car, the kidnapper asks for a million won which Yuna can’t pay leading them to force her to livestream her own kidnapping and hopefully earn the remainder of the money from her adoring fans. The problem is that no one really believes she has actually been kidnapped. Everyone assumes it’s a publicity stunt while the kidnapper tells her if she doesn’t get the money she’ll be driven into a scrapyard and never seen again.

Now dependent on her “fans” whom she had previously described as “creeps”, Yuna is repeatedly told to reveal her real self. The boot of the car becomes a kind of purgatorial space, Yuna later coming to the realisation that the reason she’s not been able to escape is that she has not yet succeeded embracing herself as she is. Her YouTube persona is constructed as much for herself as others, to protect herself from unpleasantness or the stigma of being unsuccessful. She invents a life for herself as the daughter of a businessman who took his own life after his business failed, but prides herself on being a good businesswoman even if that means some underhanded tactics but then she’s not the only one playing dirty in the influencer game.

Yuna certainly has a “drive” to succeed, but the paradox lies in the enigma of the degree to which people, including herself, expect or deflect sincerity. Some obviously crave it, desperate to believe that Yuna really is their friend who cares for them deeply while others want the exact opposite, a hollow figure onto which they can project their image of contemporary success and fantasy of living the high life. It seems that success has made Yuna less forgiving, adopting a haughty attitude and frequently dismissing those around her. If she wants to get out of the boot, she’s going to have to face her authentic self finally looking at her own reflection in the blank screen of a tablet long after the stream has ended.

The kidnapper challenges her to debase herself, asking how far she’ll go to save her life but equally if her “fans” are willing to pay to save her while other streamers later get in on the action too, mainly getting in the way and willing to endanger Yuna’s survival for their own livelihood. In someways exposing the hollow artifice of influencer culture, the film eventually pulls back to ask if it isn’t a frustrated desire for connection fuelled by those who long to be seen and are in effect attempting to fill an emotional void with the quantifiable love of an online following. At the peak of her success, Yuna realises her time may be ending as young stars creep up behind her and she has to run to stay in the game but in the end can no longer run from herself or the hollowness of her life whether she really does end up on the scrap heap of contemporary culture or not.

Drive screens in Chicago Oct.7 as part of the 17th season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema

International trailer (English subtitles)