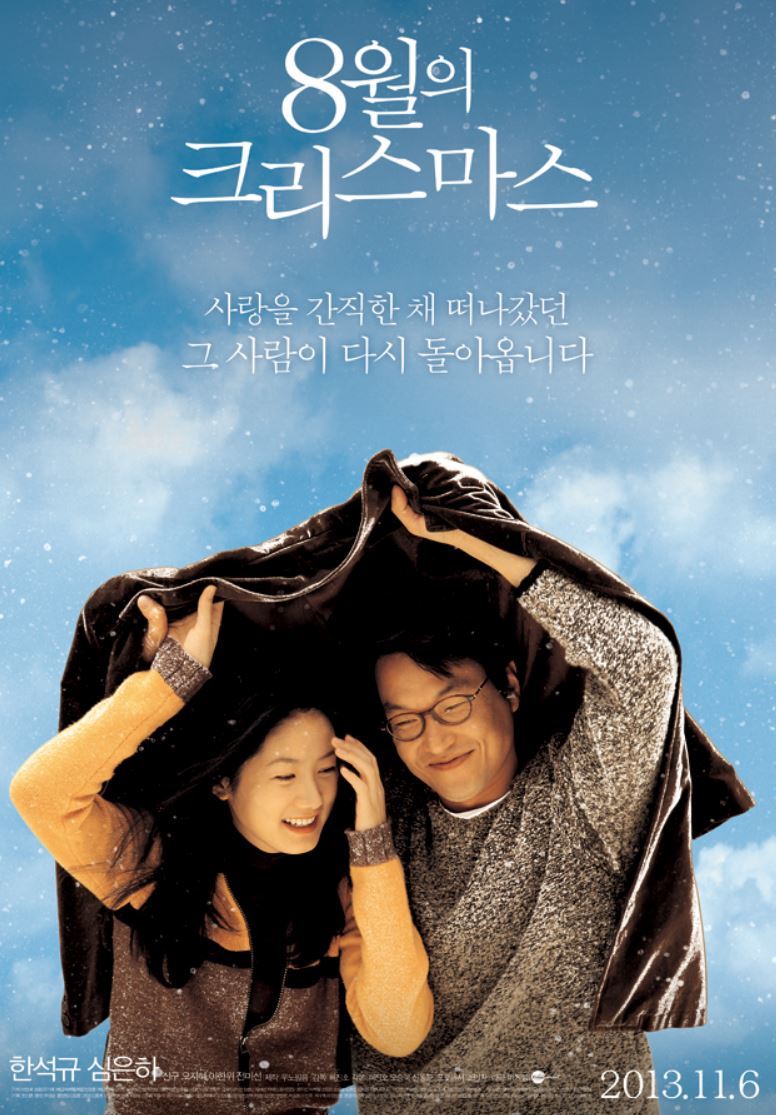

The cruel ironies of life are visited on a lovelorn photographer nearing the end of his days in Hur Jin-ho’s understated melodrama, Christmas in August (8월의 크리스마스, Palwolui Christmas). Christmas in August was Hur’s debut feature though he’d become primarily known for similar material in coming decades even if the romance was rarely as subtle and achingly poignant as in his first film. In some ways about life’s unfinished business, the impossibilities of communication, and coming to terms with impending death Hur allows his melancholy leads to discover a kind of serenity even in the depths of their yearning.

We never really find out the nature of Jung-woo’s (Han Suk-kyu) illness, only that it does not ostensibly interfere with his ability to live a normal life, though unfortunately terminal. After learning that he has only a short time to live, he simply goes home and washes the dishes, continuing with the mundanities of his life as if determined to get on with it. When someone asks him about his health, he tells them that he’s fine or that it’s not really serious, drunkenly letting slip to a friend that he will die soon but making it sound like a joke. Aside from a single moment of drunken railing against his fate, he accepts it with dignity and continues living quietly much as he always has while making preparations for after he’s gone, painstakingly writing down instructions for his father on how to use the TV remote and use the more modern printing facilities in his photography studio.

There is perhaps a certain irony in the fact that he’s a photographer which is after all about trapping a memory or a point in time and preserving it for an eternity. He himself cannot move on, apparently hung up on his first love who married another man only to return later seemingly unhappy and regretful though she only asks him to remove the photo of her from the display in front of his store as if the memory of her youthful self is too painful to bear. And then, a young traffic warden wanders in looking for an urgent enlargement. For Da-rim (Shim Eun-ha), despite her youth, everything seems to be last minute, making several visits to the shop with an order that must be completed as soon as possible before visiting with no order at all.

The relationship that arises between them is diffident and tender. It is also largely unspoken, Da-rim simply remarking on having a friend that can get them free tickets to an amusement park without exactly asking Jung-woo if he would like to accompany her. From his side, Jung-woo is passive, happy to be in her presence but also wary in knowing there is no possible future for them. He obviously cannot tell her that he’s ill or this brief respite from the futility of his life would disappear while she takes his diffidence as a lack of interest. It’s a love story that never quite gets started but is deeply felt all the same even its chasteness.

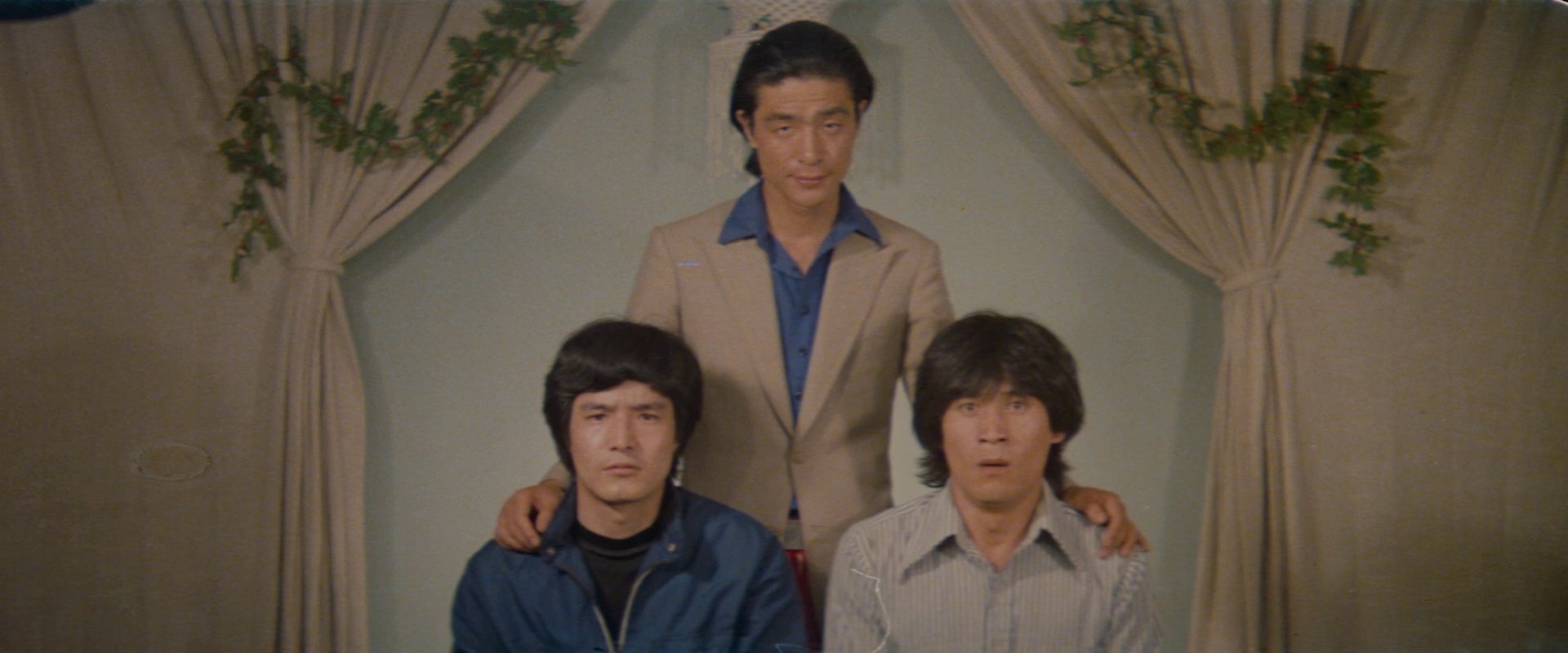

Then again, perhaps words are unnecessary in situations such as this, a single photograph explanation enough on its own. In essence a gentle character study of a dying man’s learning to part with life as mediated through his yearning for a young woman though knowing that his love cannot be fulfilled, Hur presents death as something warm to be accepted rather than feared. Jung-woo takes a final photo with his friends whose eyes are all moist with tears as they pull him to the centre though he, like always, meant to stand on the end. He simply continues living, doing the dishes, retouching photographs, drinking with friends or else quietly crying himself to sleep.

Though employing many of the tropes of romantic melodrama, Hur aims for subtlety and the eternal heartbreak of life’s unfairness that what we most desire arrives as soon as we can no longer have it. Even so, Jung-woo accepts his fate with good grace and treasures the memory of an unexpected love even as it slips away from him, storing it safely inside a photograph and a letter he may not actually intend to send. “Thank you and goodbye,” he signs off, which might be as a good a declaration of love as any other.

Original trailer (no subtitles)